Robotics Levels of Autonomy

Single-Purpose Robots Automating Hundreds Of Jobs, Pick And Place With Low Autonomy Is Expensive, General-Purpose Autonomy Navigating And Inspecting Large Sites, Targeting Low-Skill Labor In Early Pilots With Promise, Autonomy Capable Of Any Task In Resea

Robots have powered manufacturing for decades, yet they stayed single-purpose and thrived only in perfect settings. Previous attempts at intelligent machines overpromised and underdelivered. But they were too early. Today, modern AI paradigms convert most robot roadblocks into data problems and push machines toward capabilities once thought impossible. As these models absorb real-world experience, robots will sharpen current skills, gain new ones, and deploy faster, absorbing ever-increasing shares of labor.

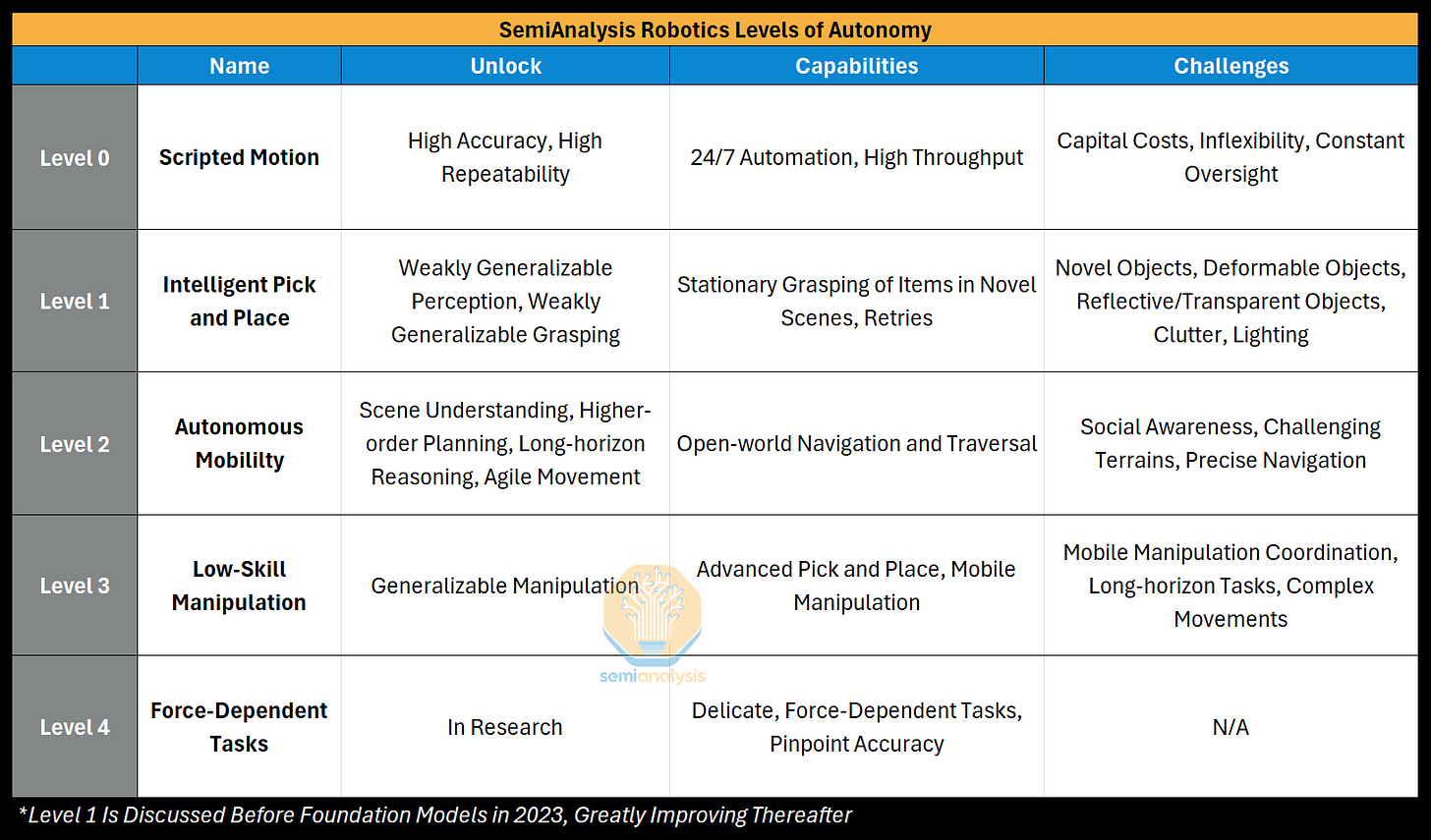

General-purpose robots that can accurately perform any task in any domain is now an inevitability, and mass labor replacement is on the horizon. However, these robots will arrive in levels, slowly adding more capabilities until all tasks are feasible. To provide a barometer for this progress, we introduce our industry-first “Robotics Levels of Autonomy,” which classifies robotics into 5 distinct Levels.

Each Level of Autonomy is defined by the capability unlocked, and each builds sequentially on those before it to enable new applications. To ground these Levels, we provide data-driven analysis of current deployments, use cases and economics, current challenges, and active areas of progress. The Levels provide a type of task segmentation in which progress is additive -- robots may target one Level of tasks and still benefit from capabilities developed in other Levels.

Our Levels of Autonomy are demarcated around commercial viability -- not merely what is possible. Robot autonomy is inherently linked to applications: creating value only through actions often irrecoverable. Therefore, capabilities are derived from reliability and capability. Once reliability is proven, the robot must deliver sufficient throughput to justify its cost as well.

Thank You

We’ve talked extensively to top scientists, surveyed numerous companies, traveled to top industry conferences, and dug into research surrounding contemporary robotics to develop this taxonomy.

We deeply appreciate the invaluable contribution of our coauthors: industry practitioners Niko Ciminelli, Joe Ryu, and Robert Ghilduta. We take inspiration from coauthor Joe Ryu’s framework to flesh out this classification. This project couldn’t be done without the help of outside experts.

We welcome feedback: Please reach out to discuss anything regarding our new Levels of Autonomy classification. You can meet us in person at most of the top industry events, such as Humanoids Summit SF, CoRL, Humanoids 2025 Seoul, and more.

Describing Autonomy

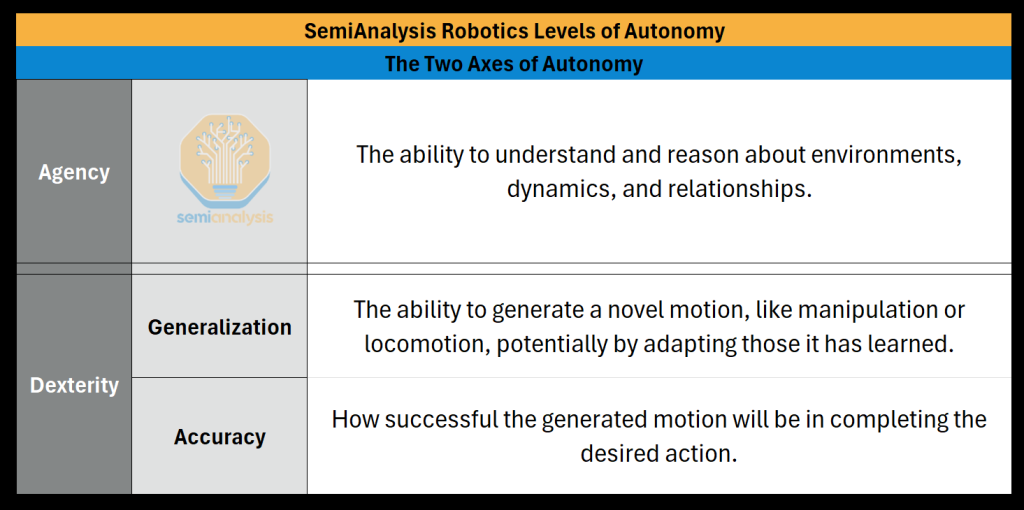

The path to full autonomy begins with accurate, single-purpose systems. But general-purpose robots must start anew, learning to see, plan, interact, and achieve exceptional accuracy. Along the way, their capabilities, applications, and challenges may vary widely. Each Level can be adequately explained across the two axes below, Agency and Dexterity:

By mapping gains along Agency and Dexterity, the framework shows what has been achieved, where the field now stands, and what to anticipate in the years ahead.

Currently, general-purpose robots are already working in early production phases in Level 2, but largely remain outside of the public eye. In Level 3, general-purpose robots are in early pilot stages of automating low-skill jobs and showing themselves to work. While we are early, this evolution will accelerate faster than most realize.

Executive Summary

Level 0: Scripted Motion - Robots are pre-programmed entirely, requiring static environments and tasks to function.

Unlock: High Accuracy, High Repeatability

Capabilities: 24/7 Automation, High Throughput

Deployment and Use Cases (2025): Industry standard in automotive and electronics factories

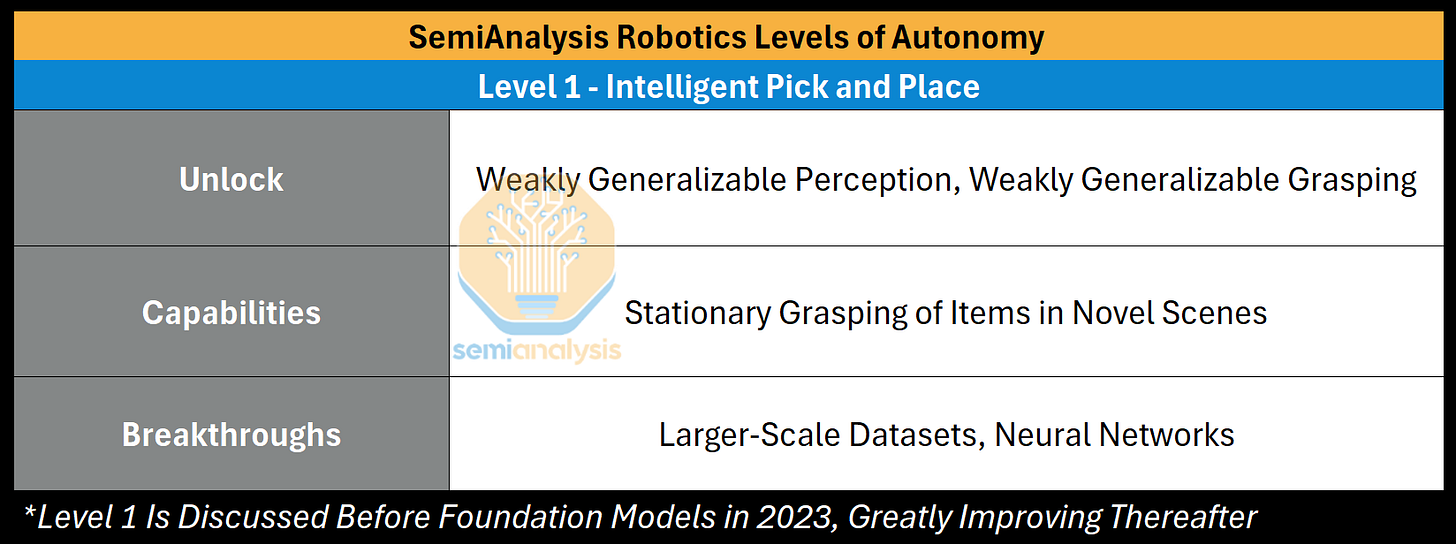

Level 1: Intelligent Pick and Place - Robots can identify items in various positions and pick them for sorting.

Unlock: Generalizable Perception, Generalizable Grasping

Capabilities: Stationary Pick and Place

Deployment and Use Cases (2025): Adopted in parcel logistics centers for pick and place sorting, increasing penetration in additional warehousing markets as capabilities and integrations improve

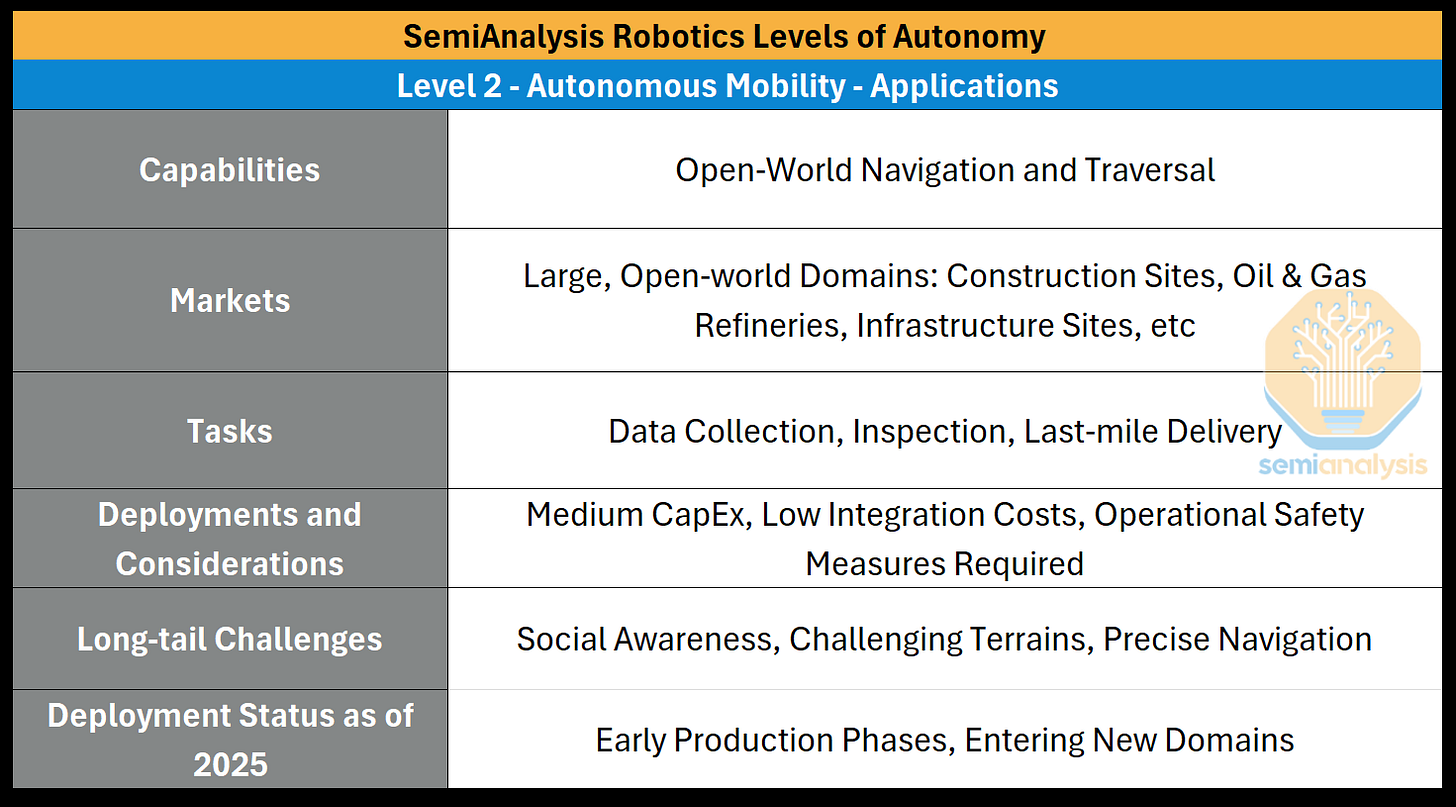

Level 2: Autonomous Mobility - Robots can understand the open world, navigate, and traverse various terrains.

Unlock: High-level Planning, Spatial Reasoning, Robust Locomotion

Capabilities: Open world Navigation and Traversal

Deployment and Use Cases (2025): Early production phases for inspection and data collection roles, e.g. construction sites, oil & gas refineries, critical infrastructure, etc

Level 3: Low-skill Manipulation - Robots can perform basic, noncritical, low-skill tasks.

Unlock: Generalizable Manipulation

Capabilities: Advanced Pick and Place, Mobile Manipulation

Deployment and Use Cases (2025): Early pilot stages in kitchens, laundromats, manufacturing, and logistics

Level 4: Force-dependent Tasks- Robots can perform delicate tasks that require force and weight understanding, e.g. finding a phone in a pocket, driving a screw on the correct threads, etc.

