How AI Labs Are Solving the Power Crisis: The Onsite Gas Deep Dive

Bring Your Own Generation, Sayonara Electric Grid, Turbines vs. Recips. vs. Fuel Cells, Why Not Build More CCGTs?, Onsite Power TCO

The Grid is Old and Tired

Nearly two years ago, we were the first to predict a looming power crunch. In our report AI Datacenter Energy Dilemma - Race for AI Datacenter Space, we forecasted AI Power Demand in the US to grow from ~3GW in 2023 to over 28GW by 2026 – a pressure that would overwhelm America’s supply chains. Our prediction proved very accurate.

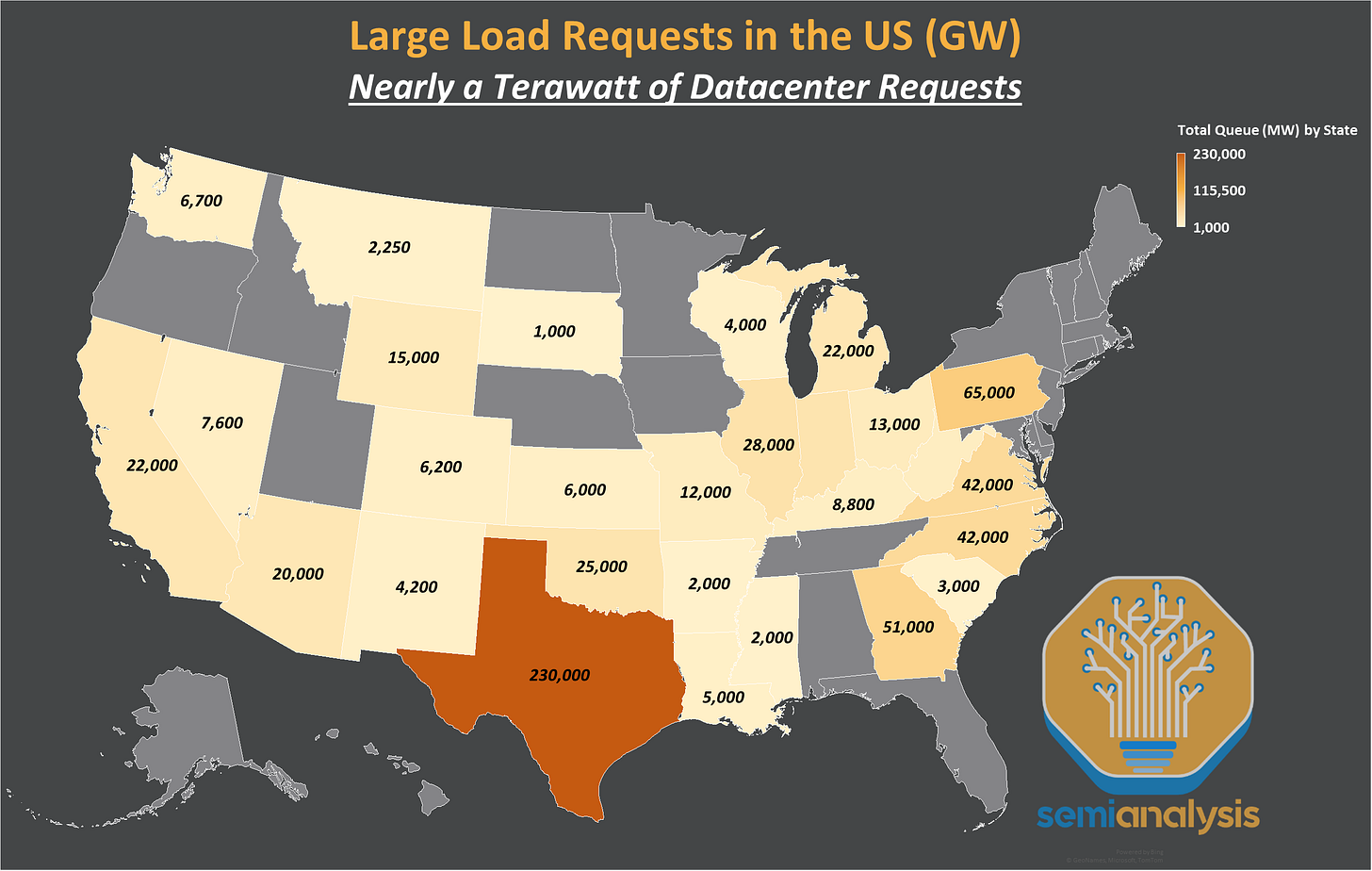

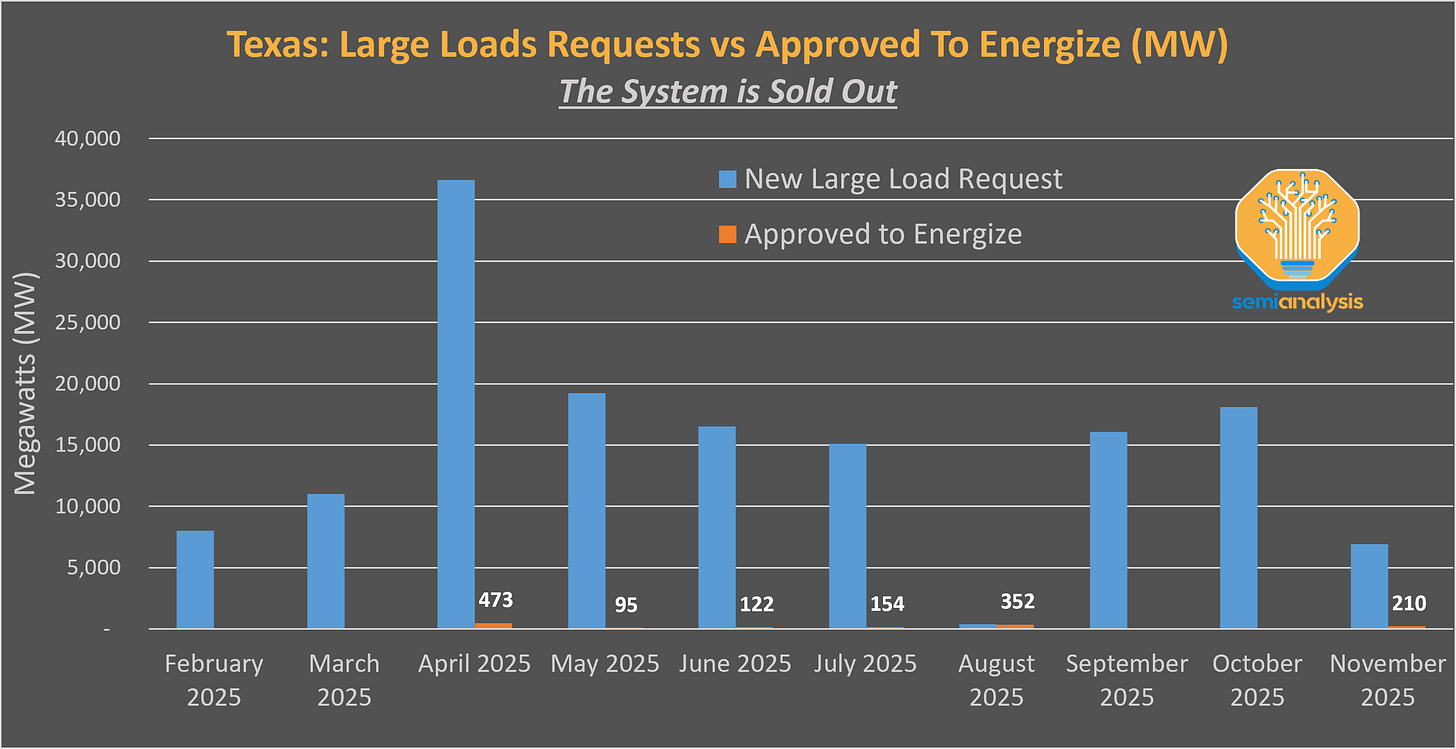

The chart below tells the story: in Texas alone, tens of gigawatts of datacenter load requests pour in each month. Yet in the past 12 months, barely more than a gigawatt has been approved. The grid is sold out.

However, AI infrastructure cannot wait for the grid’s multiyear transmission upgrades. An AI cloud can generate revenue of $10-12 billion dollars per gigawatt, annually. Getting a 400 MW datacenter online even six months earlier is worth billions. Economic need dwarfs problems like an overloaded electric grid. The industry is already searching for new solutions.

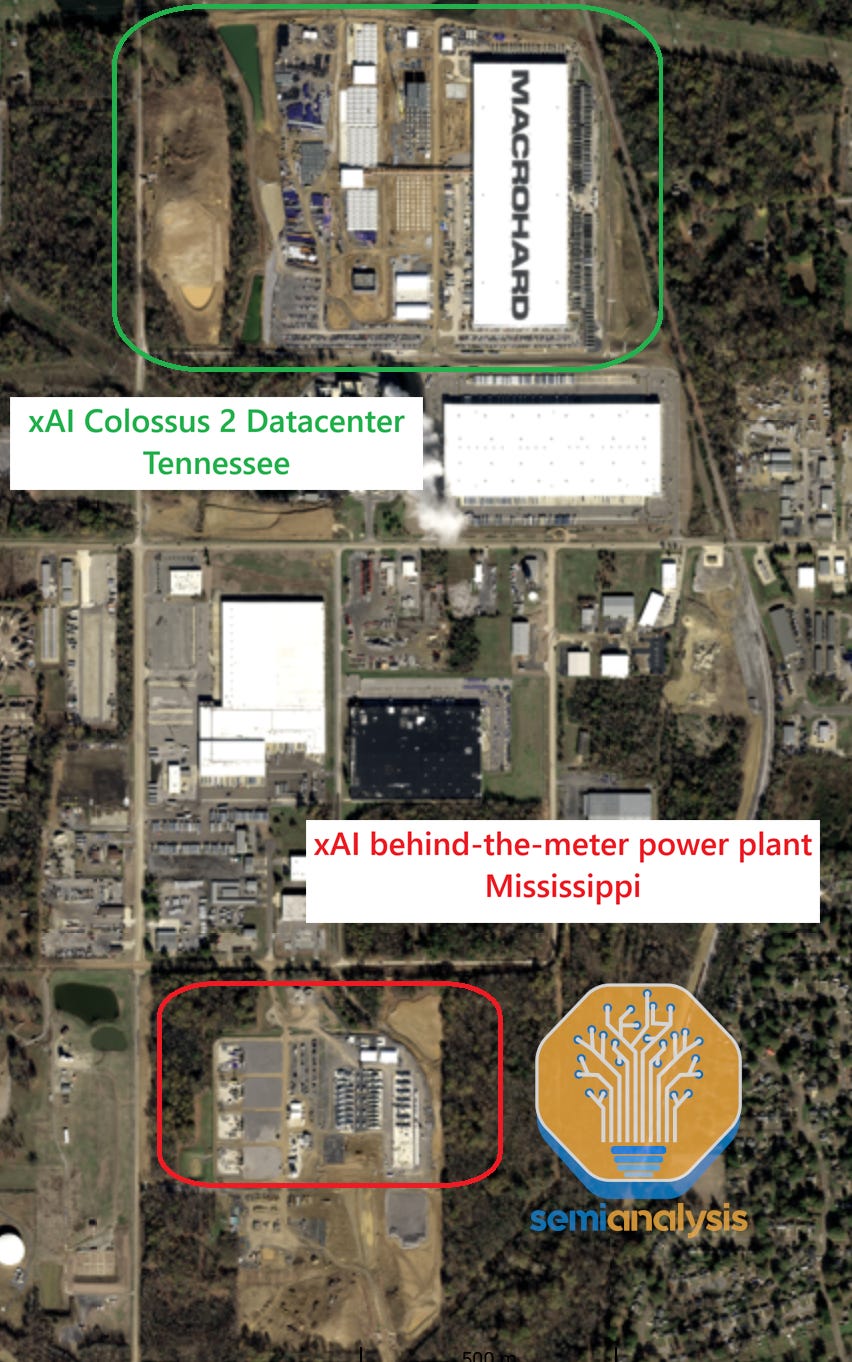

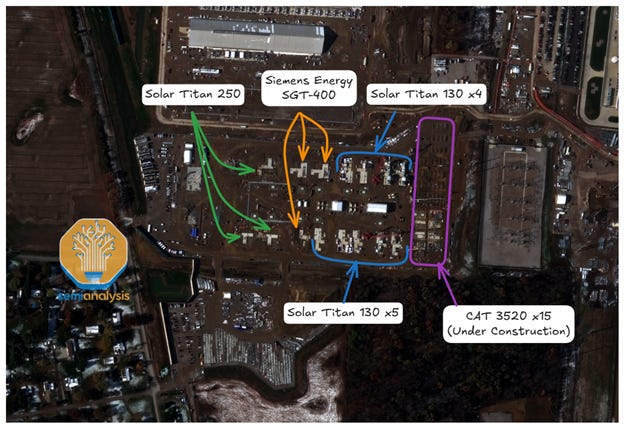

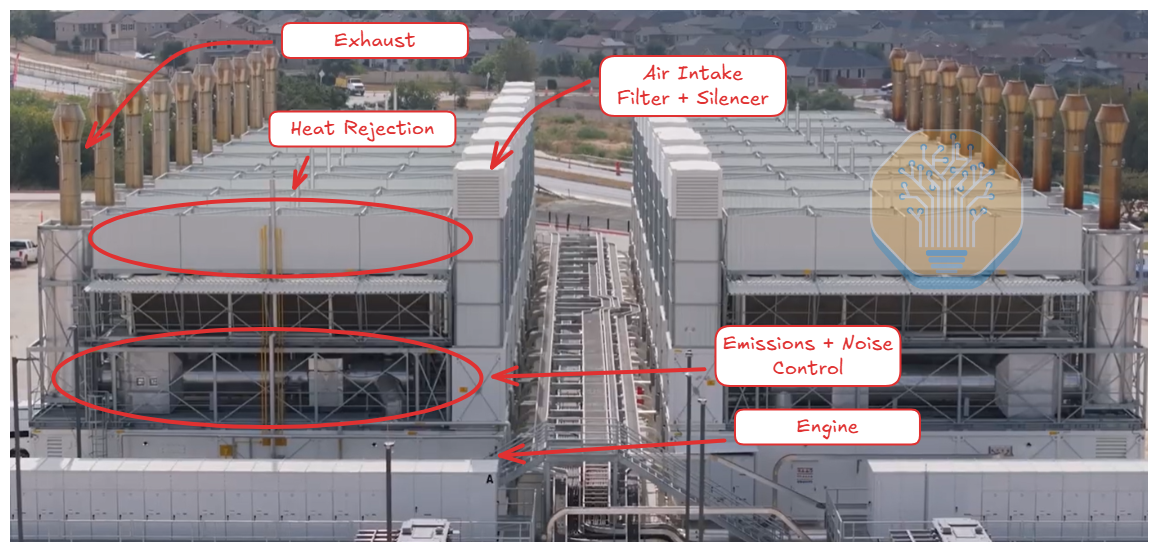

Eighteen months ago, Elon Musk shocked the datacenter industry by building a 100,000-GPU cluster in four months. Multiple innovations enabled this incredible achievement, but the energy strategy was the most impressive. xAI entirely bypassed the grid and generated power onsite, using truck-mounted gas turbines and engines. As shown below, xAI has already deployed over 500MW of turbines near its datacenters. In a world where AI Labs are racing to be first with a Gigawatt datacenter, speed is the moat.

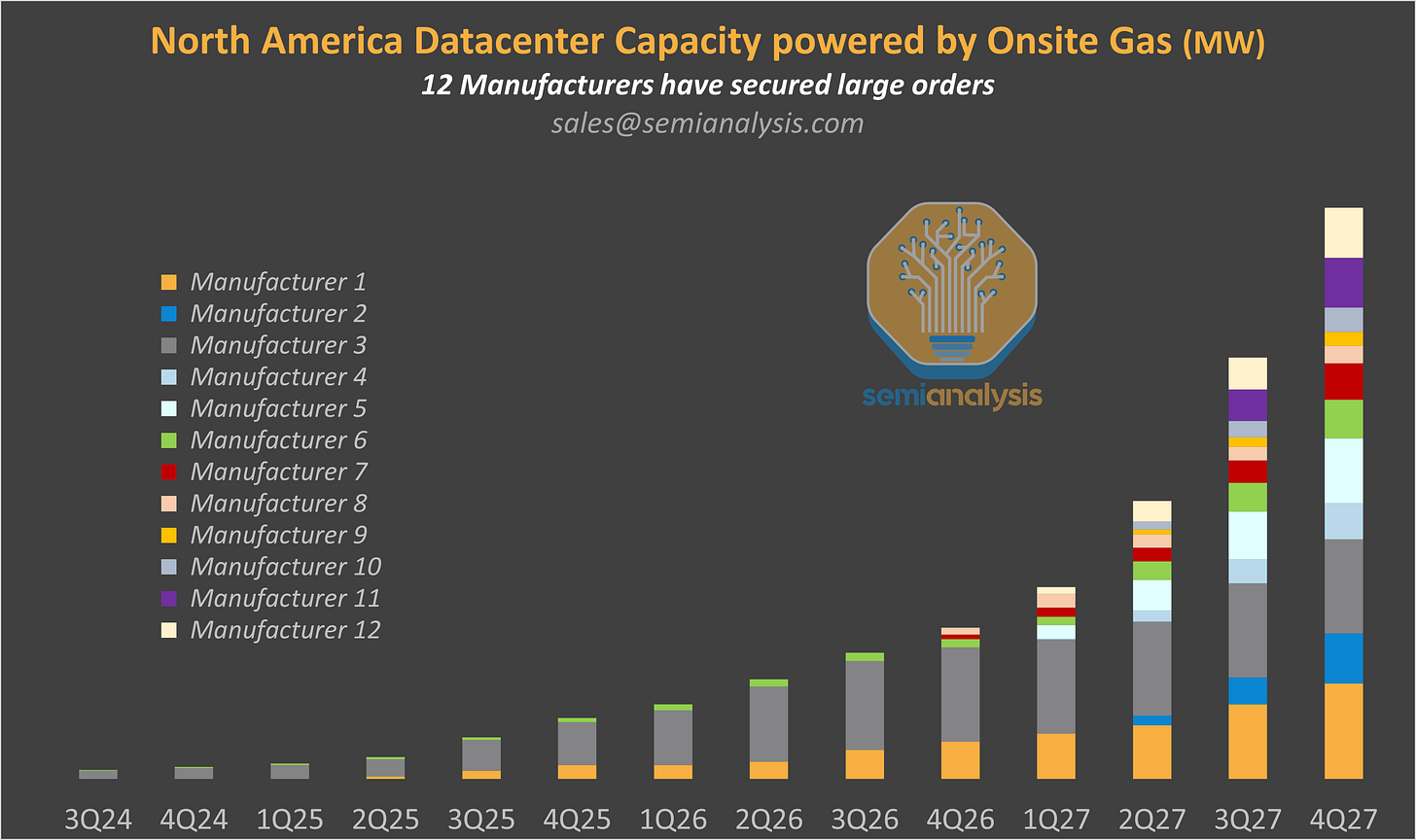

One by one, hyperscalers and AI Labs are following suit and temporarily abandoning the grid to build their own onsite power plant. As we discussed months ago in the Datacenter Model, in October 2025, OpenAI and Oracle placed the largest order ever for onsite gas generation, with a 2.3GW plant in Texas. The market for onsite gas generation is entering an era of triple-digit growth annual growth.

The beneficiaries extend far beyond the usual suspects. Yes, GE Vernova and Siemens Energy have seen their stocks surge. But we’re witnessing an unprecedented wave of new entrants, such as:

Doosan Enerbility, the Korean industrial giant, timing its H-class turbine launch perfectly. It already booked a 1.9GW order to serve Elon’s xAI - as we exclusively unpacked to our Datacenter Industry Model subscribers several weeks ago.

Wärtsilä, historically a ship engine manufacturer, realized the same engines that power cruise ships can power large AI clusters. It has already signed 800MW of US datacenter contracts.

Boom Supersonic—yes, the supersonic jet company—announced a 1.2 GW turbine contract with Crusoe, treating the margin from datacenter power generation as another round of funding for their Mach 2 passenger jets.

To understand growth and market share by supplier, we built a building-by-building tracker of sites deploying onsite gas in our Datacenter Model. The results surprised us: 12 different suppliers have now secured >400 MW of datacenter orders each in the US alone, for onsite gas generation.

However, onsite power generation brings its own set of challenges. Power costs are often (much) more expensive than via the grid, as detailed below. Permitting can be a lengthy and complicated process. And it’s already causing some datacenter delays - most notably one of the Oracle/Stargate GW-scale facilities, which our Datacenter Industry Model predicted three weeks prior to the Bloomberg headlines by analyzing the whole permitting process.

Again, clever firms like xAI have found remedies. Elon's AI Lab even pioneered a new site selection process - building at the border of two states to maximize the odds of getting a permit early! While Tennessee couldn't deliver on time, Mississippi happily enabled Elon to build a GW-scale power plant.

This report is a deep dive into Bring Your Own Generation (BYOG). We begin with why the grid can’t keep up, then provide a technical breakdown of every generation technology available to datacenters—GE Vernova’s aeroderivatives, Siemens’ industrial turbines, Jenbacher’s high-speed engines, Wärtsilä’s medium-speed engines, Bloom Energy’s fuel cells, and much more.

Then we examine deployment configurations and operational challenges: fully islanded datacenters, gas + battery hybrids, Energy-as-a-Service models, and the economics that determine which solutions win. Behind the paywall, we share our views on manufacturer positioning, d and the future of onsite generation.

Is the Electric Grid Dead in the AI Era?

Before we dive into solutions, we need to understand why the grid is failing. To be fair, America’s electrical system has been the primary enabler of AI infrastructure so far. Elon aside, every major GPU & XPU clusters today runs on grid power. We’ve covered many of them in prior SemiAnalysis deep dives:

Microsoft’s AI Strategy showing the massive grid-connected facilities for OpenAI in Wisconsin, Georgia and Arizona.

Our Multi-Datacenter Training report, digging into Google’s massive grid-powered clusters in Ohio and Iowa/Nebraska, as well as OpenAI’s gigawatt cluster in Abilene, TX with Oracle, Crusoe and Lancium.

Our Meta Superintelligence article laying out their AI large plans, which include some onsite gas generation, but remain primarily served by AEP’s system in Ohio and Entergy in Louisiana.

Our Amazon’s AI Resurgence thesis, discussing AWS’ massive Trainium clusters for Anthropic, connected as well to AEP and Entergy’s infrastructure.

These insights appeared in our Datacenter Industry Model months or years before official announcements. Our model tracks dozens more large-scale clusters under construction for 2026 delivery and beyond—including their exact start dates, full capacity, end-users, and energy strategies.

But we’ve hit a tipping point. The large datacenters coming online in 2024-25 secured their power in 2022-23, before the gold rush. Since then, the scramble has been relentless. We estimate roughly a terawatt of load requests have been submitted to US utilities and grid operators.

The result is gridlock - literally. As we explained in AI Training Load Fluctuations at Gigawatt-Scale, the grid is slow by design:

Real-time balancing: Electricity supply and demand must match nearly perfectly, every second. A mismatch risks blackouts for millions, as we saw with the Iberian Peninsula blackout in April 2025.

System studies: Every large new load (datacenter) or supply (power plant) triggers deep engineering studies to ensure it won’t destabilize the network. And in some places, grid topology changes so quickly that load studies go obsolete before they’re completed.

When hundreds of developers simultaneously submit interconnection requests, the system seizes up. It becomes a prisoner’s dilemma:

If everyone coordinated, the grid could handle more requests faster.

FERC Order 2023 has pushed grid operators to adopt cluster studies for this purpose, but those reforms were solidified only in 2025.

In practice, “gold rush” behavior means developers submit multiple speculative requests to different utilities simultaneously

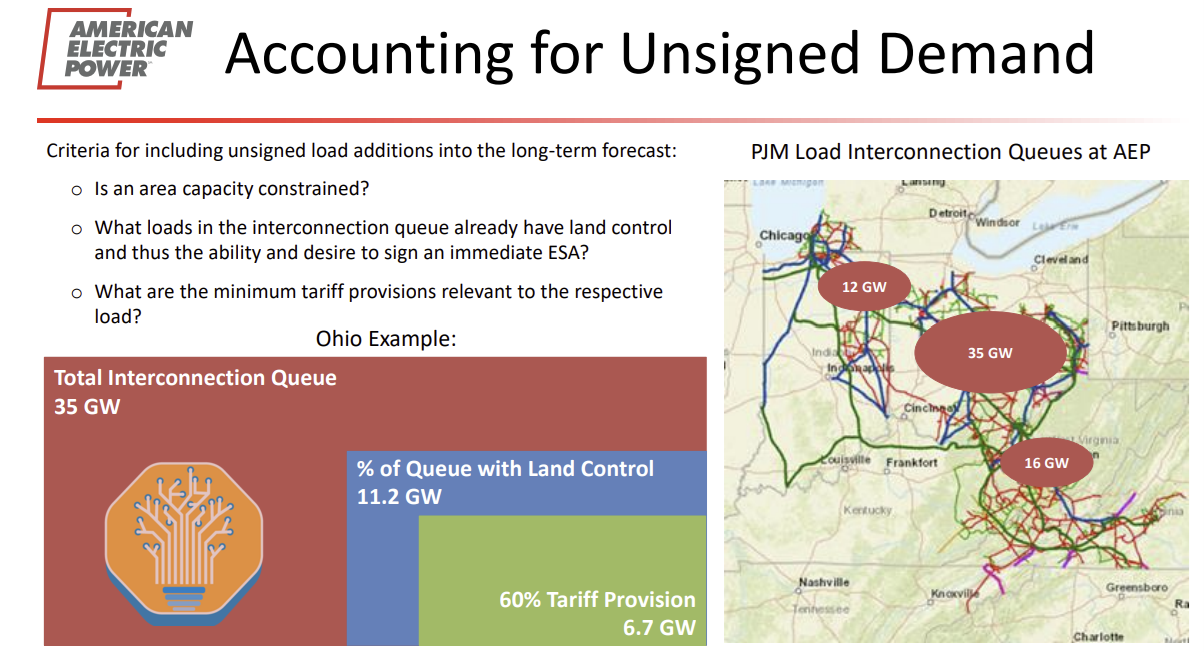

For example as of mid-2024, AEP Ohio had 35 GW of load requests—and 68% didn’t even have land control