Unlock: In Research

Capabilities: Delicate, Force-dependent Tasks, Fine-grain Manipulation

Deployment and Use Cases (2025): In Research

Level 0 - Scripted Motion

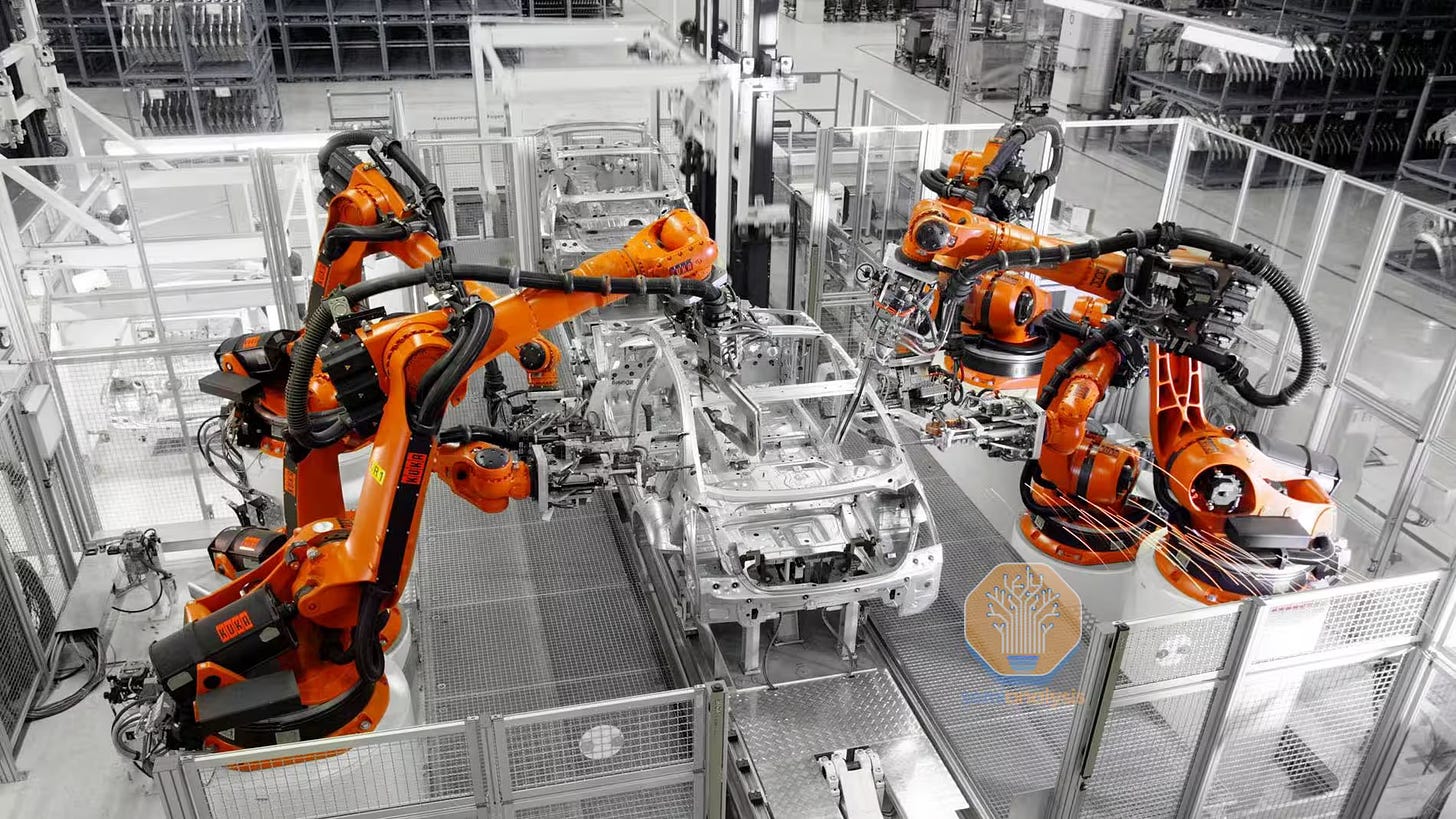

To understand the shift in robotics, we must first look from where it’s departing. When most think of robots, they picture Level 0: the automation that has dominated factories for decades, helping manufacture cars, electronics, planes, etc. The robots performing these tasks have incredible power, speed, and precision, but they operate with no intelligence, only via strict programming and perfect tasks/environments. Lacking entirely in autonomy, they are primarily monuments to industrial engineering and capital expenditure. They represent the rigid, single-purpose robotics world, and understanding their nature is paramount to seeing the monumental shift toward general-purpose robotics.

Current View

Deployments and Considerations: Locked Away

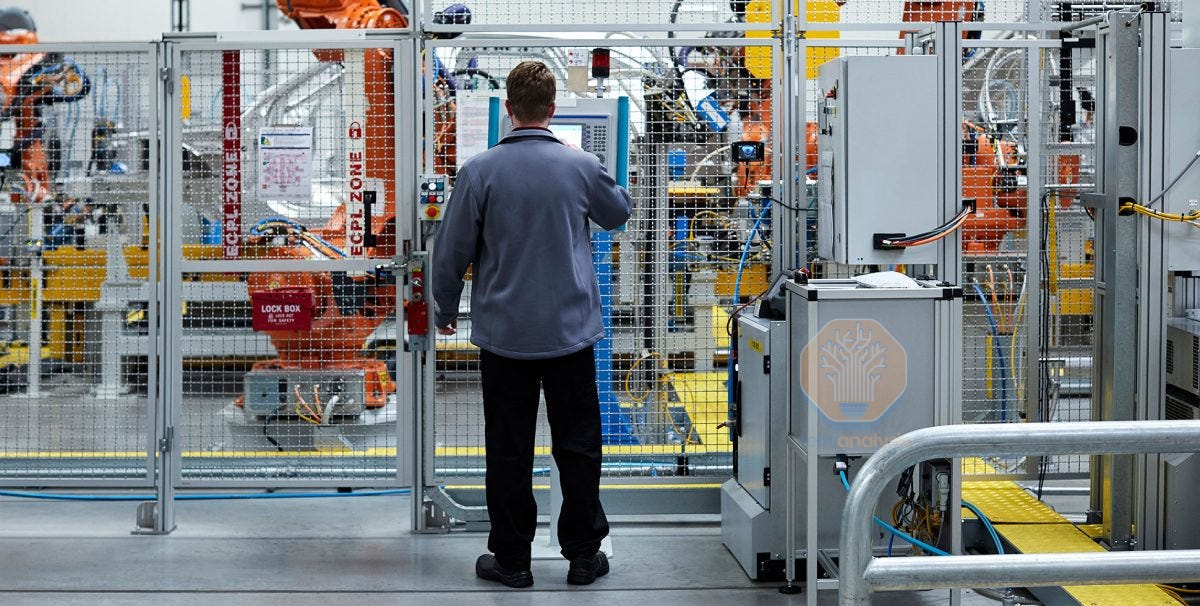

In Level 0, robots lack the ability to autonomously perceive and react to their environment, and the environment must be perfectly engineered for them. Everything is done on the robot’s terms, and everything and everyone else must comply.

This leads to the core of Level 0 deployments: the “cell.” The robot lives in a cage, fenced off for a number of reasons and with special designs:

Safety for the humans around the robot. These robots may be purpose-built for heavy lifting, making them extremely powerful. However, a lack of computer vision and autonomy means these robots will not adapt to a human in their environment, and will continue their action. Instead, the safeguards in place are typically Emergency-stop (Estop) buttons, light curtains, control barrier functions, but in a complex world, this may not be reliable enough for human safety

The cell isolates the robots to limit external interference or perturbations that can alter their environment, their positioning, or any aspect of the task at hand

Each cell is tailored to the robot and the location, making installation and programming of the task at hand simpler

This rigidity of Level 0 turns automation into an industrial engineering project. A new large-scale automotive assembly line can cost upwards of $10M-$60M and take years to build. An industry representative joked that these projects have “birthdays,” taking multiple years to complete. Retrofitting an existing factory is even harder, and for a unique system, the integration cost is extremely expensive.

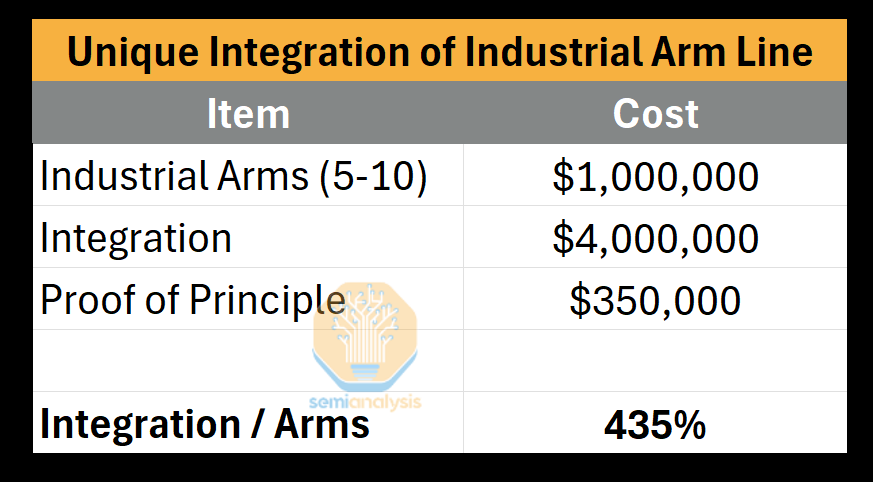

Integration: 4x to 6x The Cost of The Robots Themselves

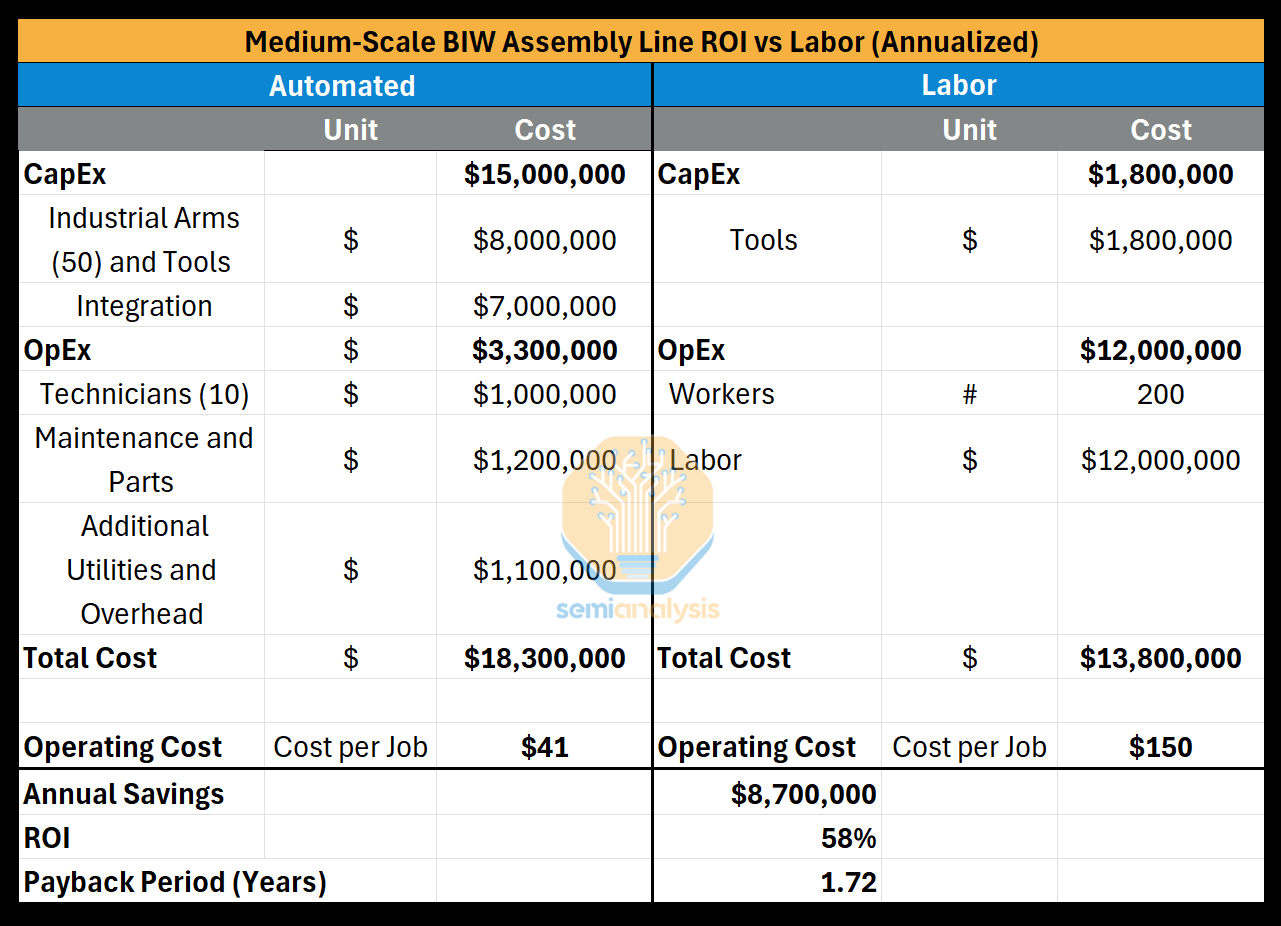

Because retrofit costs vary widely, let’s ground this in a concrete scenario of a medium-scale automotive facility retrofitted with a brand new, unique body-in-white assembly line--assembling the welded frame.

Typically, the same system integrator and robot brand+software will have to be used to ensure no chance of breaking the factory’s flow with new systems. The total integration can cost roughly 4x-6x the robots themselves in the end. Construction and deployment of cells, configuring related systems like (PLCs, conveyor/line tracks, MES, etc), and installation + testing racks up a big pricetag. A Proof of Principle (PoP), like a physical mockup of the line, can be built first to test out the system (which most should do), but most opt out of this unless it’s highly unique, like for pharmaceuticals. We remark that for standardized automotive solutions, this may run rather ~70% of the robot CapEx.

However, this immense cost and complexity is the reason automation has been historically confined to high-volume, low-mix industries like automotive and electronics. It is a tool for the capital-rich and often boxes out most medium-size or smaller facilities from implementing any amount of automation. General-purpose robotics, by contrast, aims to remove these barriers to entry in the later Levels.

Implications: Efficiency and Dark Factories

At Level 0, robots have become widespread additions to a few industries. Automotive factories often use between 400-1000 industrial robots per factory, some even reporting use of up to 1650. In electronics manufacturing robot usage is less, around 50-200 robots in a facility. These could be AMRs performing transport, SCARAs used for statically mounting parts onto circuit boards, CNC machines milling pieces of hardware, or cobots for machine tending.

The automotive line can pay for itself in under two years and afterward, operating costs are nearly ~75% cheaper. Industry representatives have said that after the payback period, these factories are “printing money.” Some facilities can even reach up to 2,000 cars per day, and warehouse arms can often do the work of ~10 people with no fatigue. The efficiency of robots executing Level 0 tasks warranted Amazon’s hundreds of thousands of robots. For example, 50 robots might perform the large assembly and manipulation work of 200 laborers at ~73% lower costs per job.

The pinnacle of this paradigm is the “Dark Factory,” a facility run entirely by robots without the need for lights. A representative from FANUC says there’s a factory in Japan where their robots are building one robot every 80 seconds. While this is the apex of industrial automation, it is still categorized as Level 0. The robots are entirely pre-programmed, the environment/task is perfectly sterile and controlled, and bears no resemblance to the dynamic, non-engineered environments of human labor. Instead, the task and environment are perfectly crafted for these robots to perform, maintain themselves, swap their own tools, and schedule downtime ahead of time for a human to come in and repair an issue.