Speculative requests clog the queue for everyone, encouraging more speculative requests elsewhere

The vicious cycle accelerates

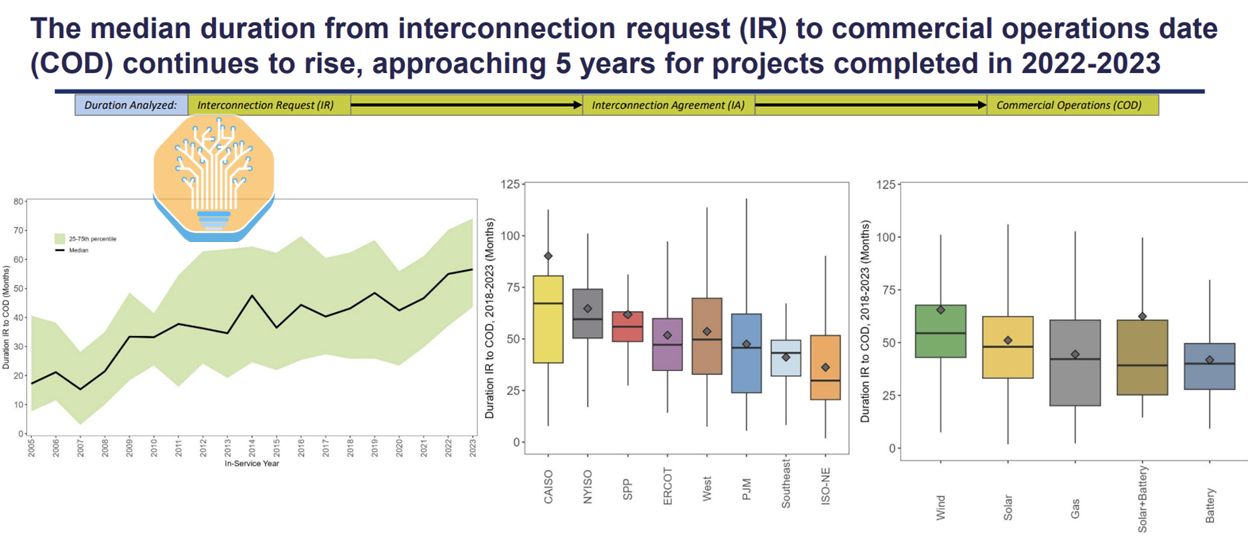

The supply side is equally constrained. The timeline from interconnection request to commercial operation now stretches to five years for most generation types.

AI infrastructure developers cannot wait five years. In many cases, they cannot wait six months, because waiting six months costs billions of dollars of lost opportunities.

Enter BYOG - Bring Your Own Generation

The core value proposition of BYOG is simple: start operating without waiting for the grid. A datacenter can run indefinitely on local generation, then convert that equipment to backup power once grid service eventually arrives.

That’s exactly xAI’s strategy. They built Colossus using mobile gas turbines, bringing the facility online in months rather than years. Now everyone is following the playbook.

Let’s examine how.

How to Bring Your Own Generation

The Old World vs The New World

BYOG involves a complete re-thinking of the way we build power plants. Traditionally, we deliver power via large, centralized GW-scale baseload generators – accompanied by smaller peaker plants to handle spikes in grid-wide load. Heavy-duty gas turbines in combined cycle mode are the most common modern deployment. Their unmatched fuel efficiency (>60%) provides the backbone of our modern civilization. However, their main issue is deployment speed:

There is typically a multi-year lead time to get large turbines, and current lead times are at an all-time high.

Once delivered, construction and commissioning of a large combined-cycle power plant takes ~2 years - an eternity in the AI era.

AI Datacenter “BYOG” power plants re-shape the playbook, and xAI led the way for the industry. To deploy faster, Elon’s AI Lab relied on small modular 16MW turbines from Solar Turbines, a CAT subsidiary. The turbines are small enough to be transported by standard long-haul trucks. They’re deployed in a matter of weeks. Elon didn’t even buy them – he rented from Solaris Energy Infrastructure to bypass the equipment lead time. He also leveraged VoltaGrid’s fleet of mobile truck-mounted gas engines to deliver faster!

Other hyperscalers quickly followed suit. Meta’s deployment in Ohio, with Williams, is illustrative – with their power plant comprising five different types of turbines & engines, clearly the design pattern was “I’ll deploy whatever I can get on time!”

Let’s now dig into the different types of equipment available to datacenter operators.

Equipment Landscape Overview

Among gas generators available to datacenter developers, there are three broad categories:

Gas Turbines (GTs) - low-temp, slow-to-ramp industrial gas turbines (IGTs); high-temp, fast-to-ramp aeroderivative gas turbines (Aeros); very large heavy-duty gas turbines.

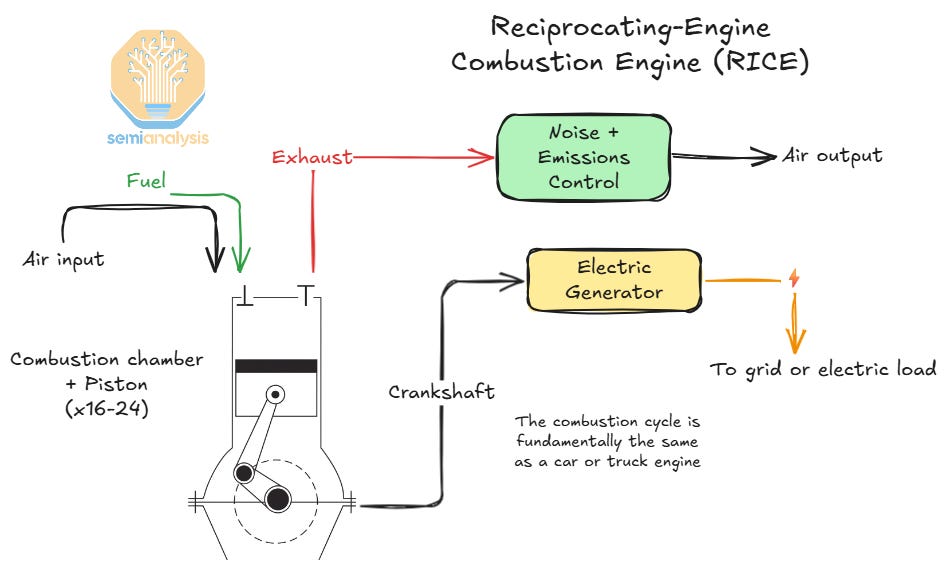

Reciprocating Internal Combustion Engines (RICEs) - both smaller, 3-7 MW high-speed engines; and larger, 10-20 MW medium-speed engines. Sometimes called “recips” for short.

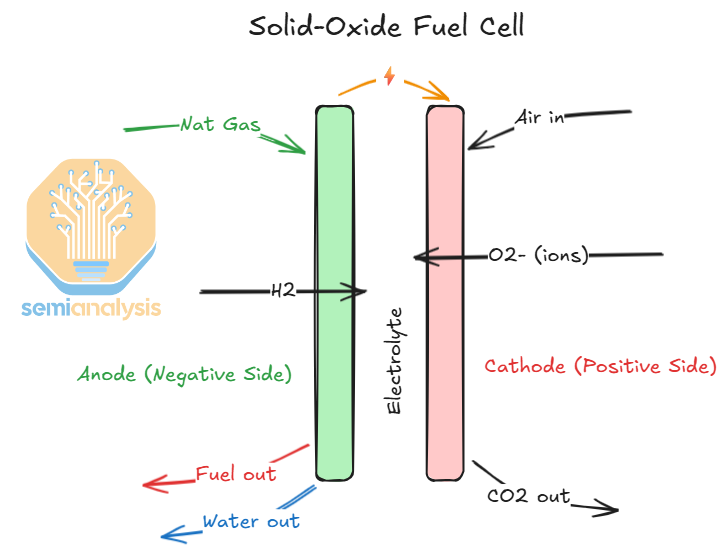

Solid-oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) - the main option available so far is from Bloom Energy.

There are additional onsite power options such as co-locating with an existing nuclear power plant, building onsite SMRs, Geothermal, and many more, but we won’t discuss them in this report. For the most part, these other solutions are not driving net new power generation in the next ~3 years.

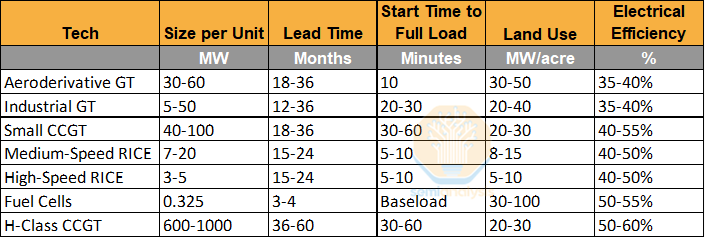

Understanding which solutions are the best fit for certain use-cases requires digging into the core tradeoffs. We see the following as most relevant:

Cost: Usually listed as $/kW. These cost estimates vary wildly and are consistently rising across every generator category. Note that maintenance expenses are also relevant: certain systems have lower useful life, i.e. higher annual maintenance costs.

Lead Time (shipment and installation): Usually listed in months or years. Lead times are increasing across every generator category as demand growth outstrips supply.

Note that other factors outside generator availability can affect time-to-power. Most notably, air permitting for onsite generation can take a year or more, even in fast-to-permit states like Texas.

In addition, installation time varies widely across systems. Some can take barely a few weeks from delivery onsite to power generation, such as small truck-mounted turbines or engines, as well as fuel cells. Large CCGTs can take over 24 months to assemble.

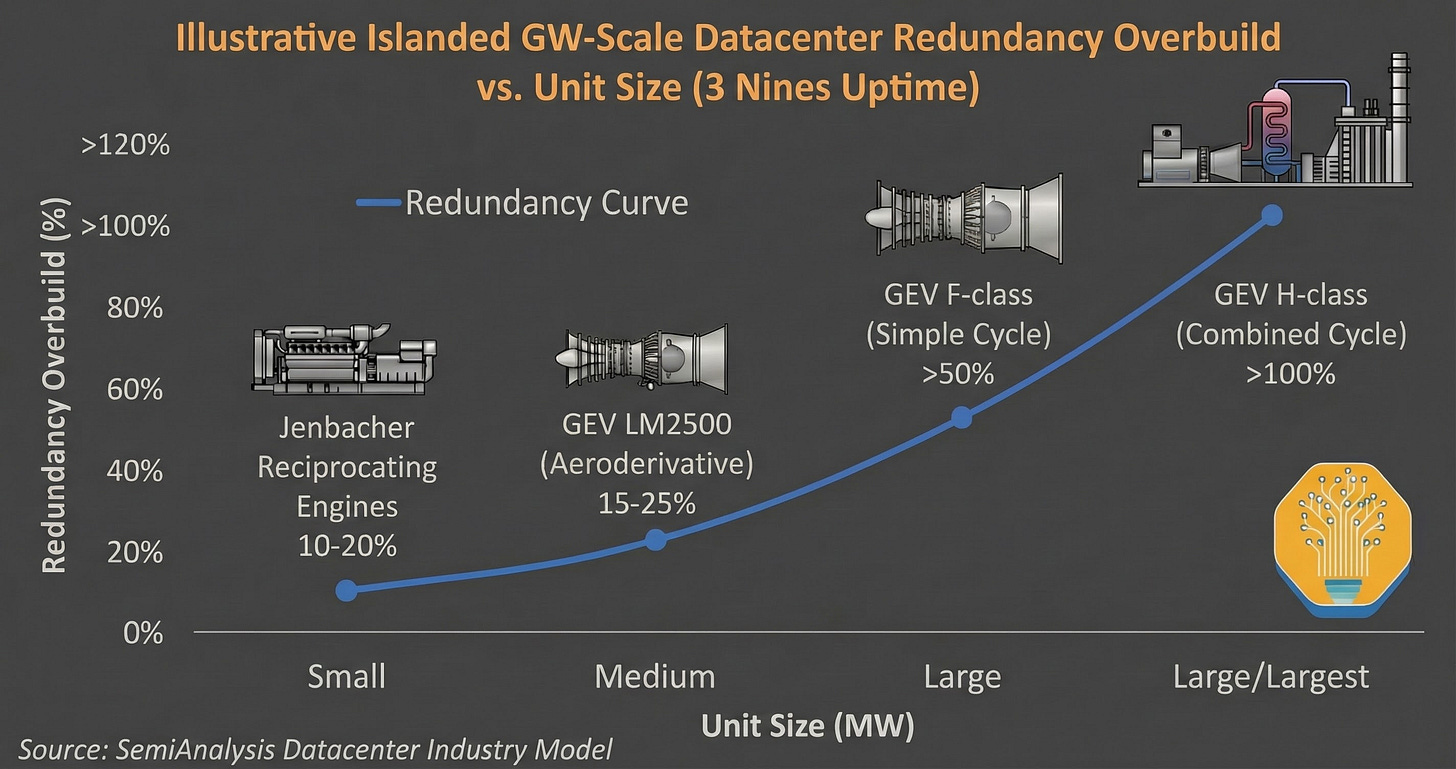

Redundancy & uptime: the expected availability of the generator, expressed in % of uptime over a year, or in “nines” of uptime. The US Electric grid averages 99.93% (3 nines) over the last ten years, with some areas even higher. For an onsite power plant, redundancy can be managed by adding hot spares and cold spares, or by having additional backup power. The larger the individual turbines, the more difficult managing spares & backup is.