Current Challenges: The Issue of Rigidity

The fundamental difficulty of Level 0 is the robot’s total lack of Autonomy. The robot cannot diagnose or solve a problem on its own, and this creates a host of issues down the line:

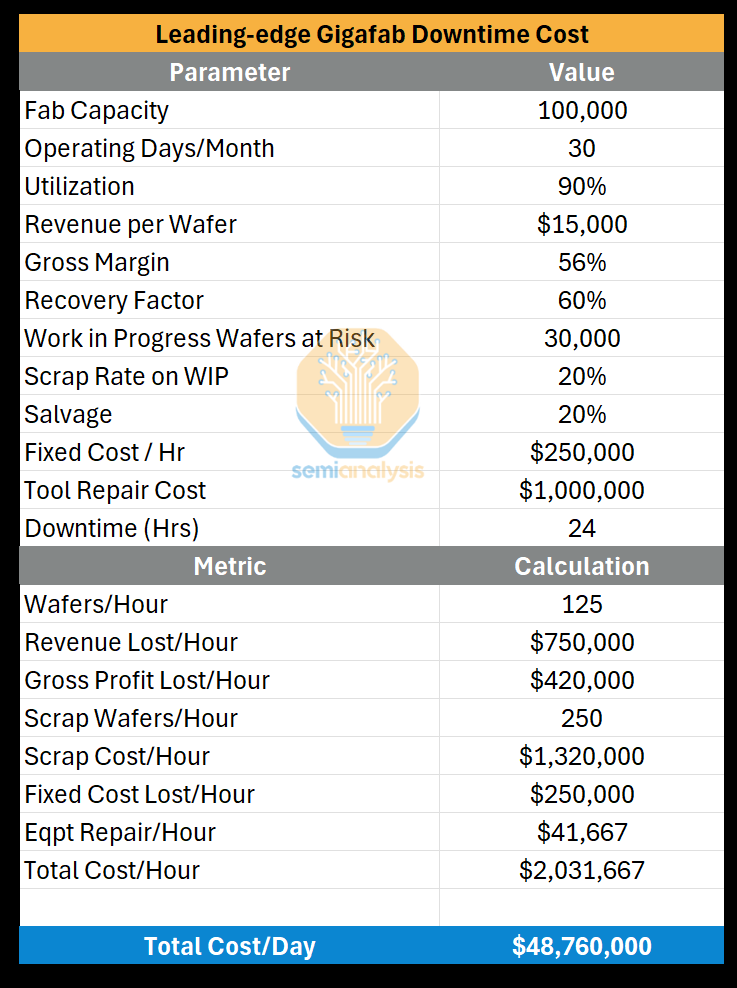

Constant Oversight: Human technicians must always be on-site (except in dark factories). Ratios may range from 20:1 robots:humans, and down toward 12-15:1 for demanding industrial settings. Most of the time, when humans take a lunch break or swap shifts, the robots have to be stopped as well. If these robots fail, downtime can be incredibly costly, like $2M per hour in automotive, or $50M/day in semiconductor fabs.

Capital Incineration: A small error in programming, poor integration, or failure of two systems to sync can render an entire multi-million dollar factory non-functional. The factory now turns into an industrial engineering project, and this risk is too high for smaller companies, cutting them out of the automation market

Inflexibility: Amazon, a powerhouse of industrial engineering, has to build their fulfillment centers around these non-autonomous robots. In fact, instead of making the robots more collaborative/intelligent, they found it easier to change the workers by designing a special safety vest, slowing the robots when the worker was nearby.

Looking Forward

Promising Sources of Progress

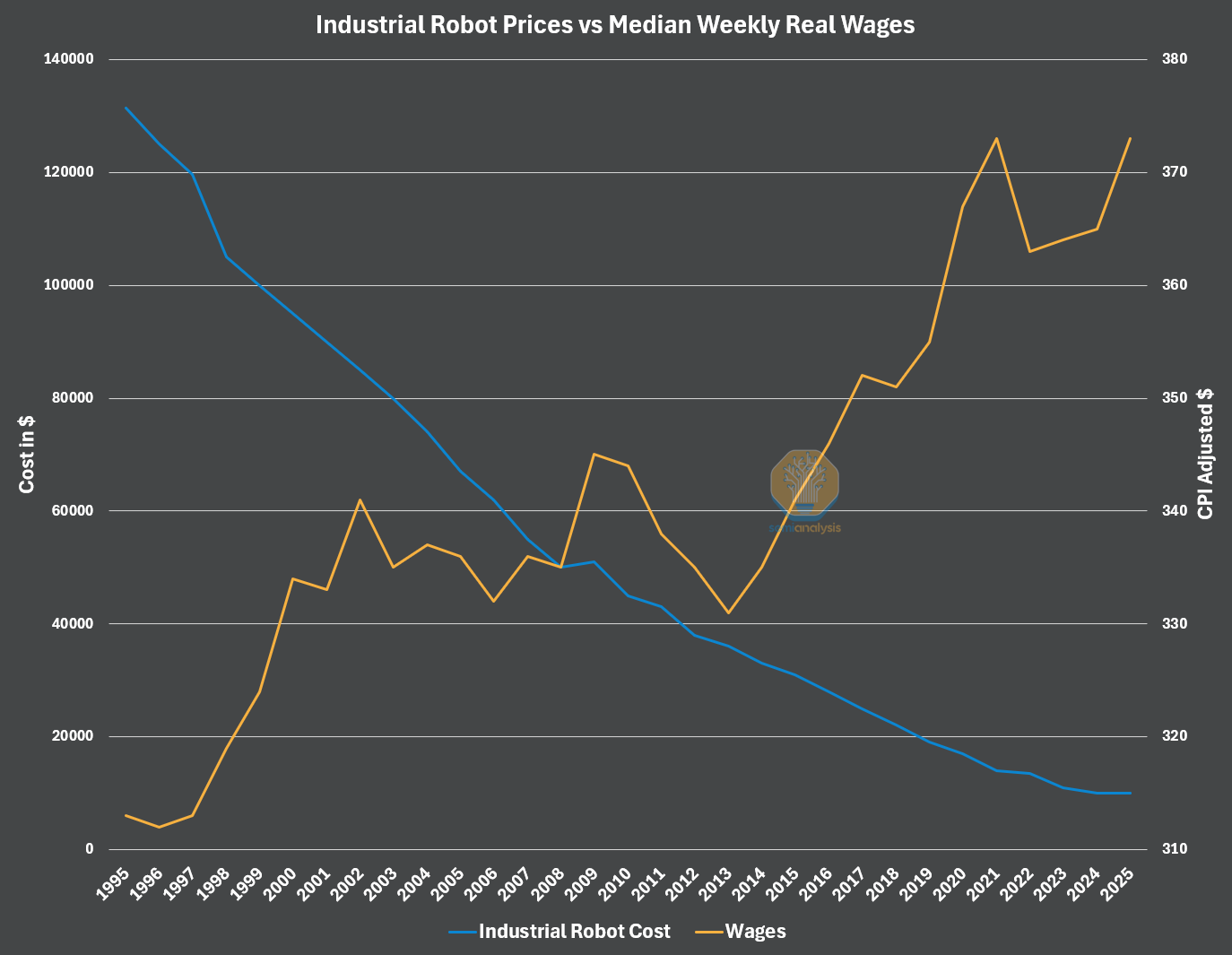

For Level 0, we see costs decreasing as a significant path forward. As real wages climb and industrial robots’ prices drop, they become even more attractive. This should continue over time. Robotics being a manufactured good means that as manufacturing processes improve, production increases, and economies of scale take over, the robots should become more cost-efficient.

This would lower the barriers to entry for a much wider market, enabling a broader adoption of robots performing Level 0 tasks without requiring industrial engineering prowess or massive CapEx.

Additionally, most provide an equipment monitoring system, like FANUC’s Zero Downtime solution. These enable the robots to predict their failures ahead of time, reducing the need for constant oversight and bolstering dark factory potential. While substantial, they are fairly new, and constantly improving themselves.

Finally, integration of these robots might be streamlined through a more “unified” industrial software. Instead of deploying only one brand of robot, system integrators could then plug-and-play multiple brands/setups, creating less finicky automation systems faster and cheaper.

While these would improve scripted motion systems, the challenge lies in their perfected applications. These robots only function in static, engineered worlds, but genuine labor replacement requires adaptivity and autonomy. As Level 1 will highlight, perceiving a changing task and adapting was not as simple as it sounds.

Level 1: Intelligent Pick and Place

In Level 1, robots can now see. Around 2015, we saw the first injection of intelligence into robotics, creating a new Level of Autonomy that would later attempt commercialization around 2018. In this Level we will focus on the era from 2015-2022, before foundation models arrived.

Robots first broke away from Level 0’s static tasks when they shifted into "pick and place," picking an item from area A and placing it in area B. Pick and place lives in a non-perfect domain where objects, configurations, and lighting may all change. The robot must generalize its perception to determine the object and its pose, and tweak its grasp accordingly-- a task impossible for Level 0 robots. Large-scale datasets, and smaller but vital grasping datasets, powered this attempt into Level 1 autonomy by unlocking a piece of Dexterity: Generalization, especially in perception. With enough data, the robot could recognize objects, sometimes novel, in various poses and angle its grasp for picking.

The commercialization attempts went toward warehouse and logistics “pick and place” roles, slotting robots near sorting lines to organize non-delicate items by picking the object from bin A and placing it in bin B. However, this first attempt at intelligent robots was bottlenecked by insufficient data, nascent AI models, demanding throughputs, and high costs, all leading to unproven ROIs. During the years of 2015-2022, a few companies built “arm farms,” performing months of grasps to accrue enough data for training. Pick success eventually rose to 99% percent, but the “last millimeter” to 99.99% percent was almost as difficult, and even this sometimes wasn’t enough to prove ROI. Level 1 saw a valiant first step, and consistently displayed linear improvement over time, but this ultimately highlighted how many challenges remained in robot autonomy.

Nowadays, some companies have continued to reap the benefits of linear improvement, and advancements in AI models and deployment solutions have created a new viability for robots targeting Level 1’s pick and place. These robots are currently ironing out their remaining Challenges to become more capable than the original attempts.

A Look at The Past - 2015-2022

Adapting to Novelty

While pick and place is simple for humans, the non-static nature was a massive hurdle for a robot. Items, sometimes novel, can arrive jumbled, occluded, or presented in new ways. Each of these variables, along with challenges like shadows, reflections, or transparent objects, could cause the robot’s early perception systems to falter. They might misidentify an item, misjudge its position and shape, and ultimately fail the grasp altogether. This was a level of chaos beyond Level 0. What was missing?

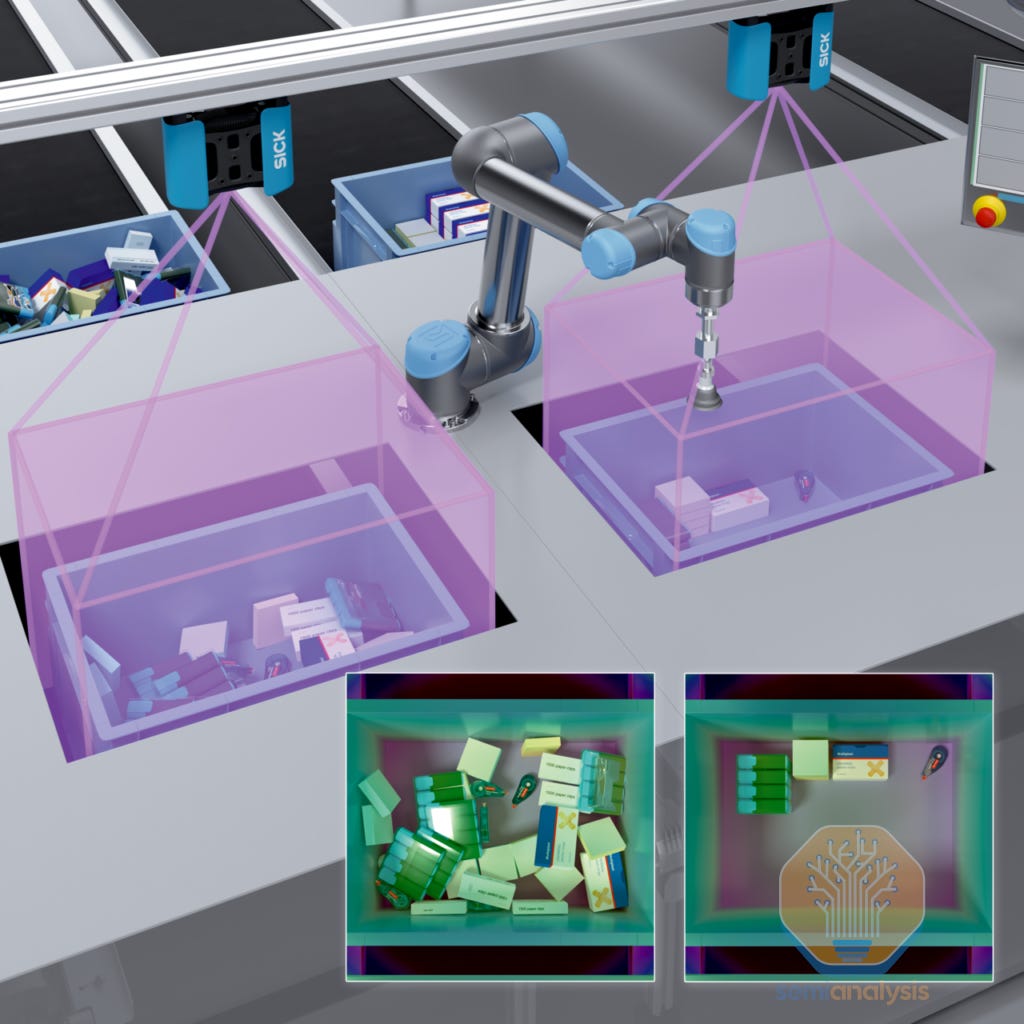

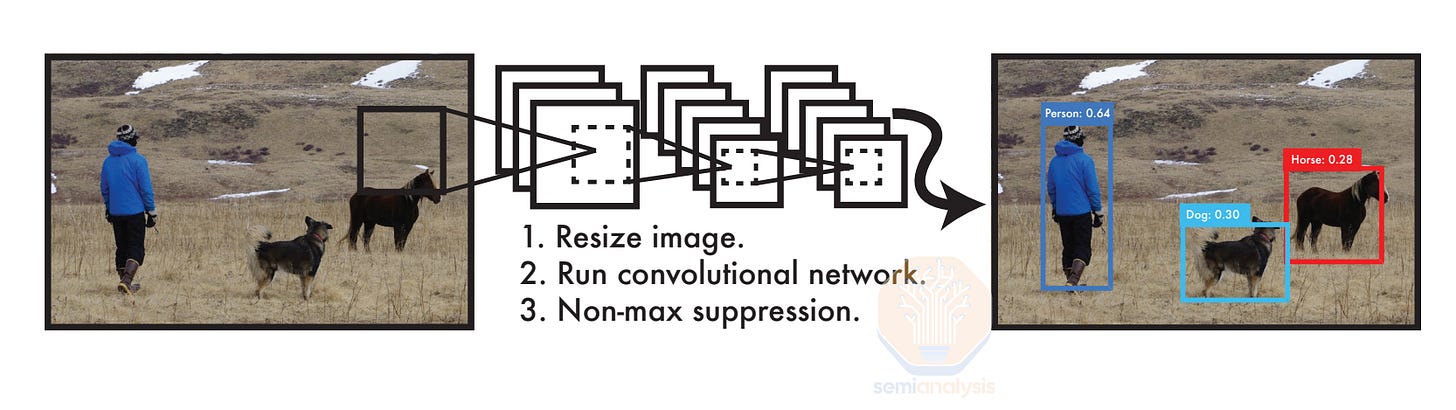

Problem 1: Seeing and Understanding - Before Level 1, cameras on robots were mainly to verify that an action and task had been completed. However, autonomously picking an object from a cluttered bin requires generalizable perception --perception capable of adapting across novel scenarios. In Level 1’s pick and place, this is identifying an item, discerning it from the clutter, and estimating its shape and pose. Broad visual reasoning like this could come from today’s Vision-Language-Models (VLMs), but this 2015-2022 era mainly used neural networks that needed large, annotated datasets of application-specific images that didn’t quite exist for robotics applications.

Problem 2: Learning to Grasp - After identifying the item, the robot needs to grasp it without picking its neighbors too. This demands grasping that can generalize to new situations each time, but learning this requires masses of trial and error data. In 2015-2022, open-source communities and crowdsourced data were not as large as today, so data collection came from real-world, expensive robots repeatedly attempting slow grasps. Simulators, where robots can act and gather data in a virtual setting, were not sufficiently robust at the time to replace physical data. They suffered from what’s called the "sim2real" gap, in which physics, environments, and actions in simulation didn't match reality. The sim2real gap was significantly more challenging in this era, and still isn’t solved today.