Ramp Rate: Measured as minutes between cold start and maximum output. A ramp rate of less than 10 minutes makes a generator eligible as reserve generation for an electric grid or backup power. A slow ramp-rate means that the unit is primarily focused on baseload power.

Land Use: Measured as MW/acre. This matters more in space-constrained areas. Water use for small generation systems is insubstantial, even as a fleet. However, very large turbines do require significant water use for cooling.

Heat Rate and Fuel Efficiency: Measured as BTU of natural gas per kWh. A higher heat rate means lower efficiency—more fuel in, same electricity out, more waste left behind. Nameplate heat rate assumes “peak” operating conditions, typically maximum output. Efficiency drops substantially below 50% output.

Many of these onsite gas systems can be configured as combined heat and power (CHP) systems. For datacenters, this would entail using the waste heat from a gas generator for an absorption cooling system, allowing for reduced electricity use in cooling the datacenter.

In reality, we observe that whoever has an open orderbook and can provide good timelines tends to win deals, regardless of most other specs!

Having said that, let’s now deep dive into the different types of gas power plants.

Aeroderivatives and IGTs – highly attractive for datacenters

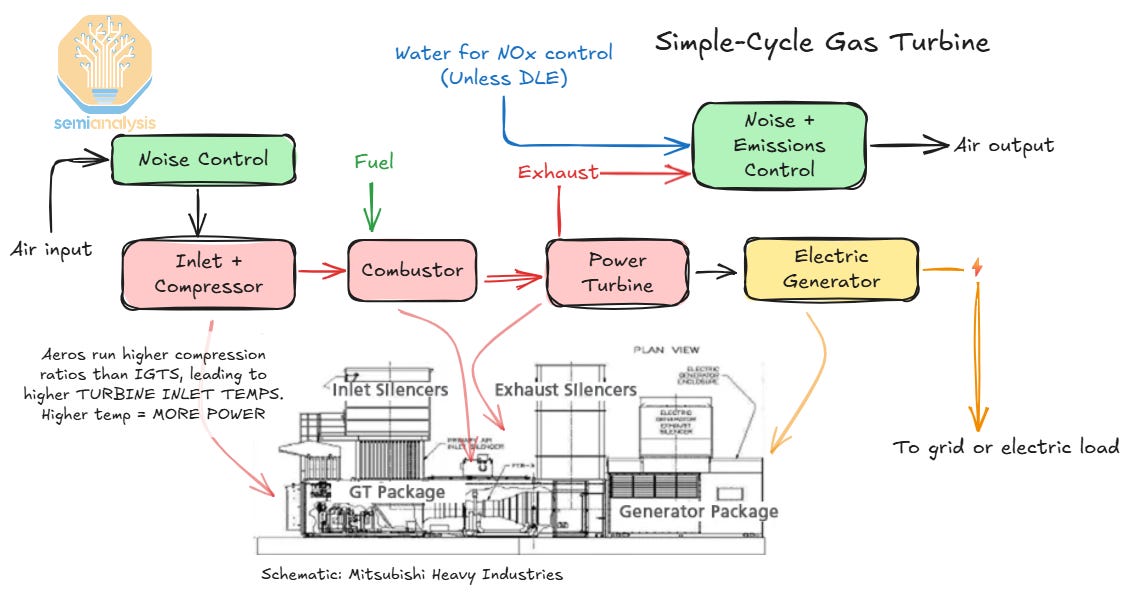

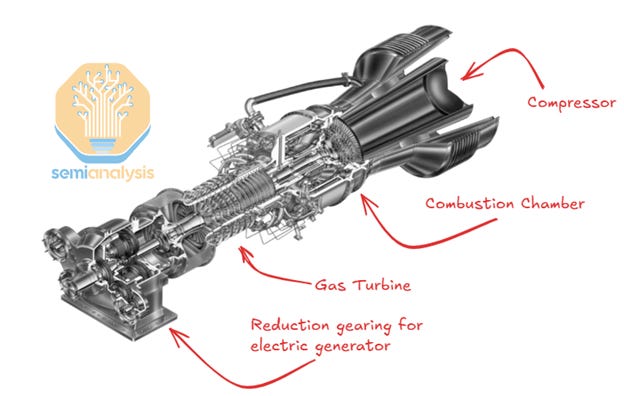

Gas turbines run on a Brayton Cycle: compress air, burn fuel in it, and route the hot gas through a turbine. Turbines are differentiated by inlet temperatures. Lower temperatures correspond to lower installation costs, lower maintenance costs, lower peak efficiency, and slower ramp rates.

An aeroderivative gas turbine is simply a jet engine bolted to the ground. GE Vernova’s aeros derive from GE jet engines; Mitsubishi Power’s from Pratt & Whitney; Siemens Energy’s from Rolls-Royce. Because jet engines are designed to deliver massive power in a compact, flight-worthy package, they are relatively easy to adapt for stationary power. Extend the turbine shaft, bolt a generator coil to the end, add intake and exhaust mufflers, and feed fuel from tanks or a pipeline. This is, in part, why Boom Supersonic could pivot so quickly into aeroderivative gas turbines: most of their engineering and manufacturing is carryover.

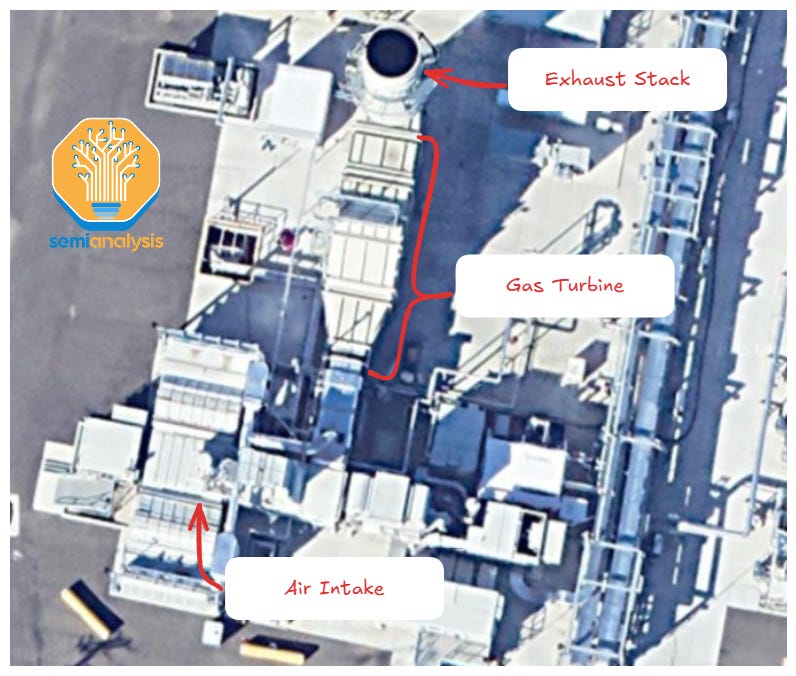

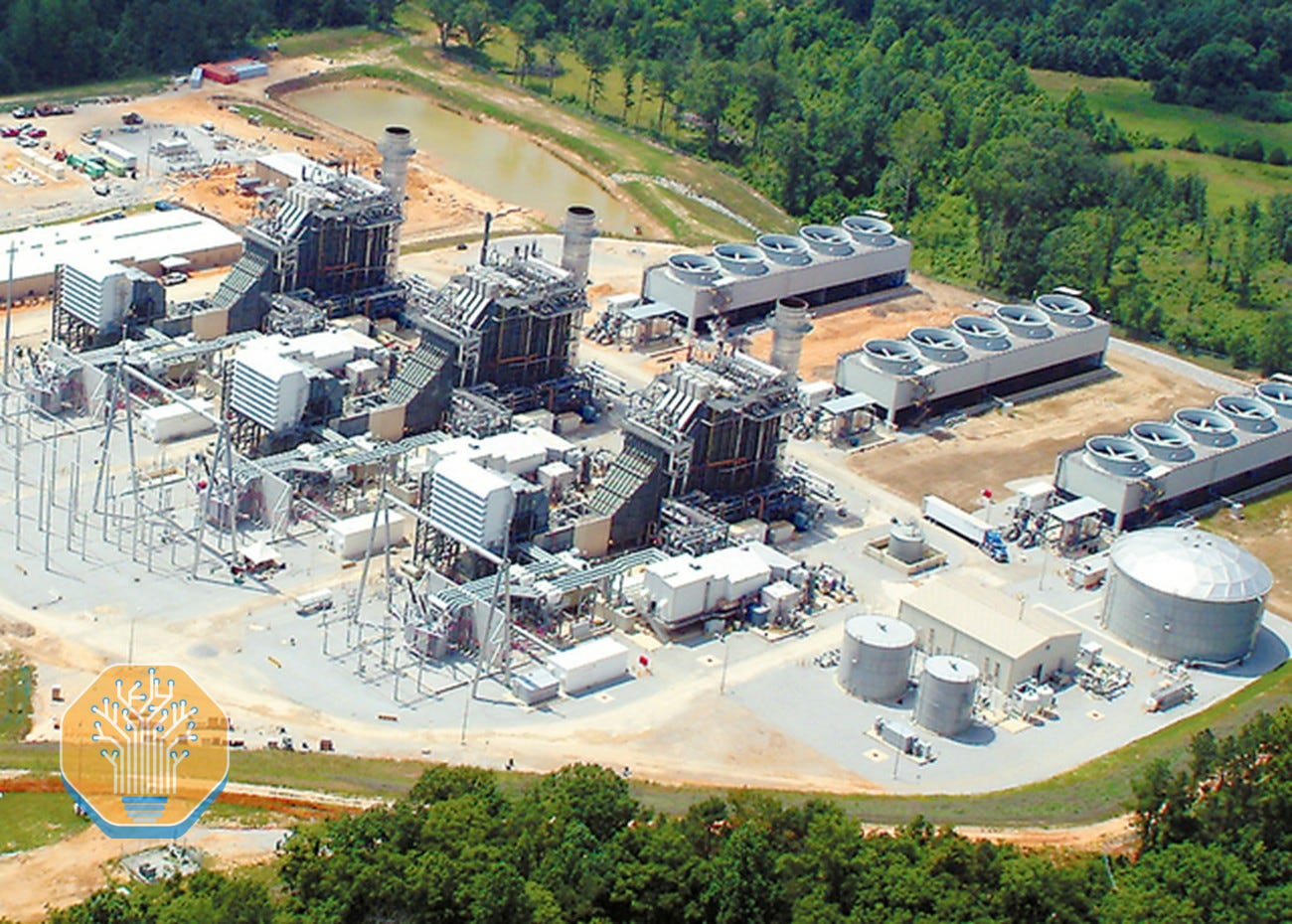

We show below a view of the Martin Drake power plant, w/ 6x GE Vernova LM2500XPRESS units. This is how electric utilities deploy aeroderivatives, as “peaker plants” for sudden supply shortages in the grid.

The core manufacturers for aeroderivative gas turbines are similar to those of heavy-duty gas turbines: GE Vernova, Mitsubishi Power, and Siemens Energy dominate the market, selling both aeros and lower-temp industrial gas turbines (IGTs). Additionally Caterpillar also produces IGTs under the Solar brand name, as does Everllence (formerly MAN Energy Systems).

Two GE Vernova designs dominate the aeroderivative market:

LM2500 – ~34 MW, optimized for fast deployment, especially as LM2500XPRESS.

LM6000 – ~57 MW, now available in fast-deploy LM6000VELOX configurations.

Aeros are reasonably efficient with fuel but extremely efficient with respect to space and weight. They can fit in tight footprints, and in some configurations can be transported on a pair of tractor trailers. Simple-cycle aeros typically come in 30-60 MW packages and can ramp from cold to full output in 5-10 minutes. However, efficiency suffers if they are at less than full steady load. Aeros can also be configured as small combined-cycle plants:

1x1 (one combustion turbine feeding one steam turbine), or

2x1 (two combustion turbines feeding one steam turbine).

These combined-cycle setups deliver higher efficiency and more output at the cost of ramp speed. Startup times lengthen to 30–60 minutes.

At current rates, aeros cost $1,700-2,000/kW in all-in capital expenditure, and based on recent orders, they have lead times of 18-36 months and rising. Smaller turbines can have lead times as short as 12 months, and larger aeros (~50 MW) can take up to 36 months. These systems are quick to install (2-4 weeks usually), but the factories are heavily booked. One workaround is truck-mounted turbines, which can be rented and deployed quickly, if available. xAI used this exact strategy, partnering with Solaris Energy Infrastructure to shrink their time-to-power for Colossus 1 and 2.

Industrial Gas Turbines (IGTs)

Industrial gas turbines work on the same cycle as aeros and share benefits like compact footprints, modularity, and relatively fast lead times. But they are designed from scratch for stationary use rather than adapted from aviation. They typically run at lower inlet temperatures and use simpler designs, which lowers service costs at the expense of efficiency and ramp speed.

Simple-cycle IGTs span roughly 5–50 MW and ramp from cold to full output in ~20 minutes. That makes them too slow, on their own, to serve as peaker plants or emergency backup without help from batteries or diesel units. Like aeros, IGTs can be upgraded to combined-cycle configurations, improving efficiency while further slowing ramp rate.

The most common dedicated industrial gas turbines are the Siemens Energy SGT-800 and Solar Titan Series. However, smaller heavy-duty gas turbines like the GE Vernova 6B also sometimes take on similar use cases.

At current rates, IGTs cost $1,500-1,800/kW in all-in capital expenditure, with lead times of approximately 12-36 months, similar to aeros. However, procuring a used or refurbished IGT can shrink lead times to under 12 months, which is how Fermi America is procuring power.

Overall, we believe that aeroderivatives and IGTs are a very attractive solution for onsite power generation, because:

They are the “right” size: small enough to facilitate redundancy, large enough to avoid having too many units onsite and complexifying maintenance.

They have a fast ramp-rate: while they aren’t as energy-efficient as others, they can more easily be repurposed for backup power.

They are quick to deploy, normal trucks and construction crews can transport and install them, instead of the insane heavy-lift infrastructure necessary for heavy-duty turbines.

We’ll discuss these concepts later in the report when discussing deployment considerations. The main issue with aeros and IGTs is, increasingly, lead times.

The most supply-constrained component in gas turbines are the turbine blades and cores, which must handle high temperatures and speeds. These blades use exotic monocrystalline nickel alloys that include rare-earth metals like rhenium, cobalt, tantalum, tungsten, and yttrium. Notably, yttrium is among the rare earths under export control from the Chinese government. The cores, meanwhile, require high-temperature ceramics that are in short supply.

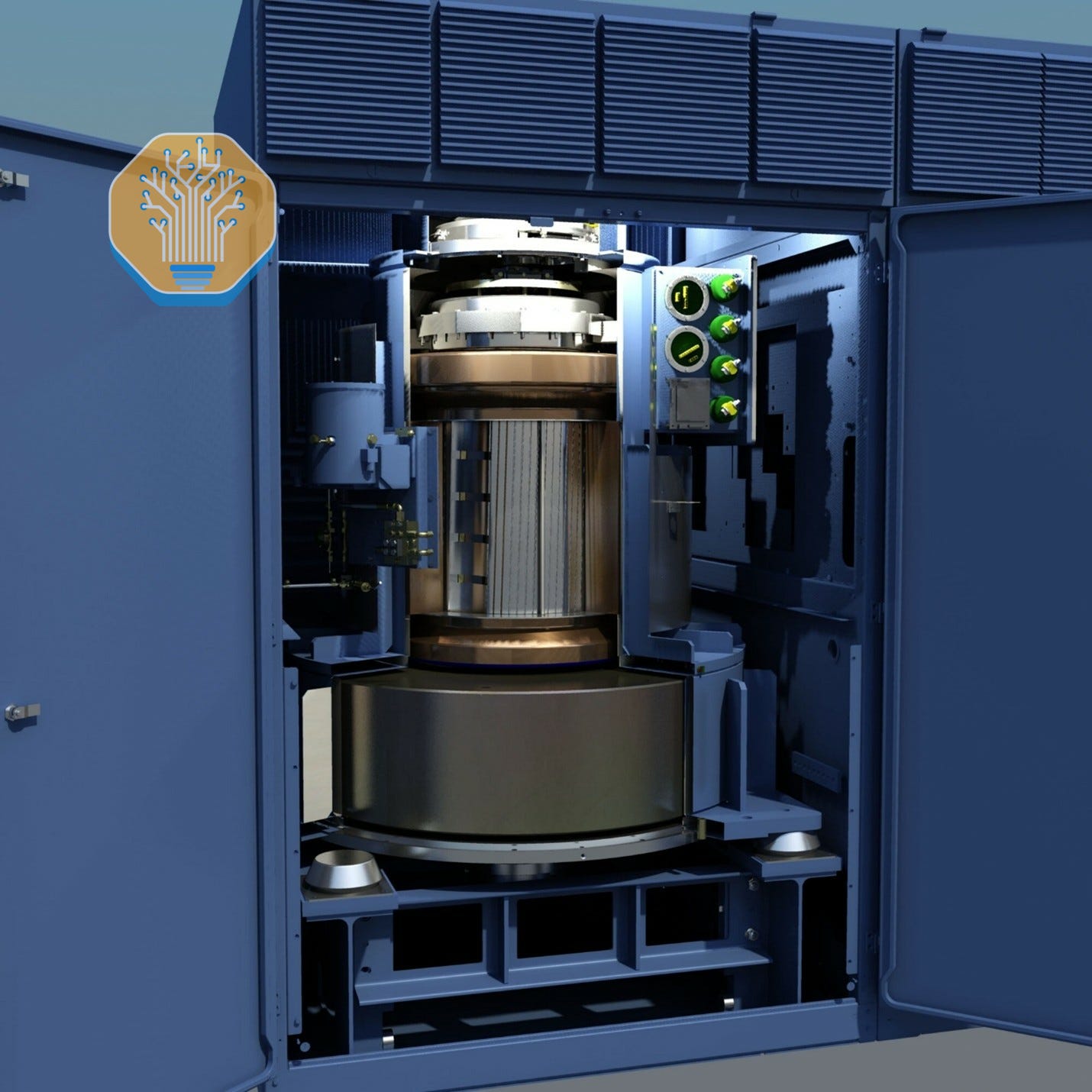

Reciprocating Engines (RICE)

Reciprocating engines function like automotive engines, but at a much larger scale, an 11MW engine can be more than 45 feet (14 m) long. They use four-stroke combustion cycles and are divided by rotation speed:

High-speed engines – ~1,500 rpm; smaller in footprint and output.

Medium-speed engines – ~750 rpm; generally lower maintenance costs due to lower mechanical stress.

RICEs can ramp from cold to full output in 10 minutes, similar to aeros in practice. This lets RICEs work as peaker plants or as backup generators, eliminating the need for diesel backups. On paper, RICE O&M looks higher than for turbines because there are more moving parts. In practice, they handle fuel impurities, dust, and high ambient temperatures better than many turbines and suffer less de-rating in hot climates.

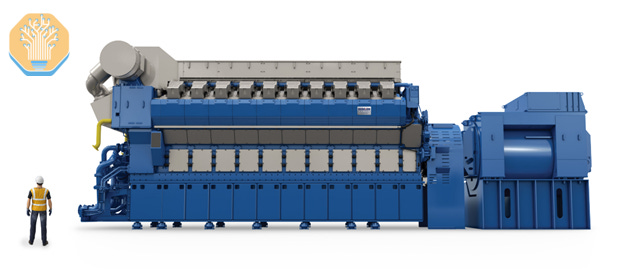

Medium-speed engine manufacturing is fairly consolidated, with the primary manufacturers being Wärtsilä, Bergen Engines, and Everllence (formerly MAN Energy).

High-speed engine manufacturing is not as consolidated as turbines. Outside the prominent players in Jenbacher, CAT, Cummins, and Rolls Royce subsidiary MTU, there are a wide range of manufacturers, because high-speed gas engines are functionally equivalent to the diesel engine designs currently used for backup power at many datacenters. The most consequential reciprocating engine is the Jenbacher J624, a 4.5MW turbocharged gas engine that can be containerized for easier logistics. This system is the preferred generator for VoltaGrid’s energy integration services.

RICE systems typically generate less power per unit than equivalent turbines. Medium-speed engines run between 7 MW and 20 MW, with the higher power outputs enabled by turbocharging. High-speed engines are even smaller, with per-unit outputs between 3 MW and 5 MW. However, RICE generators are more efficient than turbines when running at partial loads between 50% and 80%.

Reciprocating engines operate at much lower temperatures than gas turbines, closer to 600°-700°C. This dramatically reduces their need for high-performance alloys. Only the high-temperature components in the pistons, combustion chambers, and turbochargers still need rare nickel and cobalt alloys, and the rest can be manufactured with simple cast iron, steel, and aluminum. However, RICEs overall are less dependent on critical minerals, especially if emissions controls are relaxed during a materials supply crunch.

At current rates, reciprocating engines cost $1,700-2,000/kW in all-in capital expenditure and have lead times of 15-24 months. Compared to turbines, these systems are less delayed in manufacturing; the manufacturing timeline is closer to 12-18 months. However, medium-speed RICEs are considerably heavier than turbines, and installation and commissioning can take up to ~10 months.

High-speed engines can be much faster to deploy. For example, at the initial Colossus 1 deployment, xAI leveraged 34 VoltaGrid truck-mounted systems, incorporating high-speed engines from Jembacher. High-speed engines, in particular, are popular with energy procurement vendors (described later). Their wide availability and small unit size offer faster time-to-power. We show below a VoltaGrid 50MW deployment in San Antonio, with twenty Jembacher J620 (rated 3.36kW per unit).

The tradeoff is scale: to build a 2 GW onsite gas system with 5 MW engines, you need 500 units! That has major operational consequences. If each engine needs minor servicing every 2,000 hours, the maintenance staff would perform more than 2,000 services per year, almost 40 per week. These costs are more predictable than turbine overhauls (which can involve swapping entire cores), but they add up, especially for fleets with many small units. Space and spares inventories grow similarly, although vertical stacking of small generators can mitigate land use, a trick not available for medium-speed engines.