Beginning Sparks

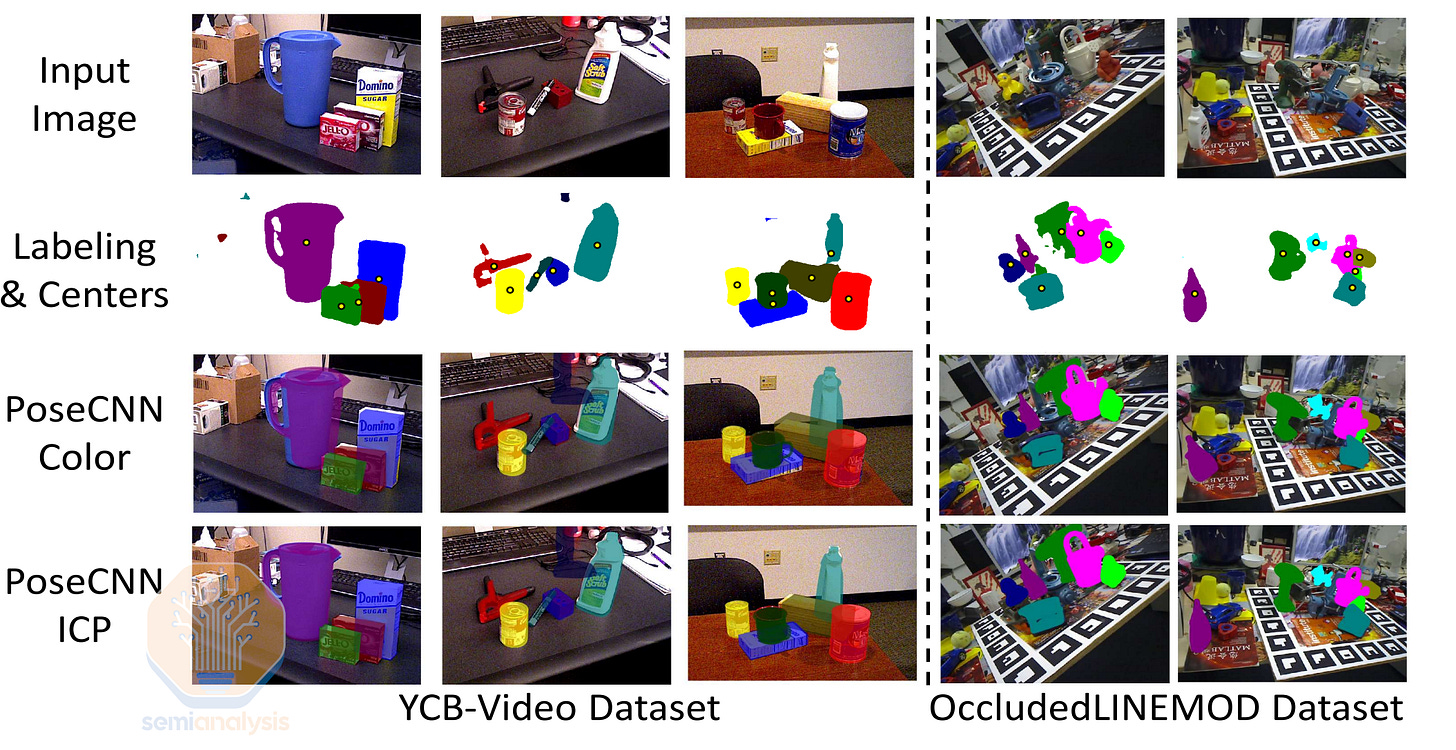

The first signs of a solution to these two problems came from the computer vision world, enabling generalizable perception. The creation of the large-scale ImageNet dataset (2009) and the success of neural networks like AlexNet (2012) showcased the potential for computer vision. This then sparked many new projects, like YOLOv1 (2015), which allowed for real-time object and bounding box detection for locating objects, Mask R-CNN (2017) then enabled shape estimations with “masks” to segment objects from the rest, and finally PoseCNN (2018), which tied it together with 6D pose estimation of objects with just a stereo camera. With these efforts, models had early generalizable perception, capable of understanding multiple objects in multiple contexts for the first time.

While perception was finally generalizable, it was still brittle. Systems were still easily confused by novel objects, reflective or transparent objects, shadows, or too much clutter. However, in this era of 2015-2022, many saw these advances as a chance to support perception in robotics; maybe the robot could now generalize perception to identify the object and its pose for picking.

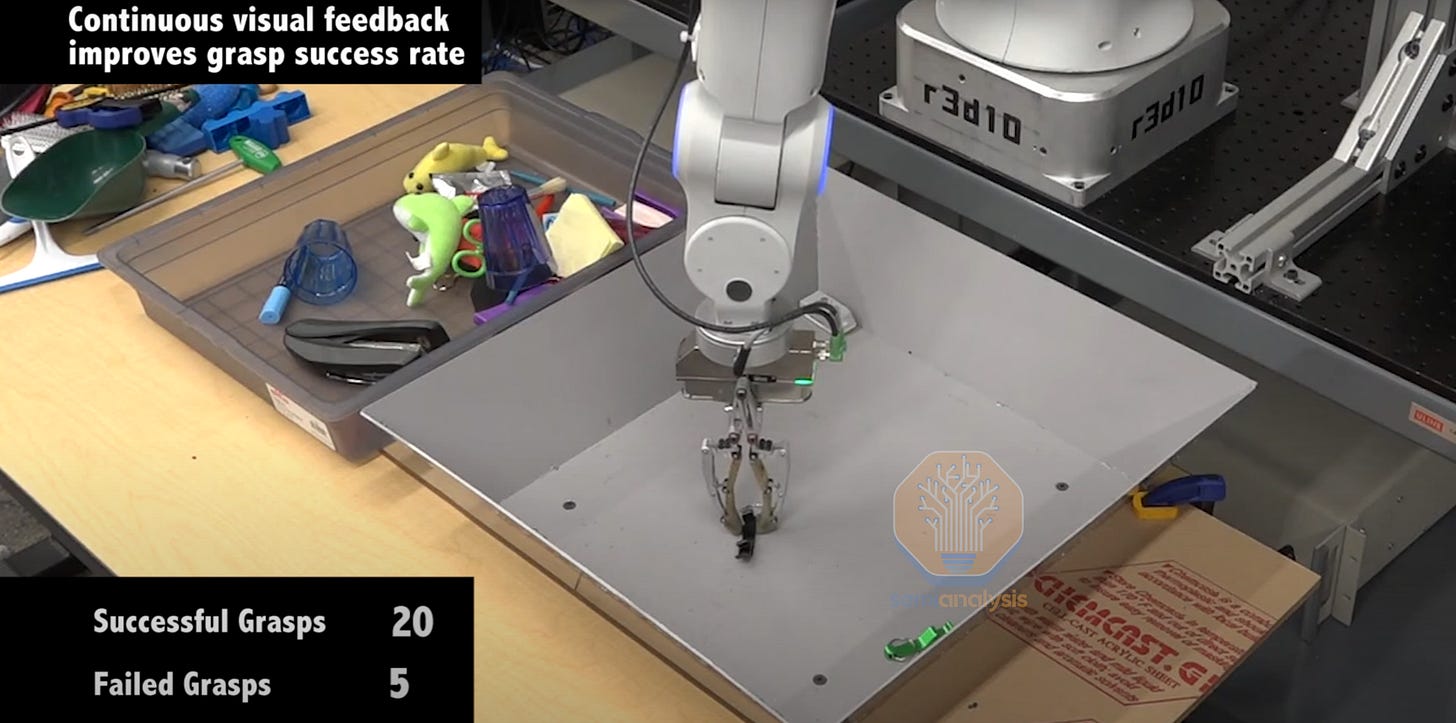

This breakthrough in perceptual abilities fired up researchers to attempt amassing robotic grasping datasets, where some like Pinto & Gupta (2015) showed 700 hours of robotic grasping attempts enabled their robot to reach 80% grasp accuracy.

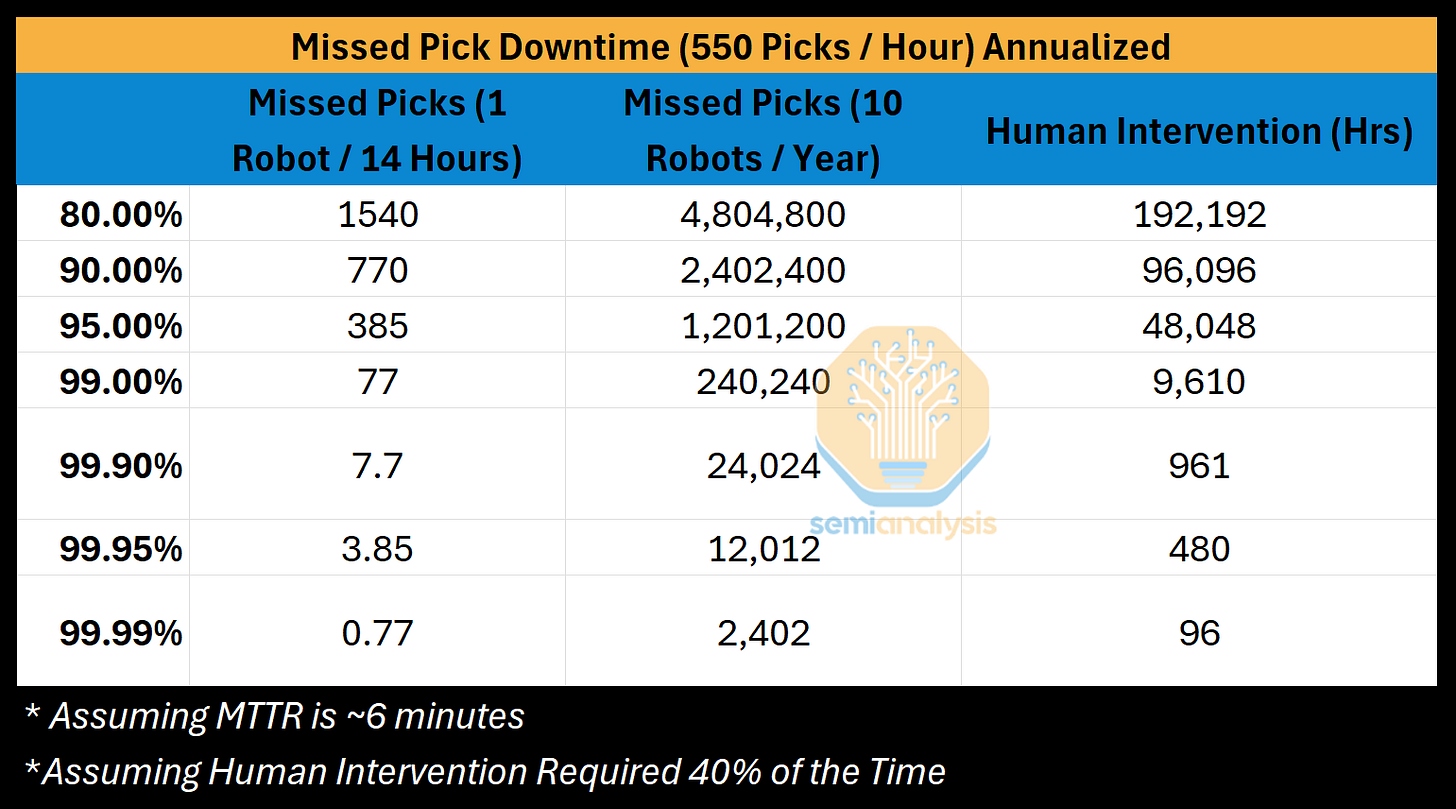

While this “adaptive grasping” was monumental for robotics, 80% does not meet the threshold for most commercial applications. Each failed pick typically couldn’t be resolved by the robot due to its lack of autonomy, and 40% of the time required human intervention. Since these were often unsafe industrial arms, the human had to pause the whole warehouse line, solve the issue, and resume the process, leading to an average Mean Time to Recovery of ~6 minutes.

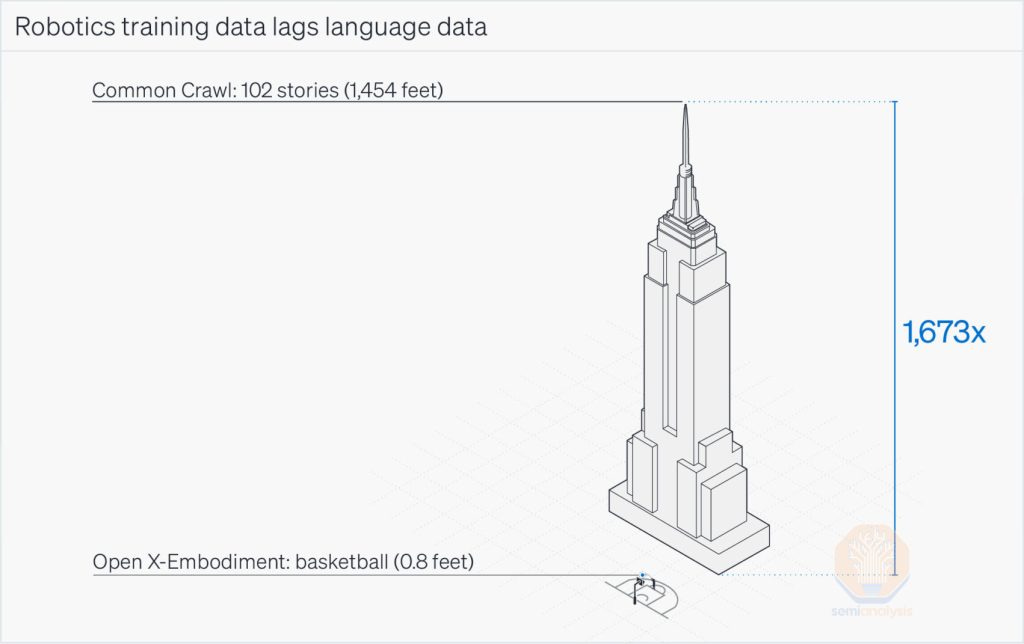

More projects came out after scaling data showed promise in robot learning, like Levine et al. (2016) who released approximately 3000 hours of grasping data and achieved 94.6% grasp prediction accuracy after fine-tuning. However, the large-scale datasets were mainly coming from the computer vision side, and robotics was left with much less grasping data to work with.

Even with the modern booms in robot data, the field is still tiny, and data was substantially less during this era.

In the end, some companies decided the best approach to learning grasping was generating massive data themselves via arm farms. They did gather huge datasets over several months, but often 99% success rates weren't enough. Worse, the jump to 99.99% is an 81x improvement, larger than the initial 1%-80%. Some were able to reach even this, but it became a Sisyphean task as each novel item and botched grasp set the percentage back. However, their challenging integrations and low autonomy ultimately bottlenecked many companies the most, and still pose an issue today.

Deployments and Considerations: The Wild West

During the 2015-2022 era, integrating these AI robots into the optimized, unforgiving warehouse environment -- where 98%-99% of the deliveries are on time -- became a “Wild West” of hazy estimates and improvised solutions. Unlike a Level 0 project, the challenges for these pick and place robots are not only physical but also informational.

Integration of these arms and cells into a warehouse line might cost $90K-$180K. But the robot also had a new custom API that had to complete a “handshake” with the facility’s Warehouse Management System (WMS) which coordinates all inventory and logistics. Oftentimes, the robot’s API was not built with a WMS in mind. As a result, the WMS had to update to accommodate this handshake gap, and a failed WMS update can cost tens of millions of dollars. As a workaround solution, a third party integrator might be used and charge up to hundreds of thousands for deployment. Most of the time stop-gap fixes were used to sync the systems instead, like GUI automation agents, a program that merely emulates a human clicking the right buttons.

Because the robots needed a full cell installation, integrators chose ideal, cheaper spots, such as a pick and place station between two horizontal conveyors. Difficult locations, like the vertical putwalls, were skipped, because most robots learned in horizontal applications, and reconfiguring the line to horizontal was costly. By screening proper locations, installations might only take up to 4 weeks.

Even then, the warehouse’s decision cycles to implement these robots might take months, and some clients would end up choosing to install the robots only in their own isolated area, away from the opportunity of breaking the warehouse’s process flow.

Nonetheless, the autonomy of these robots was still too low. Employees often weren’t “replaced,” but reorganized around the robots. They typically performed the pre/post-processing of the line of the robot, or became robot technicians.

Implications: A Narrow Market of Profitability

The promise of Level 1 was enormous: the automation of low-skill, high-turnover pick-and-place jobs-- a new market for the robots. The task’s basic nature made it seem like a good fit for a robot that could do just that: Pick and place. Businesses had large incentives for automation, as wages were packed with “loaded costs.” For example, we’ve heard Amazon sees a turnover rate of 2%-4% per week. This means that for every 100 workers on the floor, by year’s end 104 workers may have quit. Thus having to constantly hire, onboard, train, and ramp up productivity renders the wage 56% higher than with no attrition in the workforce. In fact, Amazon currently has a crisis of having already cycled through every low-wage worker in some regions.

Not only is the cost enormous, but the logistics of constantly hiring new employees are burdensome, and many hiring waves may result in most quitting within the first week. These challenges and costs made the role ripe for an AI-driven robot as a viable, consistent labor replacement. However, many found that the business case was highly dependent on the specifics of the task.

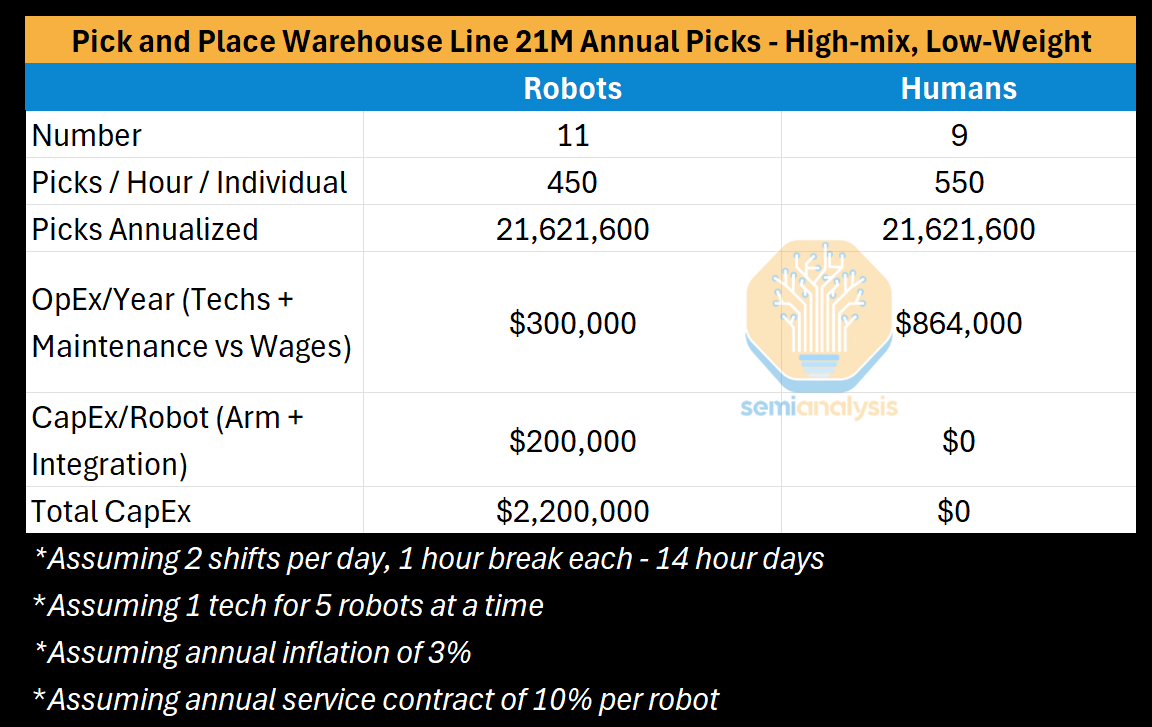

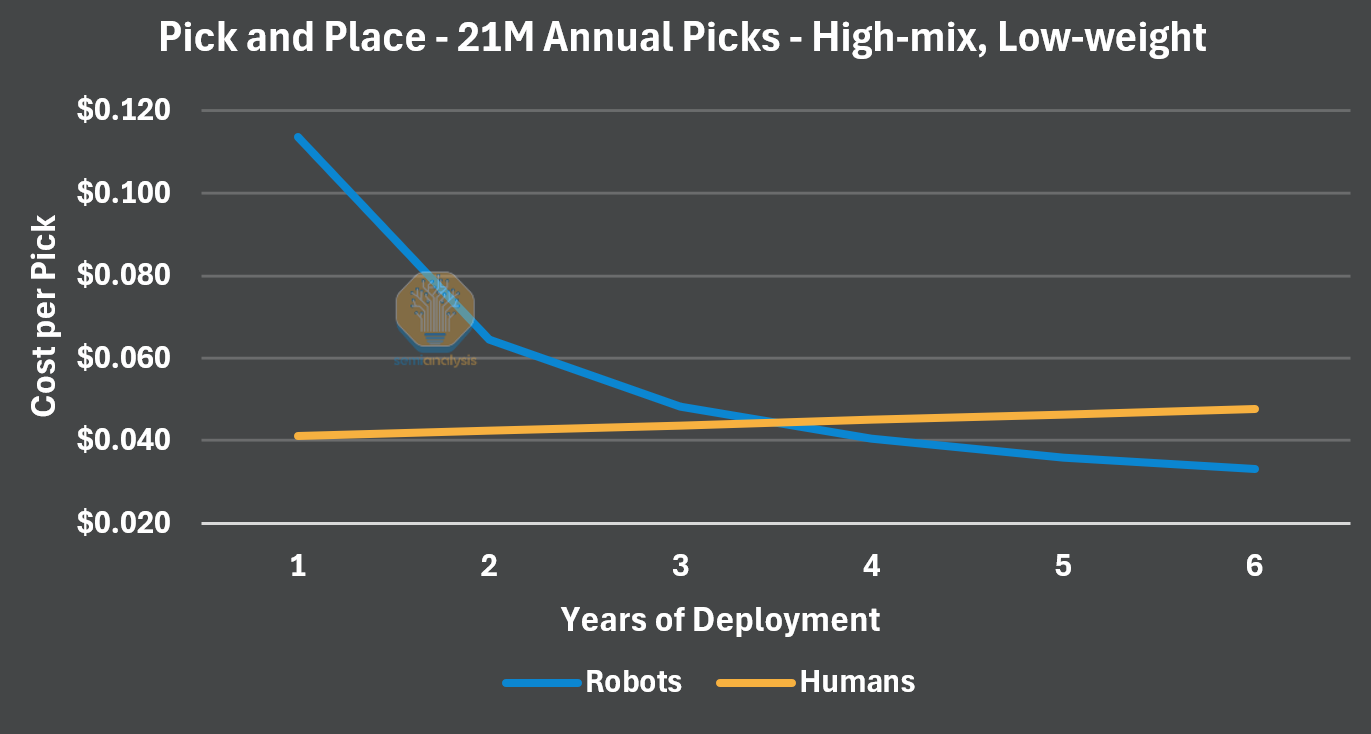

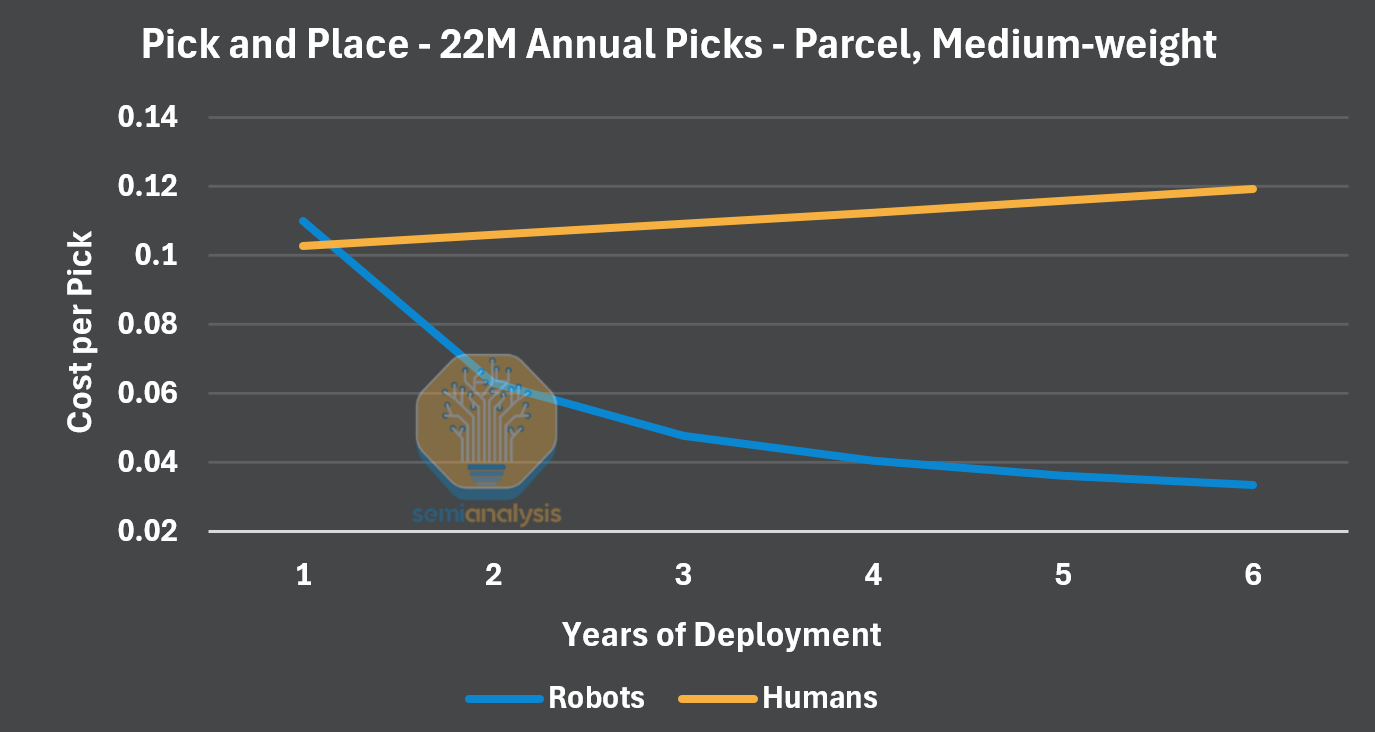

Consider a high-mix, low-throughput task like e-commerce fulfillment, where a robot must pick a wide variety of items at a modest pace.

Dividing cumulative picks by cumulative cost, we show below how cost per pick evolves over time. In the e-commerce case, the cost per pick of the robot doesn’t drop below a human’s for 3.5 years, and their effective pick-rate remains below a human's, with 11 robots doing the work of 9 humans.

E-commerce-like warehouse lines posed an interesting challenge for our intelligent pick and place robots: matching a human accurately picking multiple items. While a human may pick 5 items at once, these robots would likely pick one at a time, falling short of human throughput. Then, if the robot could pick fast enough, the surrounding conveyor and pre/post-processing systems would be locked at certain speeds, or clogged by the humans on either end, limiting throughput again. The warehouse could potentially make up for this by installing more robots, but the cost grows prohibitively. Worse, the “high-mix” of items is likely to bring too novel of an object/scene to grasp successfully, so many had to reach 99%+ to mitigate the six minute downtimes. All in all, this configuration of specifics made it difficult to justify the cost of intelligent pick and place robots.

However, Level 1 introduced a new upgrade: retries. If the task fails, the robot can detect the error and retry (a few times), whereas errors in Level 0 would freeze the process flow immediately. Let’s take for example “parcel” pick and place, where items arrive in parcels - uniform boxes and packages with labels.

Parcel pick and place benefits intelligent pick and place robots two-fold: the packages can be heavy, fatiguing humans for lower throughput benchmarks, and they’re fairly uniform, so failed picks can be retried and resolved easier since it’s likely not a generalization error as it was in ecommerce.

The robot can target 550 picks/hour, but even 95% accuracy in this domain delivers an effective pick-rate of 520.

In this case, we see 10 robots doing the work of 23 human workers. In these conditions, the robot cost per pick drops below human rates just after one year.

The robots targeting Level 1’s pick and place found a niche, but only in very specific domains of pick and place. While it’s easy to look back and understand what worked and what didn’t, this was new at the time. We’ve asked some companies why they didn’t target parcel domains to begin with, one paraphrased answer exemplifies the era: we didn’t know, we realized too late. This was the first foray into intelligent robotics, and while parcel is a smaller market than ecommerce, autonomy was simply too early.

Challenges: The Limits of Brittle Intelligence

For this pre-2023 time period, perception struggled. Some tried to skirt the fragile perception by replicating their deployment sites in their lab’s arm farms, following the same catalog of items the robot would pick, and even deploying with specific, static lighting fixtures. Most of these guardrails only partially resolved the shortcomings. Instead, 25% of Amazon’s item catalog is on the “exclusion list,” a list of objects not to be picked by the robot for risk of failure.

The Dexterity in this era was still nascent. If the company introduced a new item, they would test-run it with the robot, and if the pick fails 5-10 times, it’s placed on the same exclusion list instead. Additionally, without robust generalization the robot could pick multiple items at once, messing up the warehouse flow again. The generalization available at the time simply was not robust enough.

While other tasks seem relatively simple and a mere variation of pick and place, they can introduce different challenges. Take for example folding a shirt, which might seem like an easy task for a robot. In reality, objects like shirts are deformable and “high-dimensional.” The robot’s neural network would begin by cataloguing every wrinkle, crease, fold, etc on the shirt to understand it. This is called the “state explosion” problem, and it’s specifically difficult for Reinforcement learning in which the model tries to verify steps in the process as good or bad decisions, as now there can be an incredible amount of combinations. In Level 1, folding clothes became the “holy grail” for the era.

The Present Moment and Looking Forward

Promising Sources of Progress

The pre-2023 era was plagued with shortcomings, leaving many industry professionals battle-scarred. However, the companies of today targeting Level 1’s pick and place have created viable solutions, patching many challenges and refining their systems. Some are implementing end-to-end solutions to resolve unpickable items, lowering failure rates, recovery times, and mitigating the exclusion list downside. Modular systems can now skirt physical integrations and offer much higher throughputs, albeit at a higher cost. In-house operating systems now allow for streamlined, cheaper WMS integrations. Even simulators have stepped up enough to bootstrap basic parcel pick and place data.

But importantly, many robots are utilizing Foundation Models for deep, generalizable perception and spatial reasoning. We explore what foundation models provide for robots in Level 2.

Level 2 - Autonomous Mobility

In Level 2, robots gain general-purpose autonomy. They are now capable of planning their own tasks and traversing the open world autonomously. This capability was not feasible before, older models would be left confused due to the open world’s ever-changing scenes, terrains, and objects; rigid movement approaches would fall short in this chaos.

Instead, for Level 2, robots get Agency, gaining higher order planning and spatial reasoning from recent advancements in foundation models and Vision-Language Models (VLMs). Additionally, robots now have the Dexterity to traverse difficult terrains thanks to large scale reinforcement learning in simulation. This Dexterity in locomotion enables the robot to exhibit agility in its movements. Both approaches leverage massive digital datasets for learning, rather than collecting data on each scenario, mitigating the data scarcity challenges. In Level 2, robots autonomously perceive and understand their surroundings, plan a path, and use their robust locomotion to maneuver around the open-world on long time horizons.

The general-purpose robots of Level 2 are currently being deployed in early production phases for data collection and inspection roles in massive domains like construction sites, oil & gas refineries, and infrastructure sites. These sites are often too large to be effectively covered by humans, too large to be sensorized cheaply, too dangerous for humans, or too remote for cheap inspections by humans. Instead, these robots equipped with additional sensors can use their autonomy to plan and execute these roles.

These autonomous robots are the first proof of the general-purpose revolution. This leap into Agency reverberates throughout subsequent Levels, serving as the genesis for general-purpose robotics.

Current View

Entering the Open World and Agency

The central challenge of autonomous mobility is the open world, an environment with no rigid structure or predictability. Unlike the engineered environments for Levels 0-1, the open world is a chaotic collection of ever-changing scenes, obstacles, terrains, and weather. To operate here, a robot must surpass simple perception and classical, rigid planning toward scene understanding and higher order planning. However, early algorithms were not sufficiently robust to rise to the task.

Where am I? - Positioning Within An Environment

The open world does not always provide a static path, and the robot must determine where its own position is in relation to the environment, otherwise it may get lost. This requires constant map updates, and small position errors in the updates compound over time, turning inches of error into feet and leaving the robot confused. This error could be the difference between a fully charged robot and a dead machine on the floor. Advanced players might solve this without extra measures, but most might still use AprilTags, QR code like stickers for robotic reorientation and calibration, placed at the charging station. These can set fixed, pre-programmed paths or behaviors for which to guide the robot.

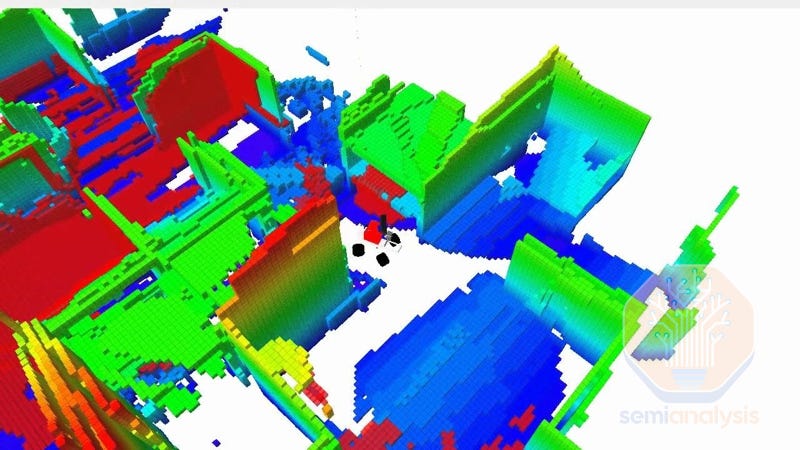

First Solution: SLAM - The main engineering solution to this is Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM). Using sensors and data, like LiDARs, velocity, time, etc, the SLAM algorithm allows the robot to build a “map” of its surroundings while simultaneously keeping track of its own location within the map. However, SLAM is still limited to geometric representations. Open-world environments are constantly shifting and demand a more “cognitive” understanding to lessen this drift or error potential. SLAM may not be substantial on its own, but rather a complement.