Fuel cells and Bloom Energy’s ascent

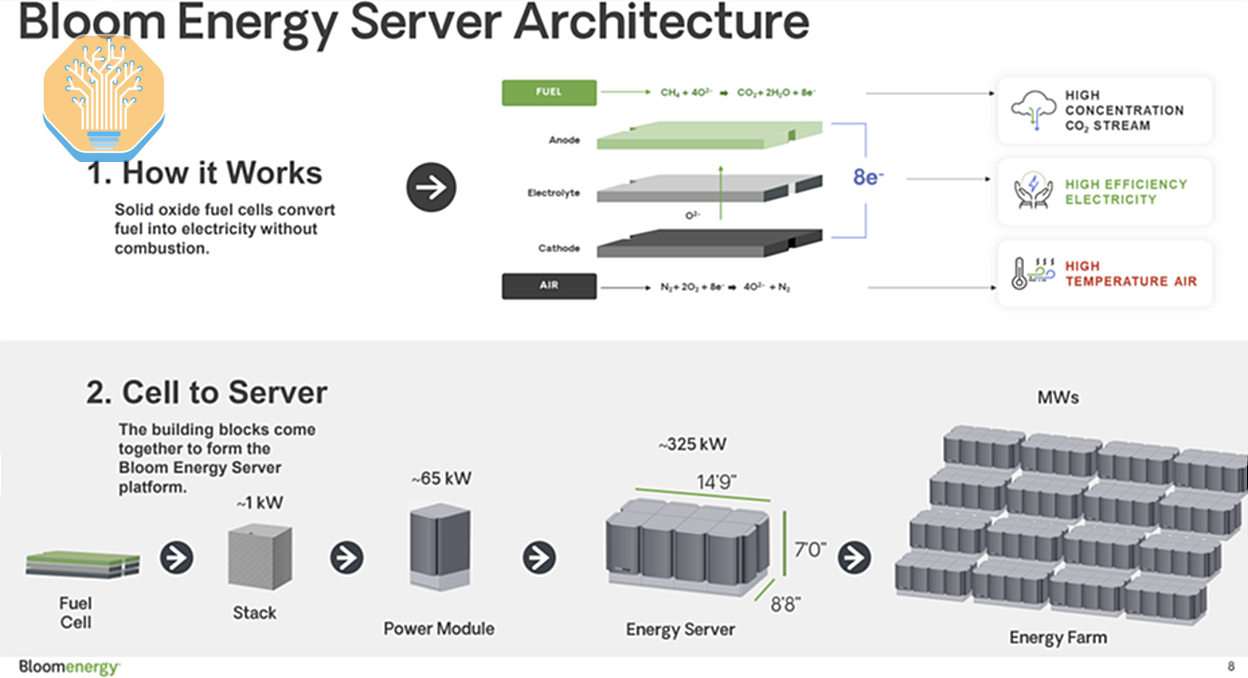

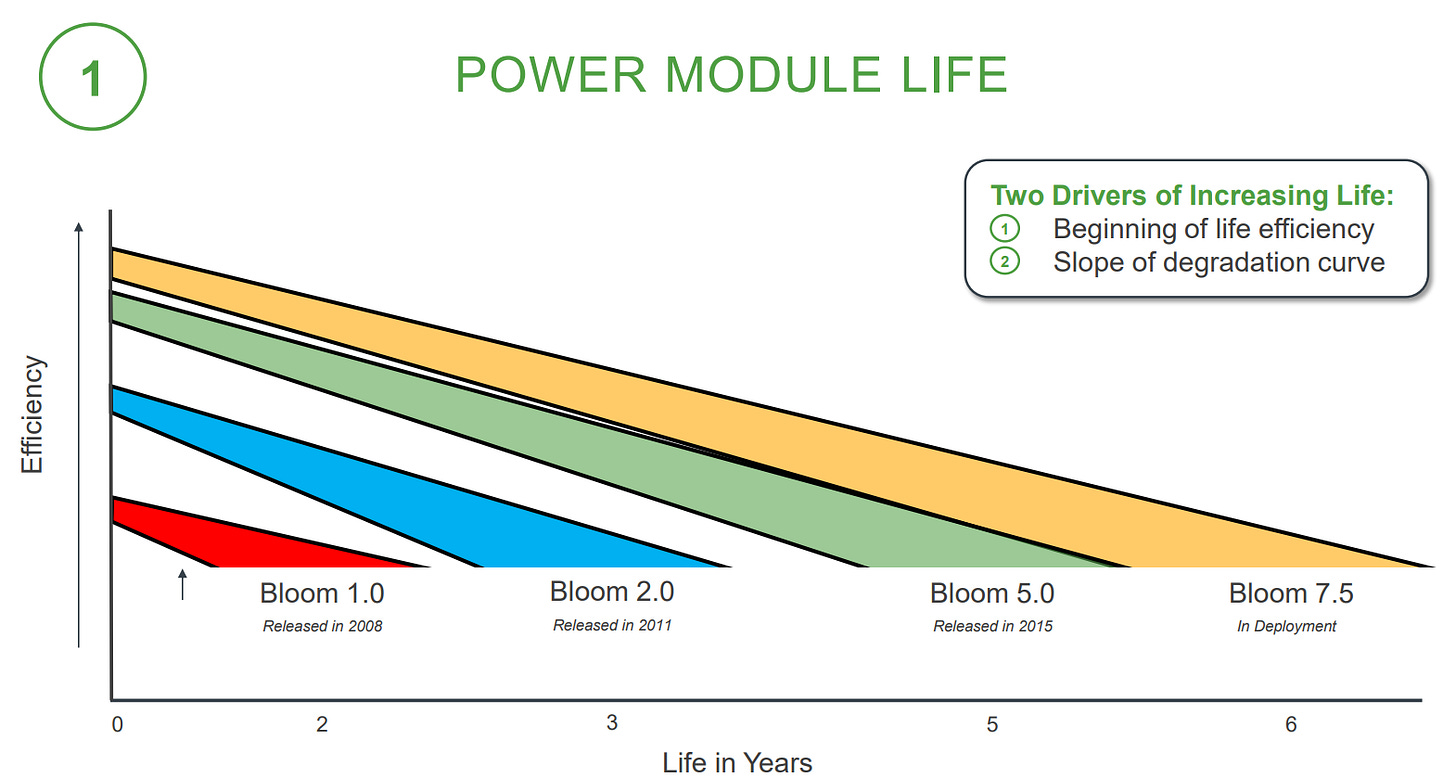

A fairly niche solution is now taking an increasingly large share of the pie: fuel cells. Often associated with hydrogen, Bloom Energy’s SOFC fuel cells can run on natural gas too and are pitched as baseload generation. We first called out Bloom Energy as a big winner in last 2024 in the datacenter model. Since then the orders have skyrocketed.

Bloom’s “Energy Server” is made up multiple ~1kW stacks, assembled into ~65kW modules, and packaged into a 325kW power generator. To date, the largest operational SOFC-based power plants are in the tens of MW, mostly in the US and Korea.

The way they generate energy is very different from that of traditional generators. There is no combustion process. Instead, oxygen is electrochemically reduced to oxide ions, which flows through a ceramic electrolyte. At the other end of the fuel cell, these ions combine with hydrogen atoms stripped from methane natural gas. This combination releases water, CO2, and electricity.

This fundamental difference provides Bloom’s fuel cells with a key advantage: they do NOT generate material air pollution, besides CO2. The permitting at the EPA level is significantly smoother and easier than that of combustion generators. That’s why we often see them in population centers, such as near offices.

Bloom’s killer feature is the speed of deployment. It barely requires precast pads and a simple installation of modules. Once factoring-in the electrical work, installation & commissioning can be done in a matter of weeks, matching the speed of aeroderivatives and high-speed RICE.

In the AI era where speed is the moat, that advantage alone is enough to place Bloom on the map.

Bloom’s main challenge is cost. Fuel cell efficiency is quite good, with an equivalent heat rate of 6,000-7,000 BTU/kWh, which is on-par with CCGTs. However, the costs for fuel cell systems are notably higher than turbines or RICE systems, at a capex cost between $3,000-$4,000/kW. Bloom does not advertise ramp rates, suggesting these units are too slow to function as peakers or emergency backup.

Maintenance has historically also been notably higher than other solutions. Individual fuel cell stacks last roughly 5-6 years, then must be replaced and refurbished. This per-cell replacement makes up ~65% of service costs, although specific numbers are kept close to vest. Bloom discloses little about its materials beyond the use of ceramics in the cell core, but claim that their fuel cells have no critical mineral dependence on China or other contested regions.

We provide TCO estimates for Bloom fuel cells behind the paywall.

Heavy-duty gas turbines: the future of BYOG?

Before ChatGPT, only utilities and independent power producers (IPPs) had any reason to buy a gas turbine larger than 250 MW, because turbines above that threshold are simply too large to use for most industrial applications. As explained above, speed of deployment is an issue, however, we’re increasingly seeing developers provide “bridge power” via smaller aeroderivatives/RICE then shift them as backup/redundancy once the big CCGT is operational.

Large turbines are grouped into classes based on combustion (turbine inlet) temperature and technology stack:

E-Class and F-Class – Older, lower-temperature, lower-efficiency designs. Some F-class units are still sold, usually into developing markets, because they offer decent efficiency at lower capex. The line between “industrial” turbines and small E/F-class frames is fuzzy, with the below famous models straddling that boundary:

GE Vernova 6B

GE Vernova 7E

Siemens Energy SGT6-2000E

H-Class and equivalents – Modern, high-temperature designs. These run firing temperatures comparable to modern aeros and jet engines, but with roughly 10x the per-unit power. The most prominent examples are:

GE Vernova HA series (e.g., HA.02)

Siemens Energy H/HL

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries J series (e.g., H510J)

More recently, Korean firm Doosan Enerbility has started production of a new H-class turbine, the DGT6. It’s rare to see new entrants in a decade-old market, but Doosan has deep experience in steam turbine production and a track record of building Mitsubishi-designed F-class turbines.

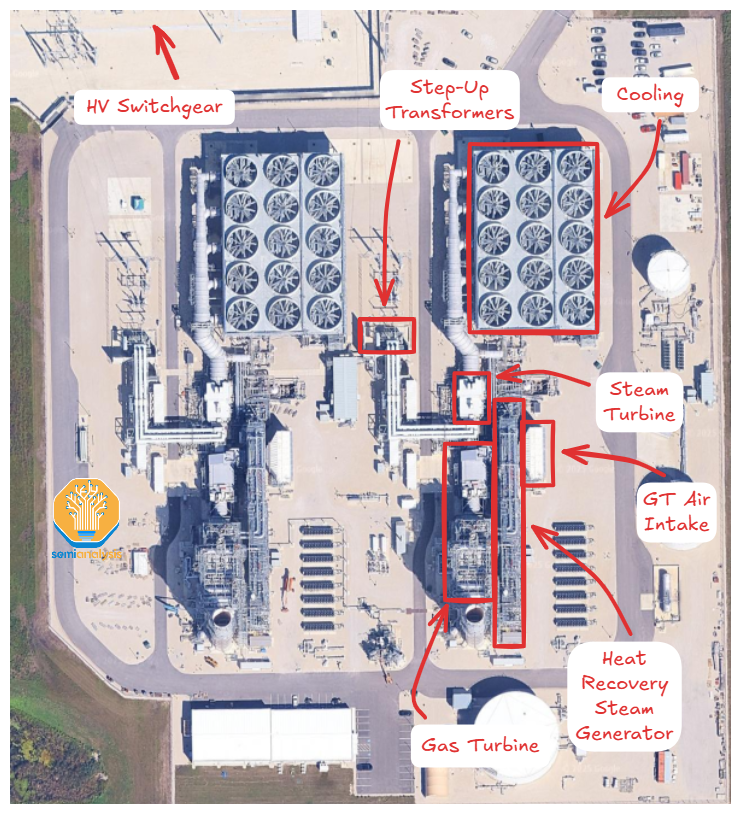

As shown below, these systems are both very large and heavy. The installation and commissioning process can take a while.

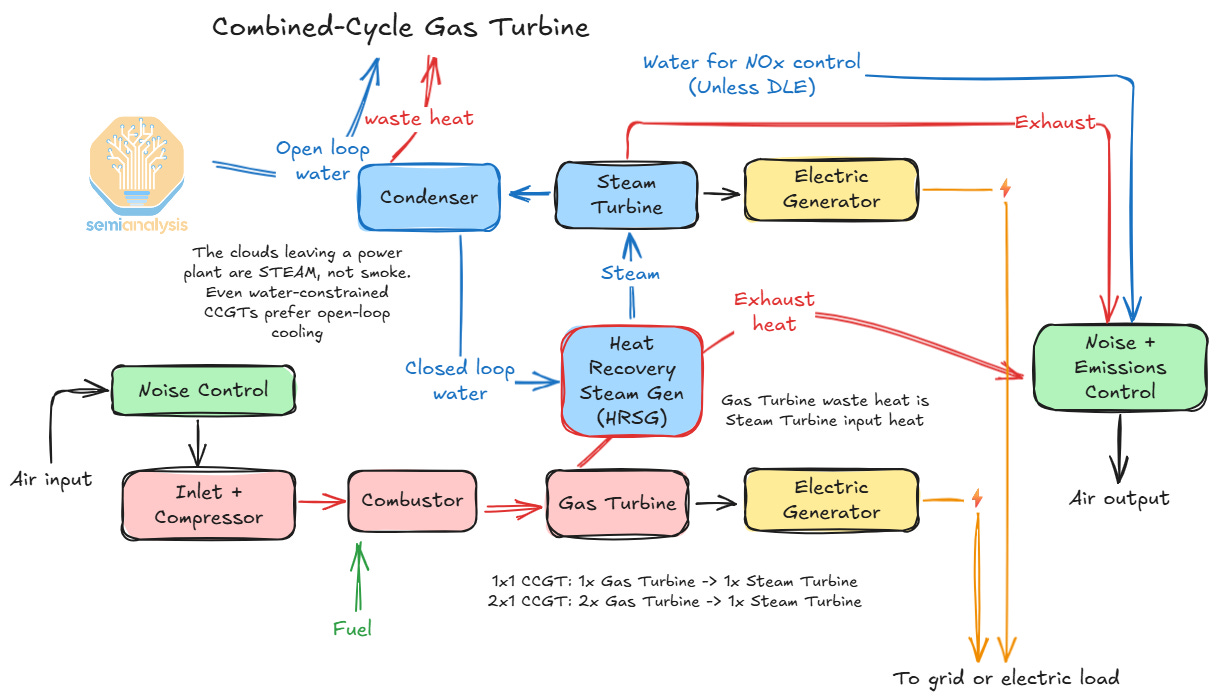

Combined-Cycle Gas Turbines (CCGTs)

Combined-cycle gas turbines (CCGTs) exploit the fact that simple-cycle exhaust is still very hot, hot enough to boil water into steam. Routing exhaust through a heat recovery steam generator (HRSG) produces steam for a separate steam turbine and generator. The result is a second round of power from the same fuel. By turning one turbine’s trash into another turbine’s treasure, CCGTs can run 50-80% more efficiently than a simple-cycle turbine.

The CCGTs most vaunted for large loads are heavy-duty CCGTs, which can reach gigawatt-scale outputs. However, even small aeroderivative or industrial gas turbines can be sold with an integrated steam turbine, which can dramatically increase power output with near-identical fuel inputs. Common configurations are:

1x1 – One gas turbine feeding one steam turbine

2x1 – Two gas turbines feeding one steam turbine

In theory, more gas turbines can feed a single steam turbine but returns diminish. The primary drawback of a CCGT system is the ramp rate: the addition of the steam turbine slows the time from cold start to full output to 30 minutes or more.

The other major drawback is the lead time. Installation & commissioning is even longer than for a simple cycle deployment.

From equipment to execution: deployment, challenges, economics

Understanding the equipment landscape is necessary but not sufficient. The real complexity in onsite gas isn’t choosing between an LM2500 and a Jenbacher J624—it’s figuring out how to configure, deploy, and operate these systems to meet datacenter uptime requirements.

The electric grid is a marvel of systems engineering: thousands of generators, hundreds of transmission lines, and sophisticated market mechanisms that together deliver 99.93% average uptime. When you go off-grid, you’re taking on that complexity yourself—with a single plant that has to match grid-level reliability. Redundancy and uptime are the key reason why onsite gas power costs are, in most cases, structurally much more expensive than power delivered by the grid.

The next section examines how leading deployments are solving this challenge, and what it means for equipment selection.

Crusoe and xAI: bridge power deployment

One of the most popular onsite gas strategies so far has been “bridge power”. The datacenter campuses have an active discussion with the grid to get electrical service, but begin operations before via onsite power.

Bridge power clears electricity as a bottleneck to operation, allowing a datacenter to start training models or generating revenue several months earlier. This speedup is significant! AI cloud revenue can net $10-12M per MW annually, meaning that getting 200 MW of datacenter powered and online even six months earlier can net $1-1.2 billion in revenue.

Bridge power brings two advantages:

The uptime requirements can be matched to the workload. For example, in Abilene TX and Memphis TN, both xAI and Crusoe/OpenAI are deploying large training clusters. Training jobs don’t need particularly elevated uptime, given the inherent unreliability of large GPU clusters. As such, “overbuilding” the power plant for redundancy can be avoided. Once a grid connection is secured, the campus can be more fungible and also used for inference.

Favorable economics via removal of diesel generator backup. In both Memphis and Abilene, the absence of backup reduces datacenter capex/MW. Once a grid connection is secured, the turbines can act as backup – as such, fast ramp-rate systems are preferred, e.g. aeroderivatives.

To ensure reasonable uptime, xAI paired the turbines with MegaPacks. That also enables to smooth out load fluctuations – an issue we’ll discuss below.

Staying Off-Grid Forever: redundancy challenges, Energy-as-a-Service

Many generator vendors suggest that datacenter owners should never bother interconnecting with the broader electric grid; instead, they argue that their datacenter customers should stay off-grid forever. Firms like VoltaGrid offer a full “Energy-as-a-Service” package managing all aspects of electric service:

Electric energy – MW of capacity and MWh of energy

Power quality – Voltage and frequency tolerances

Reliability – Targeted “nines” of uptime

Time-to-power – Months from contract to operation

They typically sign long-term PPAs with customers who pay for electric service – the EaaS vendors essentially acts as a utility. They procure equipment, design the deployment, sometimes assemble the BoM, and maintain & operate the power plant.

A key challenge when deploying off-grid generation is managing redundancy. For example, the 1.4GW Vantage DC campus in Shackelford County, TX will deploy 2.3GW of VoltaGrid systems. These systems being small facilitates redundancy – but if you were to deploy onsite power with large heavy duty turbines, redundancy might be to simply have two power plants, if not more.

Generation vendors will suggest at minimum an N+1 configuration, if not an N+1+1 configuration. An N+1 configuration maintains full generation capacity even if one generator unexpectedly shuts down, whereas an N+1+1 configuration enables this flexibility while also keeping another generator on standby to enable maintenance cycles. It’s the equivalent of driving a car with a spare tire and a tire repair kit. Note that N+1 or N+1+1 does not necessarily refer to a literal count of generators, given that datacenter loads are typically much larger than individual onsite gas generators. For example, consider a datacenter with an all-in (IT + non-IT) power demand of 200 MW:

Example 1: 11-MW RICEs

Generation fleet: 26 × 11 MW RICE units

Total capacity: 286 MW

Under normal operation:

23 engines run at ~80% load to produce 200+ MW.

One generator failure: 22 engines ramp modestly to ~82% load.

3 spare engines remain for maintenance or as cold standby.

Running engines below full load reduces O&M, and the extra units provide a buffer for maintenance scheduling.

Nexus Datacenter is using a similar approach: they have recently applied for an air permit for a fleet of thirty Everllence 18V51/60G gas engines, each good for 20.4 MW, for a total of 613 MW of generation. This site will also include 152 MW of diesel backup generation, which likely fulfills the N+1 redundancy requirements for the total site.

Example 2: 30-MW Aeroderivatives

Generation fleet: 9 × 30 MW aeros

Total capacity: 270 MW

Under normal operation:

7 turbines run at ~95% load for best efficiency.

One turbine failure: the 8th turbine starts, maintaining output.

The 9th turbine remains in reserve for maintenance.

Because turbine overhauls are more disruptive than engine maintenance, some vendors offer hot-swap programs: a turbine due for major service is swapped out for a replacement core.

In hot climates, such as the American Southwest, derating may require 10–11 aeros to maintain N+1+1 redundancy.

Crusoe’s Abilene site for Oracle and OpenAI uses a version of this setup, with a deployed fleet of ten turbines, with five GE Vernova LM2500XPRESS aeroderivative gas turbines and five Titan 350, good for 360MW of nameplate generation.

Example 3: Meta + Williams Socrates South

Meta and Williams are building a pair of 200 MW behind-the-meter gas plants to power Meta’s New Albany Hub, which we have covered in this article: Meta’s new ultra-fast “tent” datacenters in Ohio – SemiAnalysis

The Socrates South project is a hybrid fleet:

3 × Solar Titan 250 IGTs (23 MW)

9 × Solar Titan 130 IGTs (16.5 MW)

3 × Siemens SGT-400 IGTs (14.3 MW)

15 × Caterpillar 3520 fast-start engines (3.1 MW)

Nameplate capacity inside the fence is 306 MW: roughly 260 MW from turbines and 46 MW from engines. Under normal conditions, a subset of IGTs runs steadily to deliver 200 MW. If one or two IGTs trip, the RICE fleet can ramp quickly to cover the gap. Additional IGTs remain available for maintenance switchover. This supports an N+1+1 behind-the-meter design.

However, this is a patchwork implementation compared to the first two examples. The turbines don’t match, and the engines used are smaller, 1800-rpm high-speed gas engines. This suggests that Williams prioritized time-to-power over standardized maintenance schedules.

Match the grid’s uptime: Overbuild, Grid-as-backup, Batteries

To match the “three nines” of uptime provided by the grid, an onsite power plant must be “overbuilt” for redundancy. This is typically the key reason for higher onsite generation power costs, relative to the grid.

Redundancy introduces a new headache for operators: there is a tradeoff between the size of a system and the “overbuild” ratio. While H class and F class turbines are more energy-efficient than aeros, the higher redundancy needs means than, if poorly designed, an islanded system based on heavy duty turbines can yield higher power costs than aeros. Other solutions than a simple “overbuild” must be considered, such as using smaller turbines as “backup”, batteries, or even a grid connection.

To understand the overbuild ratio, we can use a practical example. In Shackelford County, TX, VoltaGrid is poweing a 1.4GW datacenter (IT capacity) with 2.3GW of Jembacher systems (64% overbuild). We can break this down in the following way:

Peak PUE overbuild: as is typical for a grid-connected sites in Texas, there is a 1.4x - 1.5x over provisioning, largely related to cooling.

There is an additional 10-17% overbuild related to redundancy.

For H/F class systems, a simple overbuild is often not the most economical path. Some operators are considering a grid connection solely for backup purposes - but that introduces interconnection timeline challenges, and complicates the site selection process (need access to high-voltage lines). A huge battery plant can also be built - as we illustrate below with xAI’s Colossus 2 deployment - but that’s both expensive and impractical, given 2-4hrs of typical storage duration. Lastly, a combination of different sizes of turbines and engines can be used, with H-class in combined-cycle mode operating as baseload, and IGTs/aeros/RICE as backup—but that’s typically more expensive than a grid connection or a 2-4hr BESS.

Managing Load Surges

AI compute load, particularly training, is highly variable, including megawatt-scale power surges and dips on a sub-second basis. The more inertia a power system has, the better it can manage short-term power fluctuations while maintaining power frequency. If frequency deviates too far from the 50 Hz or 60 Hz baseline, the power fluctuations can trip breakers or cause malfunctions. All thermal generators have some inertia, because they are generating electricity with a spinning heavy object. However, a developer can increase inertia with auxiliary systems:

Synchronous condensers – These are essentially generators spun up as motors, with no mechanical load. Once synchronized to the grid, they consume only small losses. During sudden load changes, they absorb or supply reactive power, stabilizing voltage and adding short-duration inertia. Their energy capacity is small, so they help for seconds, not minutes.

Flywheels – These add a real rotational energy buffer. A motor-generator is coupled to a large flywheel and connected between generation and load. Flywheels can inject or absorb real power (not just reactive) for 5–30 seconds, smoothing transients, generator trips, and voltage dips. Bergen, for example, packages flywheels alongside its engines via an affiliate vendor.

Battery energy storage systems (BESS) – Batteries can ramp as quickly as the load changes, providing “synthetic inertia” through high-speed control, as described in an earlier article. They excel at frequency regulation, but because inverters are current-limited, they contribute less to reactive power and fault currents than synchronous machines.

VoltaGrid combines RICE fleets with synchronous condensers. Bergen Engines has sold engines with flywheels from a vendor under the same parent company. Engine manufacturer Wärtsilä has a battery energy storage vertical that they may bundle with datacenter projects. Bloom claims that their fuel cell systems don’t need any equipment to manage load fluctuations. The exact system used depends a bit on local constraints and mostly on what the vendor prefers to use. xAI prefers to use Tesla’s Megapacks for backup and handling load fluctuations.

Can we even build enough gas power plants to power AI?

Current lead times for gas generation systems are unprecedented. Historically, gas turbine manufacturers have only taken orders on average 20 months in advance of shipment from factories, but now the Big Three of manufacturers, GE Vernova, Siemens Energy, and Mitsubishi Power, are accepting orders into 2028 and 2029, with nonrefundable reservation slots beyond that Every public manufacturer of gas systems reports rising datacenter demand, but most are responding with caution, not a full-send buildout.

GE Vernova has promised to increase production to 24 GW/year, but that only returns them to its 2007–2016 levels. They are investing in new staff in machinery, but do not intend to increase factory footprint.

Siemens Energy also plans to invest in production without increasing factory footprint. They are instead prioritizing price increases, leaning on service revenue, and prioritizing investments with short payback periods. They plan to scale annual capacity from ~20GW to >30GW by 2028-30.

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries has guided to increase gas turbine & combined-cycle production by 30% in recent earnings calls, contrary to Bloomberg reporting about plans to double capacity by 2027.

Caterpillar plans to double engine production and 2.5x turbine production between 2024 and 2030, but their Solar-branded turbine production averaged ~600 MW/year between 2020–2024, with a 2022 peak production of 1.2 GW.

Wärtsilä has promised only incremental expansion, preferring to “wait and see” on datacenter demand and preserve relationships with marine customers.

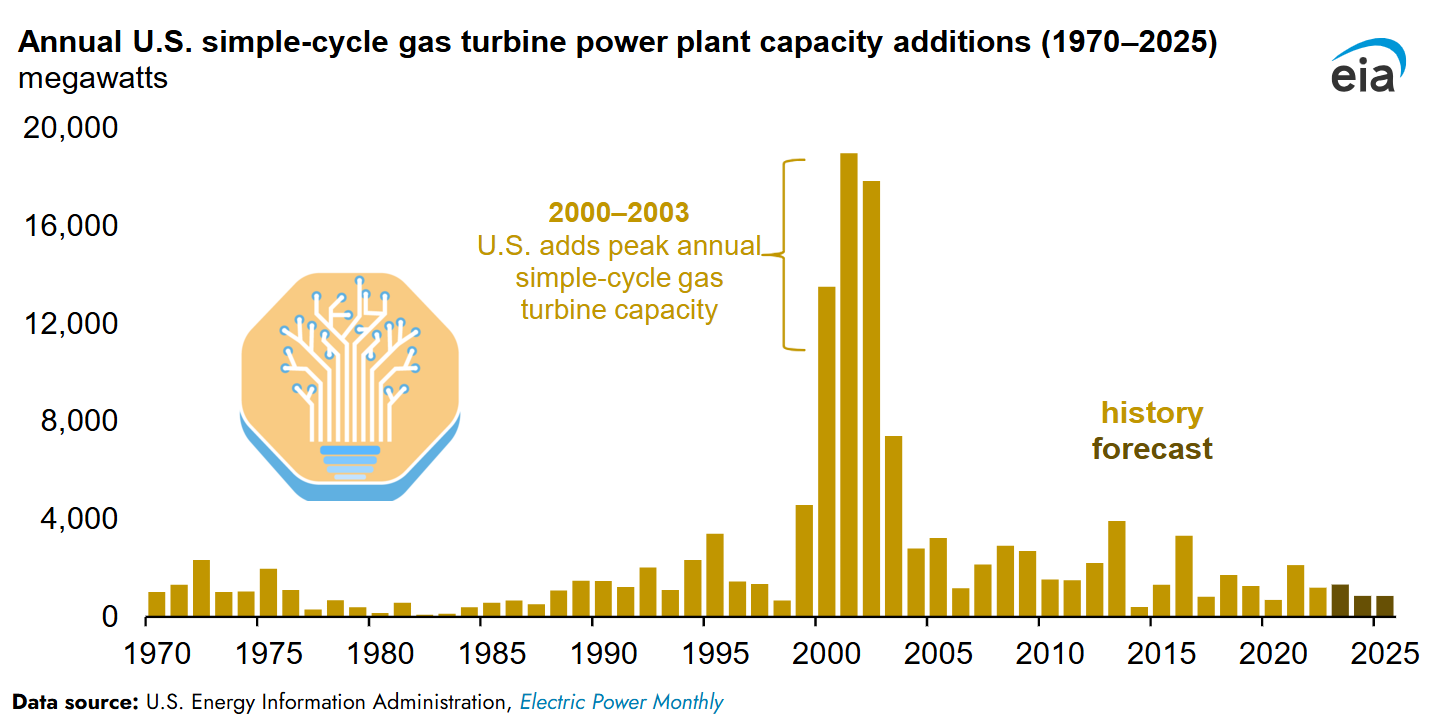

Of the major gas generation manufacturers, only Bloom Energy, Caterpillar, and newcomer Boom Supersonic have announced ambitious expansion plans. Bloom Energy has claimed they can reach 2 GW/year of production capacity by end of 2026, and Boom Supersonic plans to reach 2 GW/year by end of 2028. At first glance, few manufacturers appear fully “AGI-pilled” despite surging demand. Some of that hesitation reflects real manufacturing limits; much of it reflects PTSD from 30 years of boom-bust cycles in gas generation. Notably, the worst bottlenecks are in heavy-duty turbines. Aeros, IGTs, and RICE systems are less constrained.