Planning, Reasoning, and Scene Understanding

A robot may know its positioning, but it may still not know what to do or what’s around it unless explicitly programmed. To navigate a chaotic environment, the robot would need a more foundational understanding of its world. For example, a robot might need to both distinguish a black puddle from asphalt, and plan its next moves. A failure in perception might lead to mistaking the puddle as not a hazard. Or, a failure in planning might lead to the robot dodging the puddle at the wrong time.

The Breakthrough: Foundation Models

Recent foundation models give robots the missing pieces for reasoning and long-horizon planning. By training on an internet-scale text dataset, a robot no longer needs every situation laid out in code or explicitly learned via expensive, scarce real-world data; it can instead generalize a massive knowledge base to new contexts. These models can translate situations into step-by-step, natural language descriptions it can reason through, unlocking far broader capabilities.

Vision-Language Models (VLMs), a type of foundation model, can bridge the language and visual modalities, enabling visual reasoning and problem solving. These foundation models are trained on massive, internet-scale datasets of images, captions, and descriptions, and fine-tuned on robot-specific data to allow for better spatial reasoning. Now, robots can broadly generalize perception, mitigating the lack of robot perception data from before.

All of this constitutes the robot’s newfound Agency: generalizable planning, reasoning, and perception. The robot can now obey and follow instructions in many novel environments. For example, in the command "go to the stairs past the ladder," the VLM would identify objects and their relationships, then translate the scene to the foundation model for the plan "move left of the ladder, then right toward the stairs." This loop of “thinking” grants the robot the autonomy to perceive and navigate the open world on long time horizons

Agile Movement - Dexterity

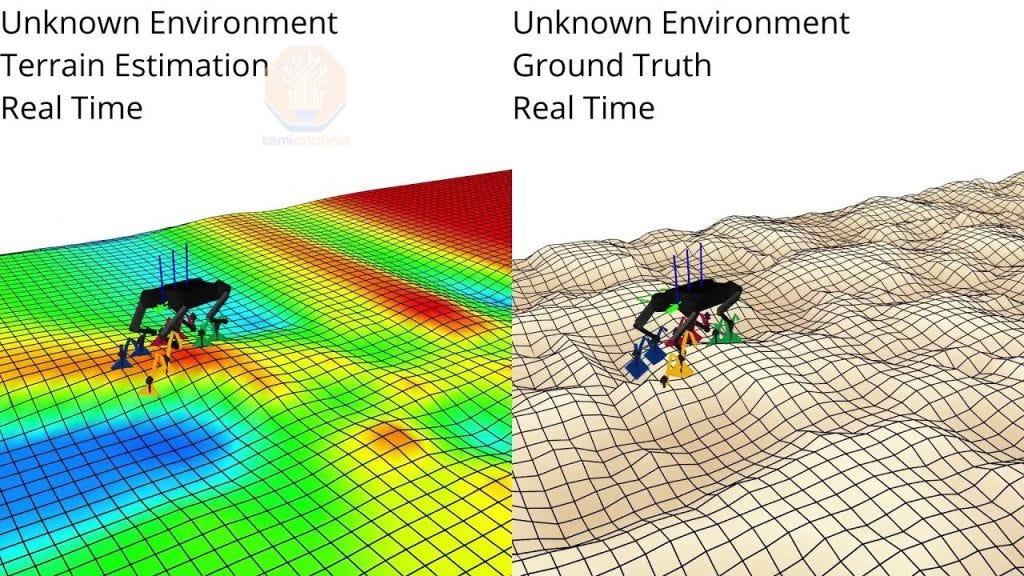

This Agency is complemented by a gain in locomotive Dexterity. Instead of collecting data on many possible configurations via real life deployments, or hard-coding heaps of control, simulators step in hugely to tackle the locomotion Dexterity issue. Simulation environments now provide robust, extensive training platforms to rapidly iterate locomotion control policies on heaps of environmental configurations, often far more difficult than the deployment environment.

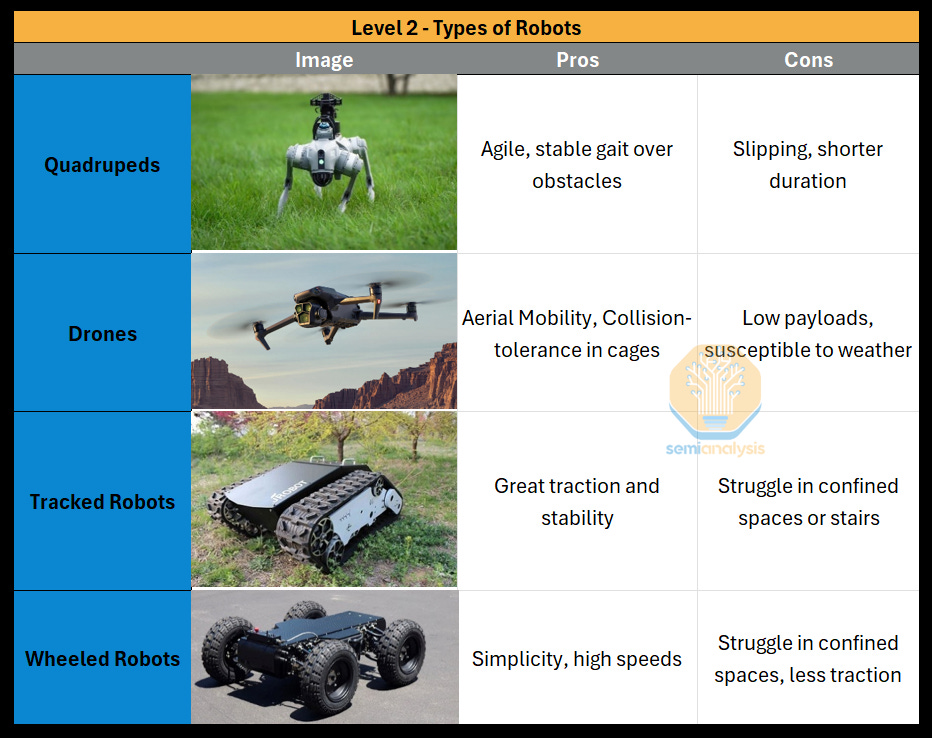

These simulators improved enough that much of these learned locomotion skills transfer to real world deployment with enough fine-tuning, significantly mitigating the “sim2real” gap. Now, the robot can use their new locomotion Dexterity to robustly, and agilely, traverse uneven ground, inclines, unstable ground (rocks, sands, construction pallets), and even locomote with a broken motor. With these unlocks, we see quadruped locomotion hitting its improvement inflection point in Level 2.

Hardware Boosts

Lastly, developments in hardware have enabled these robots’ autonomy by equipping them with adequate means. Onboard compute advancements, like the Nvidia Jetson, has enabled robots to ingest and process significantly more data. Multiple sensors, cameras, and LiDARs can now all be used to generate high-quality, real-time perception data, enabling rapid adaptation to the inherent randomness of the environment. Lastly, high efficiency actuators and enhanced batteries enable these robots to operate in the open world for long-horizon tasks.

Deployment and Considerations: Agents In The Open World

The robots of Level 2 may come in the following form factors:

But notably, the quadruped is unlocked. Advancements in large-scale simulation platforms enable robust control of their four legs to traverse with Dexterity, and their Agency can determine the scene and plan, both challenging prior to Level 2’s unlocks.

Importantly, these robots in Level 2 no longer require millions of dollars in facility engineering. Their general-purpose autonomy means they can be deployed in a new environment in as little as 1-3 weeks to learn their domain and perform tasks reliably. However, battery duration determines how many robots or chargers will be needed for a site. Since quadrupeds might average 90 minutes of battery life, one might buy more quadrupeds or charging stations, ramping costs.

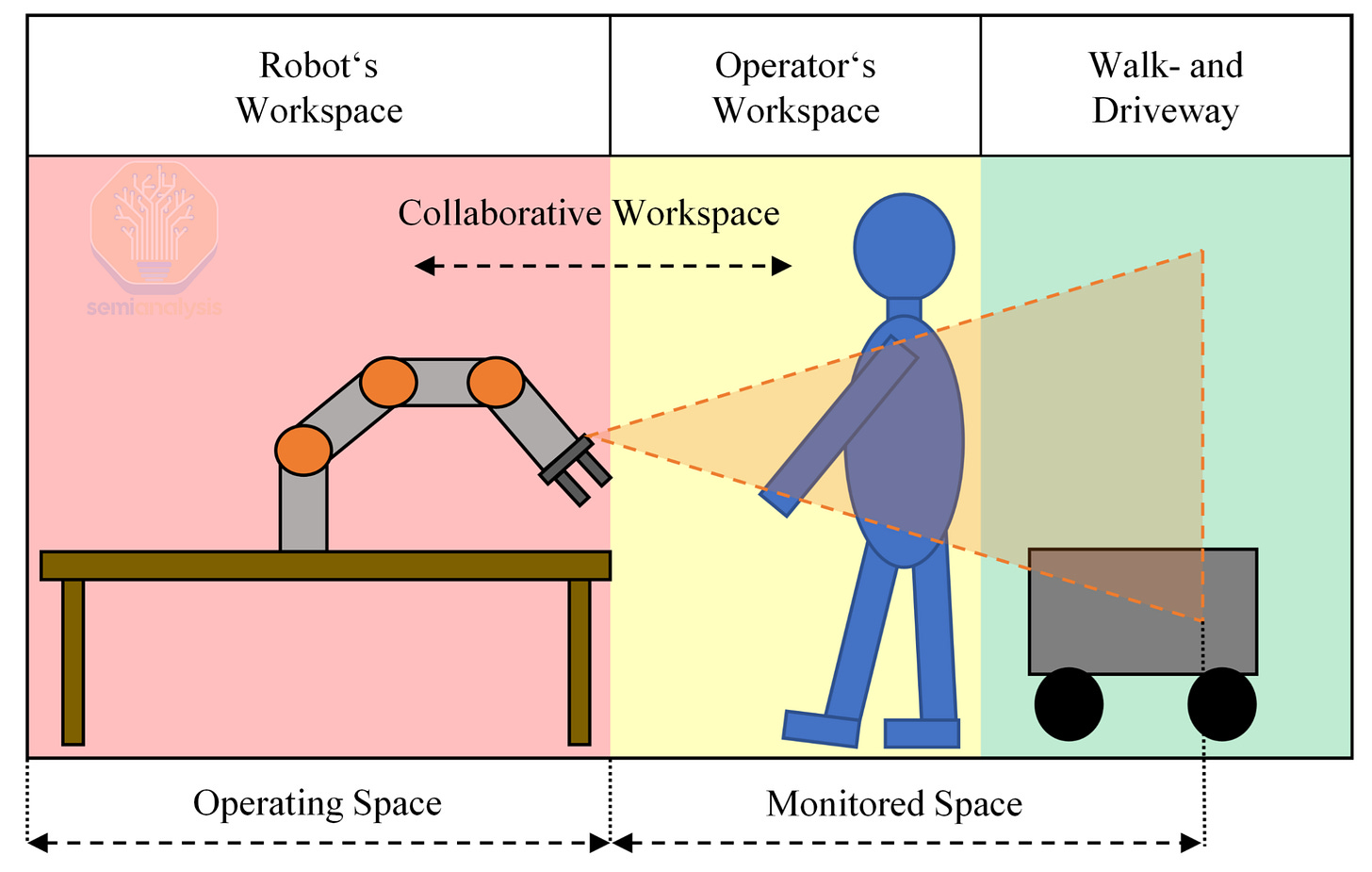

This freedom introduces a new question in the workplace: safety. In the case of the robots with autonomous mobility, there is no way to unplug them if they fall over or catch on fire. Their challenges shift more toward ensuring no property damage or human harm is done. For example, the open-world terrains may pose a danger to those around the robot, like a slick surface leading to a 70lb quadruped falling onto someone’s foot, or tumbling down the stairs into someone. Some measures implemented might be:

Robust collision avoidance - steering the robot clear of static or dynamic obstacles

Speed and separation monitoring - tracking nearby humans allows them to maintain a safe distance

Operational guidelines and audible or visual cues to signal the robot’s presence or intentions to its human coworkers

Implications: Unlocking Inspections and Data Collection Roles

Through autonomous mobility, these robots could be seen locomoting around open-world domains, deciding their paths, avoiding obstacles, and traversing various terrains up to hours at a time. These autonomous robots often perform in massive domains, like construction sites, oil and gas sites, chemical plants, and campus-like environments. The key is they automate data collection and inspection tasks, tasks that only require autonomous mobility and some data collection tools. These types of sites and tasks are nuanced, often:

Too large to be effectively inspected by a human(s) or sensorized cheaply

Too critical to risk a poor execution by a human(s)

Too dangerous for humans to continue

Robots now add another portion of the labor market to their belt. Let’s see some examples.

Construction

Sometimes, less than half of what’s planned for a construction site in a week will get accomplished, and with multiple facets like plumbing, electrical, putting up walls, etc, respective progress can be lost in the mix. Oftentimes some 40% of construction reworks stem from poor documentation, and this may cost up to 20% of the bill. A full inspection, or “capture,” of the site should resolve this, but for the construction company it means blocking an 8-hour workday for their most senior superintendent, and lack of specialization or objectivity may still affect the capture.

Instead, many outsource this to external companies. For example, a 200-room hotel project might be sufficiently large under state regulations to require a civil engineer or licensed surveyor to perform the capture. These might happen every other week and exceed $1M. A robot with autonomous mobility can handle these captures itself, attaching the appropriate cameras/sensors/LiDARs for a more objective and detailed capture. Once finished, it can potentially locomote into a second site and perform another job that same day, something a human crew would struggle to match.

Oil & Gas

A mid-size refinery may invest several million dollars over multiple years of implementation phases to fully sensorize its machinery—tracking leaks, vibrations, and heat. While the cost and timeline are significant, the investment is critical: a single hour of unplanned downtime cost up to $500,000. Instead, a blast-proof quadruped with the right sensors can patrol multiple sites, collecting more granular data, like diagnosing a heat map, at a fraction of the cost, and keeping humans out of harm’s way.

Critical Infrastructure

Inspecting windmills, electrical yards, and offshore rigs are all critical jobs, but they pose a great danger to humans and often require shutdowns to allow the human inspections to take place. For example, a legacy datacenter might shutdown in heavy rain and require substation inspection. Instead, we’ve heard quadrupeds have been able to automate this inspection without shutdown, saving the facility an estimated $350K in one year, and potentially human lives.

While these are great examples, they are in early production stages, and are currently being deployed at more sites like semiconductor fabs, steel factories, rail infrastructure, or for last-mile delivery.

Snapshot of Today’s Autonomy Challenges for Level 2

Autonomy in robotics is currently seeing a number of difficulties that will affect how well robots perform each Level. These are how the challenges currently affect the robots from competently performing in Level 2, and how they might be worked around.

Agency brings about new challenges, typically patched up with enough fine-tuning, but not resolved. To operate better in social settings, robots will need more social awareness in figuring out what a human is asking them to do, or the preferences of which human to listen to. While planning capabilities are unlocked, robots might still misjudge positions, leading many to rely on LiDARs as a safety check.

Compound error still remains an issue. Robots still aren’t highly accurate in their navigation and positioning. Most might use AprilTags placed around points of interest--like a specific location to perform another task-- to ensure accurate positioning instead.

Dexterity in locomotion is still a challenge, and uses workaround solutions. In Level 2, this means terrains, like deep mud, ice, or transparent glass, currently remain difficult to cross and might require extra tuning, or be avoided altogether.

Coordinating many degrees of freedom--the number of ways a robot can move-- is still hard. For example, bipedal locomotion does exist in Level 2, but adding more Degrees of Freedom (DoF) adds a layer of complexity that complicates stability and accurate navigation. Extra engineering, like AprilTags or specialized policies, might be used to patch up these issues as bipedal walking becomes more stable for various players.

Looking Forward

Promising Sources of Progress

These autonomy challenges are seeing improvements in a number of ways. For Dexterity, simulation platforms for locomotion could continue to improve, enabling more robust terrain traversing. Bipedal locomotion should see improvements with further data and learning.

Agency should see increases via more data and further learning. Synthetic data generation is currently underway with visual data augmentation in VLMs, where the data is slightly altered to generate more, diverse data for increased learning. LiDAR may begin to peel away from the robots as visual reasoning in the VLM increases. We could see AprilTags being used less as this visual reasoning and localization improves. Furthermore, open-world deployments help gather more data on edge cases, potentially bootstrapping better synthetic data, and scaling learning. As these challenges are resolved, we expect robots autonomy to improve and consistently deploy and improve until high automation of their target markets.

Level 2 marks the beginning of general-purpose robotics. The leap into Agency provides the cognitive foundation for all future advances, and the next step is to add manipulation to this general-purpose autonomy.

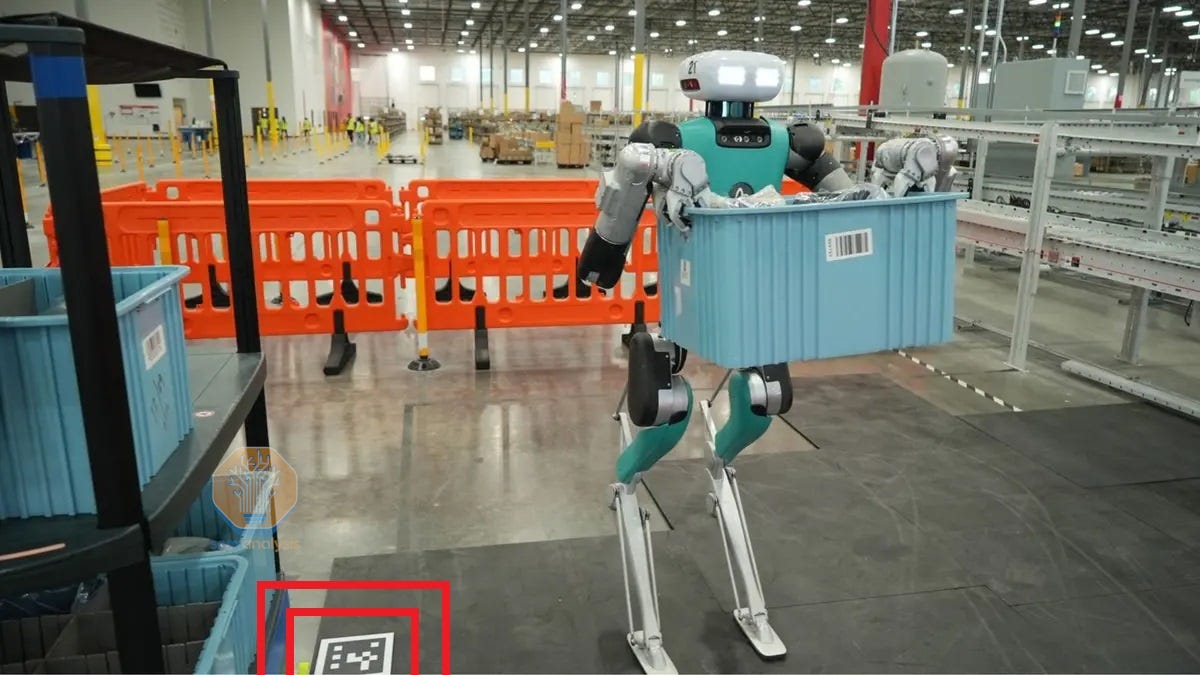

Level 3 - Low-Skill Manipulation

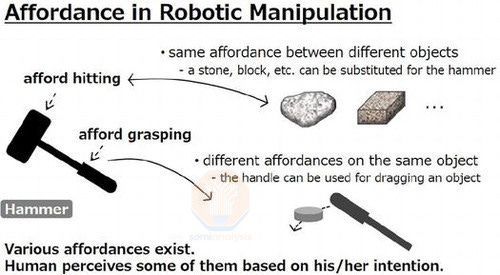

We’ve seen in Level 0’s automation that scripted automation and manipulation is economically invaluable, building cars at superhuman speeds, but limited to engineered tasks. Level 1 showed what it was like to break away into Intelligent Pick and Place, but the robots were only viable in a very limited set of use cases. In Level 2, we saw that Agency in robotics is incredibly valuable for safely operating in open-world domains over long time horizons. Now in Level 3, robots see the advent of a basic type of generalizable manipulation:

Manipulation: The ability to purposefully and contextually interact with the environment and change its state, like pushing open a door, grasping from a handle, holding a box from its edge, etc.

A robot may perceive an object well, but this doesn’t mean the robot has the necessary skills to interact with it. In Level 3, robots now understand how an object affords manipulation, and now have the Dexterity to directly generalize the motions for this manipulation. Using the robot’s Agency, these manipulation capabilities can be longer-horizon with multiple steps of planning. Both capabilities are a departure from Level 1’s short-horizon, angled grasping. Combining this generalizable manipulation with the autonomous mobility gained from Level 2, we now see the introduction of general-purpose mobile manipulation in applications.

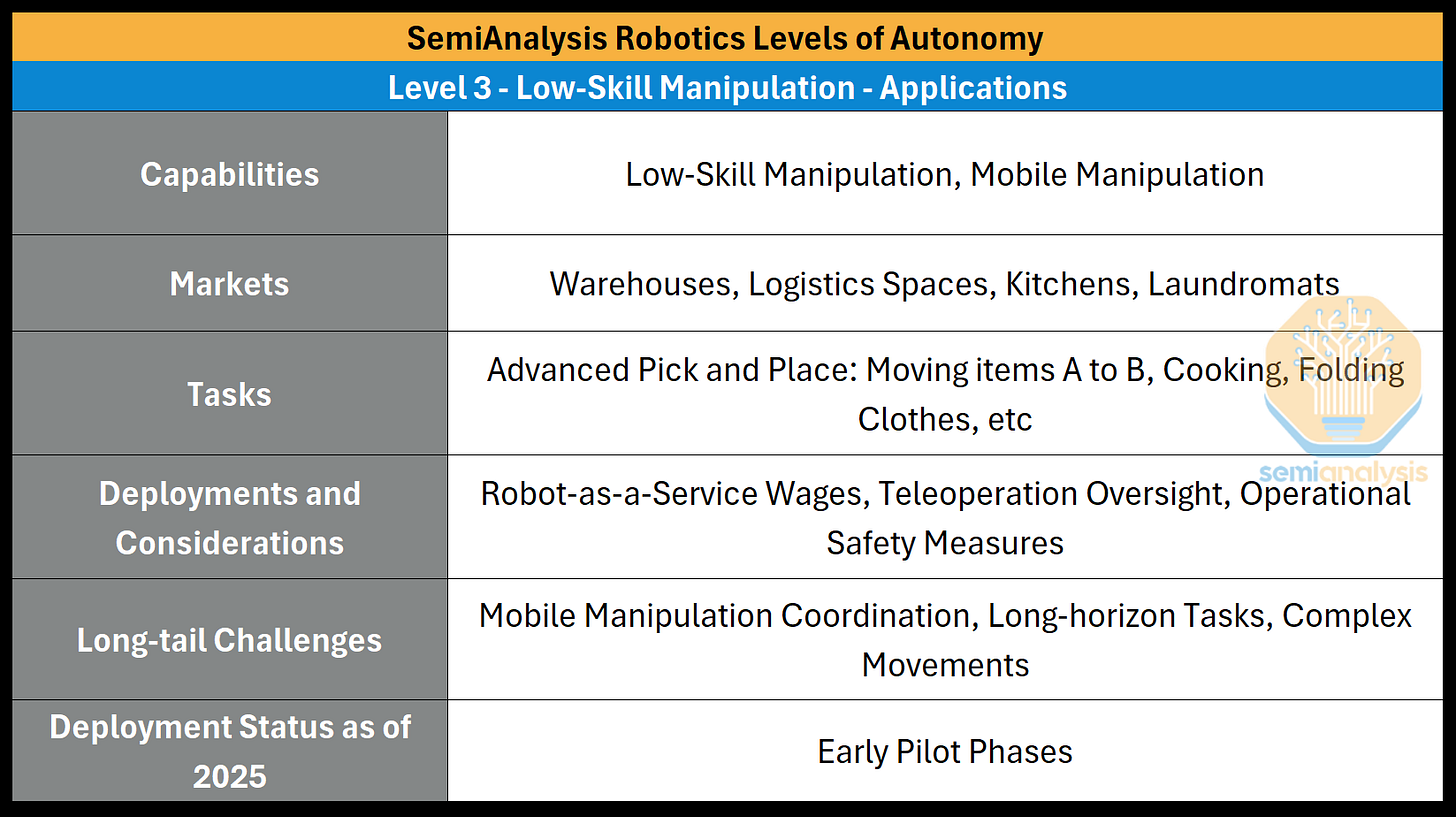

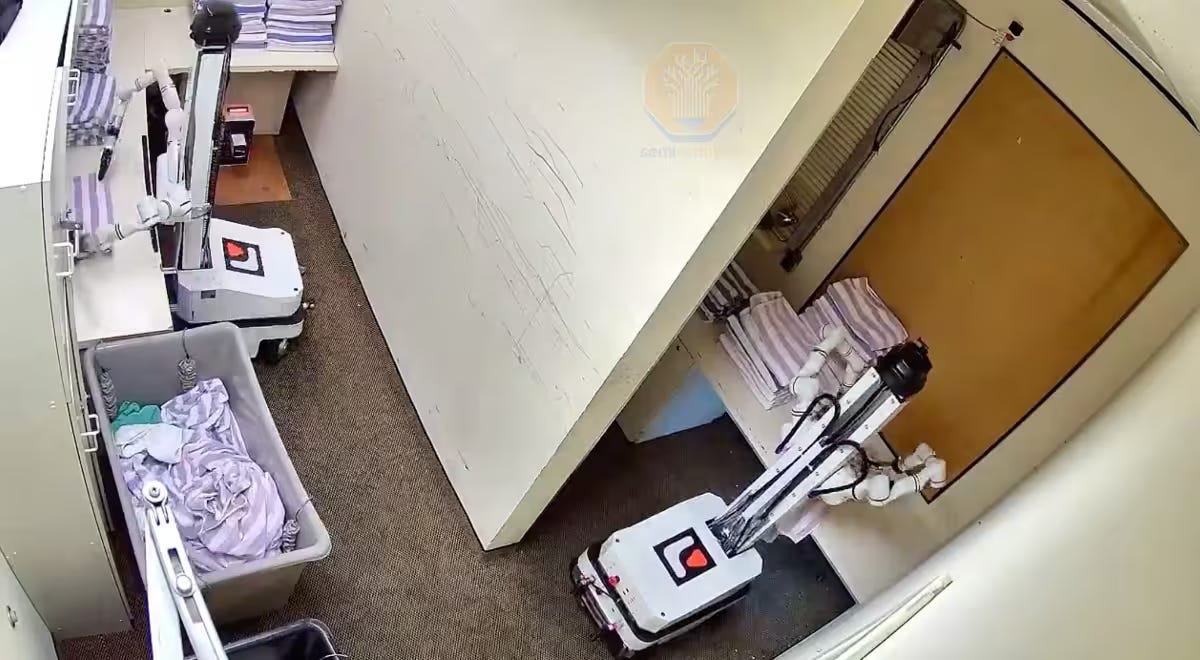

Level 3 marks the first generation of general-purpose robots that can target trades, moving from basic tasks in Level 1 toward skills, like cooking or cleaning. Early pilot programs are underway in domains like kitchens, laundromats, factories, and warehouses. However, their low-skill tasks, which we call "advanced pick and place," are modest, longer-horizon tasks: manipulate/pick an object, potentially locomote elsewhere, and perform further manipulation, or "place" the object. While modest, this capability is being used for cooking, folding laundry, and sorting/organizing non-delicate goods. Deployment in Level 3 is drop-in, the robot learns from human teleoperation --controlling the robot remotely-- and interfaces -- like tablets-- instead of months of time and millions of dollars of engineering.

General-purpose robots fulfilling Level 3 tasks can automate a distinct slice of global labor, albeit not the full spectrum of human labor-- an implication promised by Level 4. Currently, the aforementioned early pilot use cases for Level 3 are showing themselves to work, and their tasks fall under the following conditions:

Large Success Criteria: The task doesn’t quite have a precision constraint, i.e. moving an object from bin A to bin B, placing a cup on a table, stirring a pot, moving a box from location A to location B, etc

Low-to-no throughput or asynchronous: The task has a low pace to match, no throughput calculation to fulfill, or can be done asynchronously to the other jobs being performed, i.e. overnight

Retriability: Akin to Level 1, the task needs to allow for retries such that a failed execution does not damage property, or especially in Level 3, harm a person

No Sense of Force or Weight: These robots currently have no sense of touch, and only rudimentary force feedback at the joint level. They are likely unable to perform fine-grain, force-dependent manipulation tasks, like twisting novel bottle caps.

Current View - Early Stages

The Need - Generalizable Manipulation

In order to manipulate objects in an environment where everything is constantly subject to change, weakly intelligent grasping capabilities, like Level 1, won’t suffice. The robot must be able to adapt its motions to adequately manipulate the object in the context given. This requires generalizable manipulation, where physical AI imbues the Dexterity to sufficiently generate task and environment specific motions to manipulate the object.

Learning Manipulation - What’s Meaningful Today

While Level 3 is still at a very early stage, we see meaningful results in generalizable manipulation coming from VLMs. Currently, VLMs have improved, granting further spatial reasoning, and adding the capability to output Actions. But to output actions, we still need the robot to learn from action data.

Open-Source and The Data Increase

In Level 1, we saw how challenging the data scarcity issue could be. Luckily, robotics has been experiencing a fortunate relative increase in data, with developments in low-cost teleoperation hardware, like GELLO (2023), enabling users around the world to collect and open source their robot action data. Many datasets have been released over the past few years, slowly amassing sufficient data for learning basic manipulation tasks. Now, if we train our VLM with this action data we arrive at a new type of model.

Vision-Language-Action Models

Or VLAs for short, extend Vision-Language models (VLMs) by adding an action modality. Trained on paired image/text/action data, either end-to-end or by fine-tuning, a VLA means the VLM can read the scene, interpret the task, and now output an Action plan. These VLAs might come in two forms:

Task-specific: A VLM or modified VLM for high-level planning, and additional models for certain tasks/actions

Singular: One single VLM model performing all reasoning, planning, and Action

The model’s Agency understands “what” the task is and can plan accordingly, and the model now directly outputs the Action plans itself, leading to immediate Dexterity improvements. Pulling from its vast, internet-scale knowledge, the robot now comprehensively parses a new task and environment, and the Action of VLA performs novel, fluid motions on the fly, tailored to the scene.

Tasks that were once terribly complex from just a few years ago become tractable now. The “holy grail” from Level 1 of folding clothes is now feasible, no longer having to enumerate and calculate each wrinkle in the shirt. The VLA understands abstract concepts like a “sleeve” or a “collar” from the internet data, multimodally reasons over how the task is performed, and now plans and outputs the desired manipulations.

Longer-horizon, abstract tasks can now be approached as well. In these models, the task of “clean the bedroom” can be very confusing without the ability to understand what’s “wrong” in this specific bedroom and how to clean this bedroom. Now, it can be broken down with the VLA’s higher-order planning into chains of context-based subtasks like “pick up the pillow” or “adjust the blanket,” all chronologically ordered by the model, and producing the appropriate action plans.

We acknowledge that Level 3 tasks don’t require incredible accuracy or force and weight understanding, leaving high accuracy constraints aside. Additionally, these robots will likely be slow, due to the delicate, meticulous nature of teleoperation demonstration data from which the model learns. Furthermore, the addition of manipulation/Action to the VLM significantly eats up context windows and reduces the time horizons we had in Level 2, currently making these tasks up to only a few minutes long.

However, like the advent of VLMs in Level 2 creates a positive feedback learning loop continuously improving navigation, VLAs may create the same cycle for robotic Dexterity. As the robot continues to act and reason in the physical world, it can continue to collect data, learn, and improve. While VLAs hold great promise, they may not be the full solution either: task-specific modules/policies may be implemented for precise low-level control, whereas compliant control may be used to yield against opposing forces, and many other methods.

This Level of Autonomy and the advent of mobile manipulators now propose a monumental leap into larger-scale labor replacement.