The Two Boom-Bust Cycles of Gas Turbines

Since the mid-‘90s, the gas turbine industry has seen two boom-bust cycles rock the industry. The first boom, between 1997 and 2002, was driven by electric power deregulation in parts of the United States, which pulled in new companies as independent power producers, as well as (ironically enough) high expectations of electric demand growth coming from the dotcom bubble, as popularized by the Huber and Mills paper “The Internet Begins with Coal.” Large players like Calpine, Duke, Williams, and NRG placed block orders for turbines, sending GE Vernova (then GE Power) and Siemens Energy (then Siemens AG’s power segment) into lunar order volumes. GE shipped more than 60 GW of gas turbines in 2001; Siemens peaked at 20+ GW in 2002.

The crash came fast. The dot-com bubble burst, the Enron scandal shook the power trading business, and orders dried up, leaving GE and Siemens in a manufacturing winter for the next few years. The second “boom” in the gas turbine industry was less a boom than a stabilization of orders. Between 2006 and 2016, GE averaged about 20 GW/year of turbine shipments, and Siemens about 15 GW/year. Then, between 2017 and 2022, the bottom fell out on the market, with both GE and Siemens seeing production lows under 10 GW/year.

These two large companies have both institutional memory of the Y2K gas turbine boom and recent memory of generationally low sales. Notably, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries has largely escaped these boom-bust cycles. Until extremely recently, MHI has sold a fraction of the hardware of GE Vernova and Siemens Energy. It has only become part of a “Big Three” because the larger companies have shrunk to its sales volume and other players like Alstom Energy and Westinghouse have shuttered or been acquired. This may in part explain MHI’s interest in expansion, although its supposed doubling plan has not been corroborated in earnings calls.

Supply Chain Bottlenecks

However, within gas turbines, even a guarantee of high future demand may not push forward increased production, because of internal bottlenecks in the production and logistics of gas turbine cores.

Gas turbine blades and vanes are among the high watermarks for civilizational technological competence, requiring an insane quality of metallurgy and machining to manufacture properly.

Turbine blades and vanes are among the most demanding components modern industry makes. Manufacturing them requires extraordinary metallurgical and machining precision. As a result, Western production is concentrated in four firms:

Precision Castparts Corporation (PCC)

Howmet Aerospace

Consolidated Precision Products (CPP)

Doncasters

These companies supply not only industrial and electrical gas turbines but also civilian and military jet engines as well. All except CPP have vertically-integrated metals supply, but they are a fraction of the size of their customers, and thus much more vulnerable to market shocks. The second gas turbine bust coincided with a COVID-driven slump in aerospace orders, meaning these companies have recently been hit quite hard. An increase in demand would require these companies not only to hire more specialized staff, but also to reckon with their supply chain for materials like yttrium, rhenium, single-crystal nickel, and cobalt. More importantly, they are likely reluctant to make these investments because they stand to lose the most if they follow an AI bubble off a cliff.

Additionally, heavy-duty gas turbine production is constrained by logistics. The turbine cores alone are 300-500-ton systems that need specialized barges, rail cars, and truck trailers to transport. Even after permitting, heavy-duty gas turbines need 24-30 months to build, install, and test before they are ready to run. Aftermarket OEMs can build new plants around refurbished cores, but moving and integrating those cores remains a major challenge. These constraints are less severe for aeros and IGTs, which are small enough to ship on standard containers or conventional trailers.

New entrants to the rescue: from jets to ships?

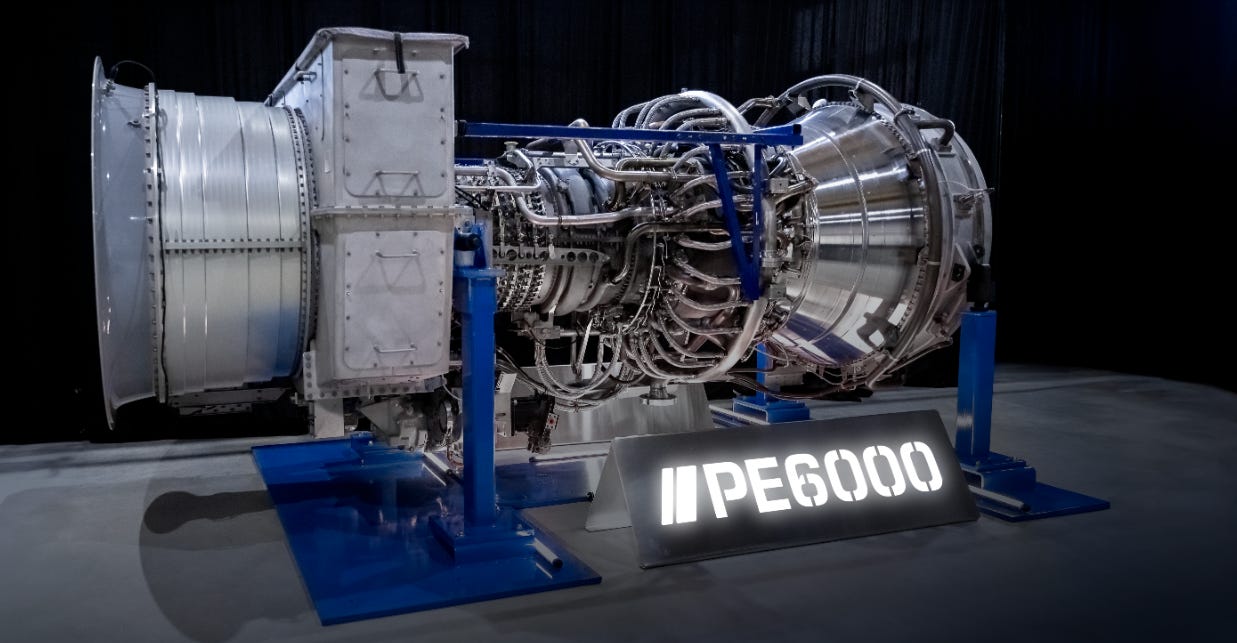

As often, in times of constraints, many smart firms are exploring solutions. ProEnergy was one of the first to come with innovations. Its PE6000 program retrofits CF6-80C2 engine cores from Boeing 747 and delivers operational aeroderivative gas turbines with near-identical specs and packaging to the GE Vernova LM6000.

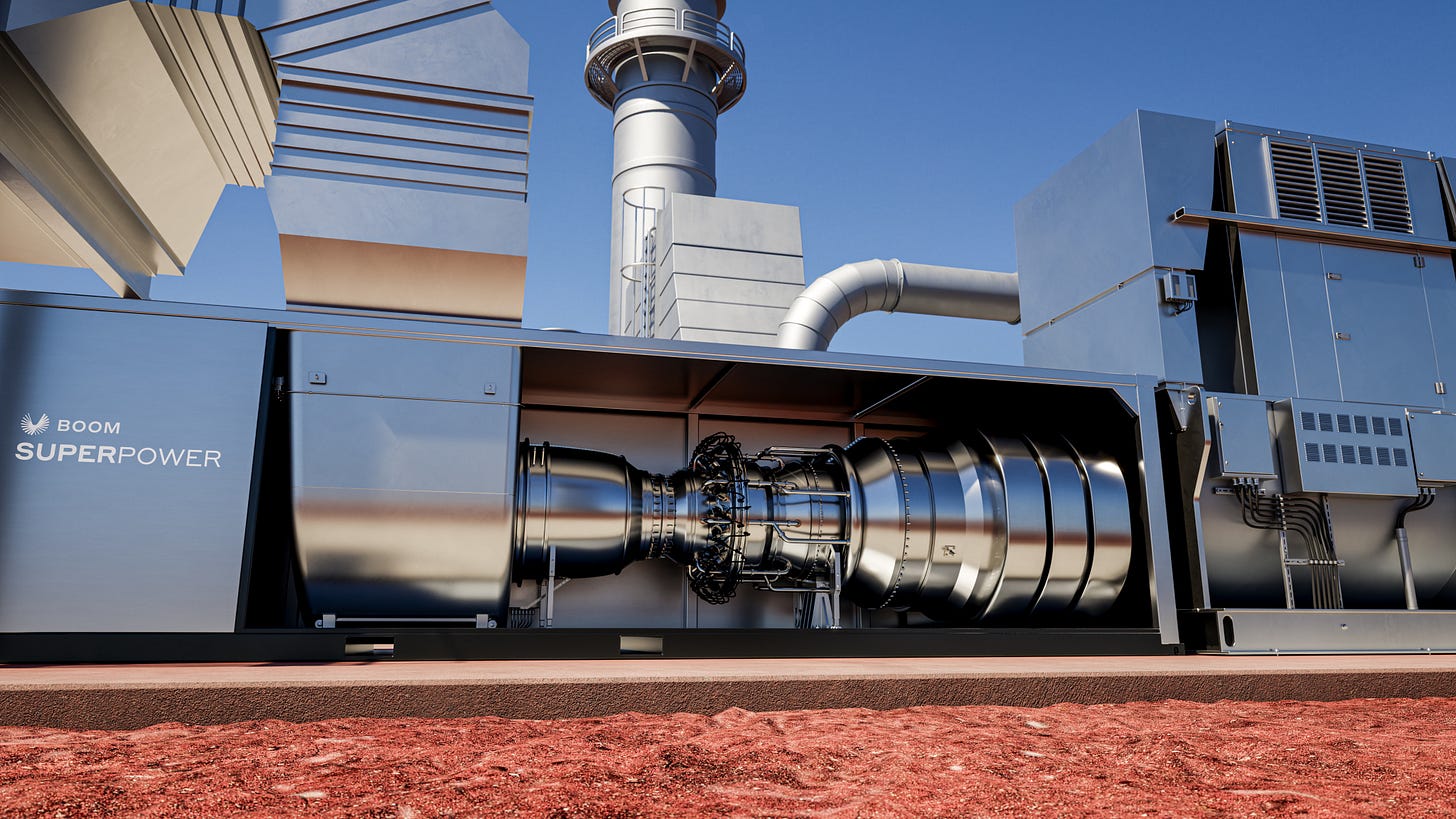

More recently, Boom Supersonic has announced the development of the Superpower aeroderivative gas turbine, based on their supersonic jet engine design. Its proposed form factor looks remarkably similar to the GE Vernova LM2500, and it operates on the same principle: a small jet engine that can fit in one shipping container (with auxiliary intake, controls, and exhaust equipment fitting in 1-2 more shipping containers). Testing for this engine is still underway, but preliminary advertised specs suggest the Superpower will produce 42 MW per unit, even at high ambient air temperatures.

The first 1.2 GW of production has already been booked for Crusoe, with a targeted 200 MW of production in 2027 and 1 GW in 2028, and 2 GW in 2029. The initial order price suggests a hardware cost of $1,000/kW, but that figure does not include balance of plant, shipping, or commissioning, and should not be directly compared against all-in cost figures. Boom Supersonic have vertically integrated production for blade and vane production, but rely on external vendors for metallurgy, which may remain a supply chain bottleneck.

We haven’t yet seen other firms jump on the retrofit wagon. However, medium-speed engines are largely manufactured by firms with a long experience building ship engines – such as Wärtsila. In fact, they are largely the same engines and can be manufactured in the same facility. When will we see old ship engines retrofitted to power datacenters?

Let’s now turn our attention to comparing the different solutions and manufacturers. We’ll also analyze the economics and TCO of onsite power generation, and compare it to the electric grid in the US.