Deployments and Considerations: Robot Coworkers

The robots of Level 0 and 1 might require multi-million dollar engineering projects and custom software integrations like those for the Warehouse Management System (WMS). However, robots targeting Level 3 can be deployed more like a human employee. Some companies drop them into sites, let the teleoperator read the tablet, and perform the workflows to gather data and teach the model. Teleoperation amounts will vary by task complexity, but the teleoperation cost is low, typically outsourced to emerging markets and often backed by investor subsidies.

This ease of integration fundamentally changes the economic equation. The key metric is no longer a multi-year ROI against a massive capex. Rather, these robots can become revenue positive within days by charging an hourly wage in a Robot-as-a-Service model. This demolishes the previous barriers to entry of Level 0 and 1 that kept out most medium-sized or smaller firms, making these robots now accessible to a wider range of businesses.

While mobile manipulation exists, it’s very early and still faces safety questions. It must reach the task site and know its positioning before acting, as any misalignment might damage property or injure people. Early deployments may likely stay in fenced off zones until these physical safety challenges are addressed.

Bipedal platforms are attractive to some because they enable a “bending” at the hips for tasks. However, bipedal locomotion, walking on two legs, is an inherently unstable act. It requires constantly shifting balance to ensure the next step is accurate. Carrying objects now adds a new mass that the locomotion must account for while it walks. Initial bipedal pilots, while maybe functional, could be substituted with wheeled-base robots instead.

Robots operating around humans demand stringent safety requirements. Since a robot's autonomy is lacking in early stages, some safety measures may still need to be enacted/put in place. Teleoperation oversight--where the robot is monitored by a teleoperator-- is currently a must for these robots in case something goes awry and a human must intervene. Nevertheless, complications could still arise, e.g. teleoperating a robot after a failure has occurred, latency issues in the teleoperation, etc. For more immediate measures, some deployments might use:

Potential Fields: Spaces a robot maps around objects and the forces they might cause to the robot

Risk aware modeling: Assessing the probabilities of a collision occurring and planning accordingly

Speed and separation monitoring: As we saw in Level 2, keep track of humans and maintain a safe distance

With deployment considerations covered, what roles are currently being attempted for Level 3?

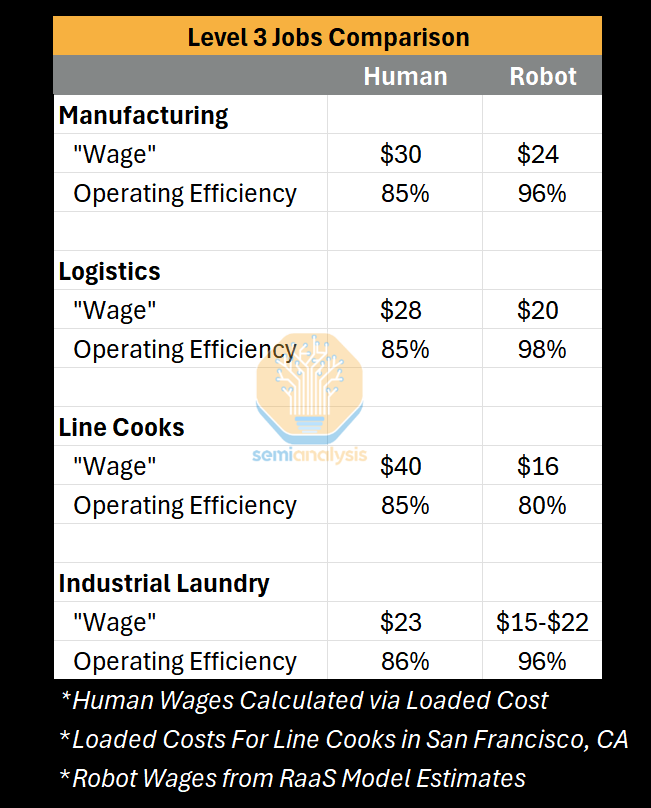

Implications: Low-Skill Labor Replacement

While a primitive form of generalizable manipulation exists in Level 3, it’s still very early. The current pilot tests of robots find their tasks fulfilling our earlier conditions: large space for success criteria, low-to-no throughput or asynchronous, retriable, and require no force or weight sensing. In stationary applications, the robot may perform a chain of manipulations to complete a longer-horizon task. But most of the time the robot will use its mobility, like picking a non-delicate object in location A and locomoting to location B to place the object. With these new capabilities, robots add a significant portion of the labor force to their arsenal.

While our current conditions are unique traits for roles, they are sizable, and fairly costly. These robots gain an edge the same way Level 1 aimed to: mitigating the loaded costs. For example, restaurant turnover rates can reach up to 170% yearly in San Francisco, and the hiring, onboarding, training, missed shifts, and productivity ramp lead to a higher cost than just low-skill wages. Below are the current roles we see robots attempting in Level 3.

Cooking in Restaurants or Food Service: The ingredients are pre-portioned for the robot and it can perform the longer-horizon, lenient task of cooking them together with basic, chained manipulation. Restaurants tend to be the most labor intensive industry, requiring some 3x the employees of a hospital to generate the same $1m in revenue.

Industrial Laundry: The once impossible task of manipulating deformable objects becomes a viable overnight job, currently folding repeated items, like towels, sheets, pillowcases, napkins, etc

Logistics: “Just-to-stock” workflows, like non-critical stocking of the warehouse line or setting up replenishment zones, both without time or space constraints. A robot may pick a variety of items in one location and place them in another, for example: replenishing shelves, rotating totes, or transporting goods or bins across the facility.

Manufacturing: Performing line-side transference and replenishing the assembly line and stock on the side of the line. For example, part sequencing and organizing materials for next day’s assembly.

There are other tasks that could meet our criteria for current Level 3 tasks that we have not listed, like hedge trimming, landscaping, or other maidwork. While other roles might seem to fulfill our large space for success criteria, low-to-no throughput calculation, retriable, and with no force or weight sensing, we are still too early to tell what will happen.

Luckily, there are niche roles, as listed above, that only require low-skill manipulation capabilities and often autonomous mobility. With these roles, high loaded costs of workers, and a superb RaaS model wage, Level 3 makes great drop-in replacements of labor. We expect these robots to automate increasing portions of low-skill labor as they improve. Yet, at this paper’s release, these robots are still very early, and are facing their own hurdles.

Snapshot of Today’s Autonomy Challenges for Level 3

While Level 3 is in very early stages, there are still some difficulties in getting the robots working reliably. Memory architectures are not yet sufficient for generalizing past experiences, limiting how well the robots may perform tasks in new situations. Localization and compound error makes it hard for robots to precisely navigate toward their task and position themselves for the manipulation. Some might use AprilTags for this, employ analytical methods less subject to error, or tune the robot enough to reliably perform the task.

While these capabilities exist, it’s not an easy or cheap feat. Teleoperators might be used for some time, the robots won’t be terribly fast, and adding new movements only increases the difficulty. Complex movements, like whole-body control--like twisting or bending-- add another layer of difficulty to the problem. Many of these problems for Level 3 could be approached with further data for learning, but mobile manipulators are very data hungry and still early.

Looking Forward

Promising Sources of Progress

While Level 3 is seeing deployments and economic implications, we are at a very early stage. VLAs and teleoperation data are showing meaningful progress at the moment, and may continue to scale learning, or other avenues of progress may help. Simulators may step up for manipulation learning. We have early evidence of massive speedups in simulators, and aspects of the sim2real gap have started to shrink thanks to some of the benefits of visual synthetic data. Synthetic data and data augmentation methods are advancing, proving to be useful in widening data collection for navigation, manipulation, and control. Or even furthering real data, like continued open-source data collection, or field deployments to gather domain-specific, task-specific, or edge case data. In most cases, we see larger, more diverse datasets scaling learning, refining their capabilities and resolving the current challenges.

Deployments

In their deployments, we expect these robots performing Level 3 tasks to slowly drop away from the teleoperation oversight and operational measures. The immediate measures, like potential fields or risk-aware modeling, should fade as autonomy improves. Teleoperation oversight will extend from the initial 1:1 robot:human to maybe 10:1, but this ratio should continually increase until the autonomy takes over. Additionally, these autonomous robots might end up connecting to the WMS directly, optimizing their tasks/actions and increasing throughput through full integration with the system.

While some might currently opt for wheeled-base humanoids, we expect bipedal locomotion to resolve. We’ve seen tangible progress in bipedal locomotion, with some tacking diverse terrains and becoming increasingly stable. While some might progress faster than others, we do expect this to impact Level 3.

There is potential for robots in homes in this Level, but they would likely be very restricted in scope and functionality. A bespoke robot might handle laundry and nothing else, thereby minimizing risk to humans. Owners might even teleoperate the robot or let it run only when the house is empty. However, all it takes is one mistake to smash a wedding photo and damage their reputation.

While capabilities may continue being refined and deployments accelerate, the last bastion of human-only tasks remains.

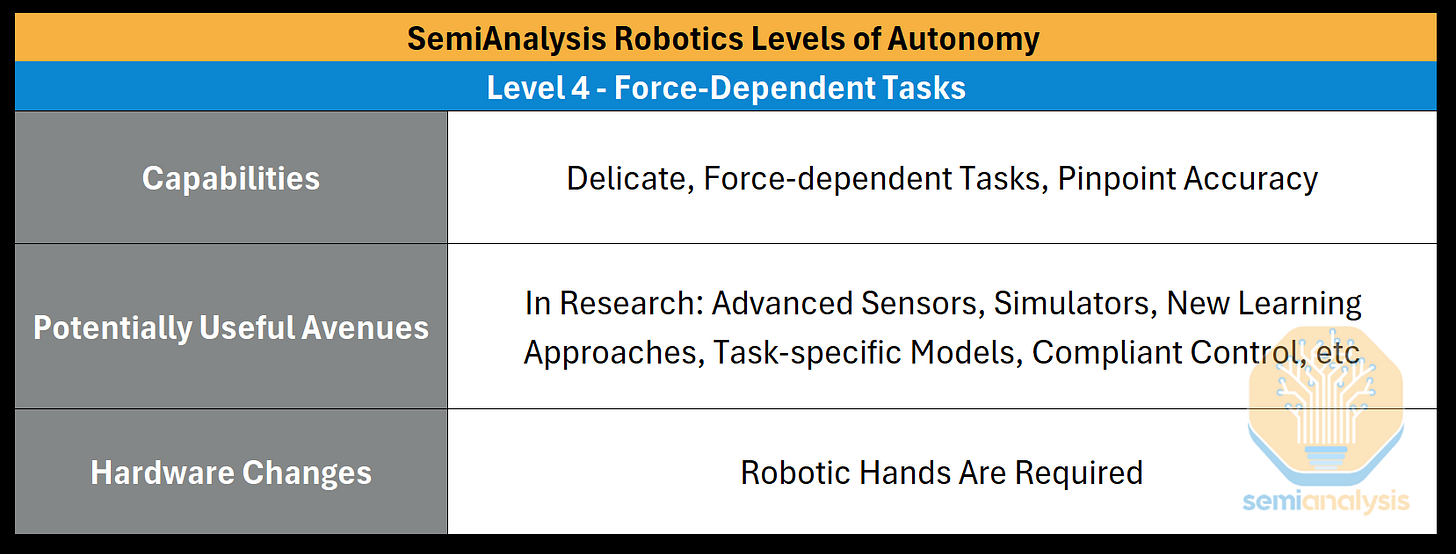

Level 4: Force-Dependent Tasks

Level 4 represents the final evolution where robots can perform force-dependent, delicate tasks with pinpoint accuracy. These tasks require the Dexterity to understand and react with nuance to the physical forces of the environment. The robot must perform skilled, fine-grain manipulation that requires a delicate, adaptive touch, a step above the low-skill manipulation tasks of Level 3.

We see the promise of a highly automated workforce fulfilled at this Level, opening the door to remaining labor tasks that, up until this point, will have remained exclusive to humans.

Looking Forward

This is still a domain under research, as such, we will detail promising sources of progress and expected implications, but not an exhaustive list.

Promising Sources of Progress

Manipulation can tackle many use cases, but being fundamentally “numb” to the physics of the task and objects at hand creates a hard ceiling on capabilities. In this Level, robotic “hands” enter the picture, equipped with tactile sensing or robust feedback loops to help bolster this sensitivity. Though this may not be the whole/final solution.

Open Debates

Scaling vision modalities has been effective for most tasks thus far, however there remains a set of force-dependent, granular tasks that have not been solved. Visual modalities currently struggle to pick up on these physical cues and solve these tasks, but some believe this can be resolved with further data. However, some believe that this is more than a data problem, requiring a different approach. For example, searching for a phone in your pocket is primarily done through tactile sensing, and while vision might be used for this, vision alone would make the task very challenging.

That said, there has been great progress in tactile sensing recently in both cost and effectiveness. Force and torque sensing is showing early signs of being useful in training as well. We believe force and torque sensing and tactile sensors may be useful components to the solution going forward, but it’s very early to declare any one approach as “correct.”

Potentially Useful Avenues

Level 4 is an area of ongoing research focused on imbuing this force and weight understanding into the robot. A number of angles could be used in the future to help bring force-dependent tasks alive:

Advanced Sensors: Tactile sensing on robotic “fingertips” might be used to gather data for learning by demonstrations and give the robot a sense of “touch”

Simulators: Large-scale simulation potentially ameliorating the sim2real gap

New Learning Approaches: Training VLAs on new streams of tactile and force data might enable the robot to connect seeing with physical interaction

Task-specific Models: Various individual policies might be used for specific actions or behaviors to correctly understand forces

Compliant Control: Control functions enable the robot joints to understand opposing forces and yield or work around them

There are many approaches, and likely more that are yet to be seen, that are being used to tackle the problem of force-dependent tasks. We acknowledge that the solution to these tasks may utilize any of these, a combination, or new developments yet to be discovered.

Level 4 Implications: Mass Labor Replacement

The unlock of these force-dependent, high-accuracy tasks opens the door to the automation of the majority of the physical labor market. As time goes on, we might see automation of:

The Skilled Trades: Plumbing, electrical work, and fine assembly tasks requiring an intuition of force and weight. With this unlocked, these jobs become automatable for the first time, addressing a global market.

The Service Industry: The fine motor skills allow the robot to automate the rest of the service industry positions across retail and hospitality sectors.

Manufacturing and Logistics: All remaining tasks in these domains, like complex packaging, delicate assembly, installation, and more are now possible.

As robots targeting Level 4 become more reliable and garner further trust, they will move into more profound roles, like disaster recovery teams dedicated to each country with no risk of losing a “life,” or autonomous space exploration where they may explore new worlds and set up camp for humans to arrive at later on.

Furthermore, the existential threat we posed in our first article, and the deeper dive from our coauthor Joe Ryu at Edge of Automation, may come alive here. A robot with Level 4 capabilities might be a superhuman laborer, leased out for much cheaper than human labor, and might be implemented to build identical robots at scale, shrinking labor costs down to unthinkable levels. Goods could become nearly inelastic and traditional market values might be upended as impossible production capacities come alive. The first country or company to reach this tier may set the terms of the labor economy and see a geopolitical upheaval, with some countries imposing border controls, or flat out bans of the robots and services coming from other nations.

The Time Is Now

The dream of general-purpose robotics is no longer a distant fantasy. It is being built now, one Level at a time. Each step on this path unlocks immense economic value and reshapes our world in profound ways.

We find ourselves much closer to the final chapter than many realize. The necessary Level 0 industrial arms showed us what robots were capable of in the right applications, even without autonomy. In Level 1 there was large promise from the new adaptability, but it came too early, leaving many with a sour taste in their mouth. However, new paradigms have made their applications much more viable. Now, Level 2 has arrived with foundation models, enabling the broad reasoning capabilities to unleash the Agency required of general-purpose robotics. This leap into Agency allows them to navigate our complex open world, and remains the genesis for multimodal reasoning capabilities in future Levels. Level 3 increased in Dexterity with its newfound manipulation capabilities, generalizing manipulation to various objects and environments, a dream of Level 1. Combined with the mobility of Level 2, Level 3 created the first genuine human labor replacement, despite having only basic abilities. Lastly, Level 4 represents robotics' future, where force understanding may be the last bridge into fully autonomous robotics, automating nearly all physical labor and creating new roles.

This framework is more than an academic exercise, but a tool for strategy. It allows industry stakeholders, engineers, and researchers to distinguish the blurred lines of robotics and focus their efforts where they may stand to gain most. The robotics evolution will not be a single, dramatic event but a steady, deliberate climb. We have laid out the ascent of general-purpose robotics with our Levels of Autonomy, designed specifically to cut through the noise of past failures, future hype, and hazy notions. In our upcoming pieces, we will detail who in the supply chain stands to win or lose, and what to expect as transformations continue to shift the landscape..